A violent struggle is unfolding in Peru, and has been for four decades. Pitting military rulers against guerrilla fighters knowing as the “Shining Path,” the conflict destroyed dozens of rural villages, took 30,000 lives and displaced hundreds of thousands more in its bloodiest stages before the turn of the century. In the years since, scattered Shining Path fragments have remained active, occasionally reappearing to ambush soldiers. The contemporary Peru government has branded Shining Path a terrorist faction. As recently as 2017, journalists have walked the country’s landscapes and found, as reporter David Gonzalez wrote for the New York Times, “silent clues to a violent past”—tattered clothes, bones, mass graves.

I start off this way because that’s vital context for “Canción Sin Nombre” (“Song Without a Name”), a blunt-as-a-shotgun-blast new movie that walks a fine line between sociopolitical thriller and pure dystopian drama, occasionally stumbling onto either side of it. The film – gauzily photographed, as if we’re looking back on history with half-open eyes – is a piece of fact-informed fiction that attempts to examine a country’s conscience through the personal crises of two people maneuvering one of the most volatile moments in its history.

Peruvian director Melina León’s haunting feature debut begins just so, relaying newspaper headlines of a nation made weary from political unrest and economic turmoil (“Dynamite attacks, murder, rioting,” “water and electricity will continue being interrupted”) via the barely visible outline of a television screen. Flashing images show graffiti reading “Long live Leninism-Marxism-Maoism,” as well as masked militia and citizenry fleeing raging fires.

Whether the images are authentic or merely authentic recreation is besides the point; accompanying them is a disquieting background hum that sounds like something between lapping waves and the lonely static of post-oblivion society. Either way, despite Peru still being a place we can point to on a map, cataclysm feels inevitable for the figures in these images—the bureaucrats, the rebels, and the everyday men and women caught in between.

The images that follow portend cataclysm as well…or more specifically its aftermath. In 1988, a group of men and women commune in a small, bunker-like, candle-lit space, joyfully singing lyrics with biblical implication: “Herbal mountain, take me away/I want to die alone and far away.” Outside, a desolate landscape disappears into haziness. It could be a desert, a coastline shore or the top of a mountain reaching the clouds; it’s hard to be certain. The suggestively apocalyptic “Canción Sin Nombre” was shot by Inti Briones, whose impressively dour black-and-white images bring to mind Alfonso Cuarón’s explicit end-of-the-world drama “Children of Men.”

Another echo of “Children of Men” comes in the form of Georgina (Pamela Mendoza), a pregnant mother-to-be apparently alone in her anticipation. (Those who watched another Cuarón feature, “Roma,” may do a double-take; Mendoza looks uncannily like that film’s protagonist, played by the Mexican actress Yalitza Aparicio.) Fate finally seems to be lending its charitable hand to a woman in need of it when Georgina visits a clinic offering free help via radio advertisement. But there’s something suspicious about the timing of the ad.

The suspicions bear out. A subsequent return to the clinic as her baby is arriving leads to a harrowing unfolding of events; the newborn is taken to a nearby hospital, the nurses insisting she’s fine while unceremoniously shepherding Georgina out as she begs for answers through tears.

For what feels like an achingly long time, Briones’s camera lingers on the other side of a door as Georgina pounds away, crying for a daughter she hasn’t even had the chance to name. The picture slowly fades with the yells—a metaphorical bleeding-out of lost motherhood, and equally symbolic of a nation that’s lost its way.

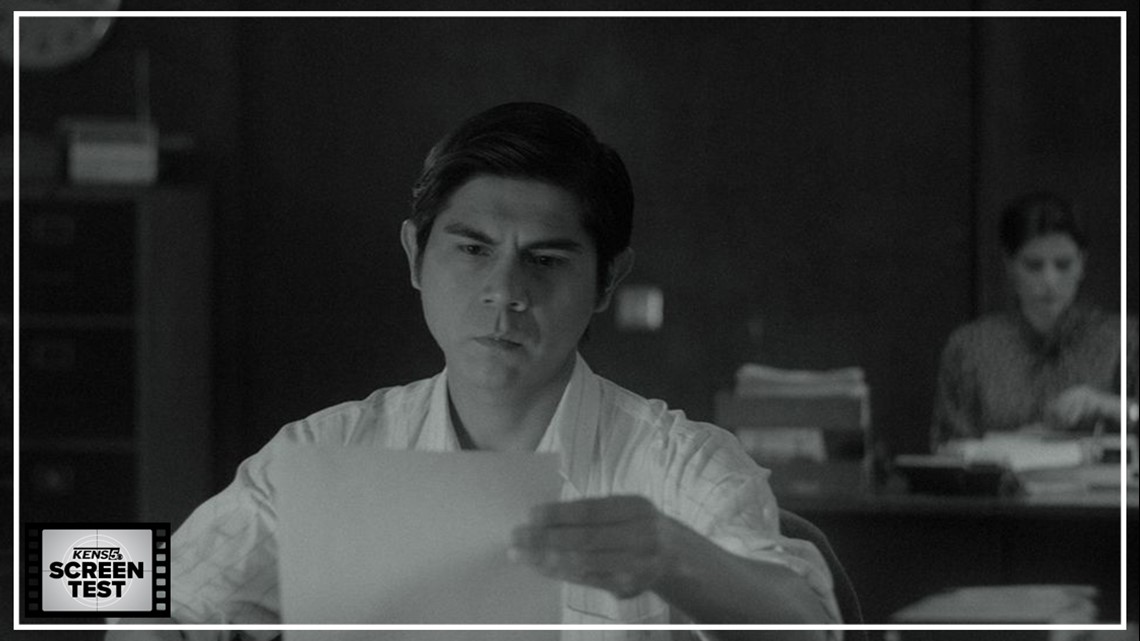

A stone-faced journalist, Pedro (Tommy Párraga), will soon agree to help Georgina look for answers, and it isn’t long before we sense they’re wriggling their way deeper and deeper into a conspiracy. At the same time, “Canción Sin Nombre” begins to more resoundingly resemble a striking portrait of a country at a crossroads than a compelling mystery of a mother and her missing child. Aesthetically, the movie is a triumph of despairing mood, with man-made structures and horizons that look and feel hypnotically infinite (watching “Canción Sin Nombre” made me miss theaters as much as anything I’ve seen in the last few months). What’s missing are engaging personalities to fill those spaces, which can lead to an awkward imbalance of tone, character and narrative.

Still, León, who co-wrote the screenplay with Michael White, has a veteran’s knack for conveying the gulfs of human decency separating authoritarian figures from those they preside over. Those macro insinuations at the heart of “Canción Sin Nombre” – the hints and symbols of institutional ambivalence rooted in recent history – are sometimes more than enough to distract from the suspicion that things begin to feel lackadaisical right when they should feel urgent for Pedro and Georgina. The film can be dazzling and dazzlingly patient in its grim suggestions of inevitable calamity; by comparison, it’s hard to find reason to be invested in Pedro and Georgina as characters when they’re defined by little more than their archetypical roles in the story. León and White’s overarching ideas often butt up against plot specificities.

That could be the movie’s point. A place can only truly be understood by those who inhabit it, and if Pedro and Georgina feel less like thoroughly sculpted characters, then they certainly function well as avatars of the lay people occupying the No Man’s Land of turbulent 1980s Peru—the third-party spectator uninterested in tossing a Molotov cocktail but whose babies can still be taken, whose relationships can be severed in the blink of a bruised eye. When “Canción Sin Nombre” is at its most soulful – including an emotional, exceptional final close-up to Georgina’s face amid her own internal reckoning – the question to ponder isn’t who claims victory between the aggressors. It’s whether or not those caught in the crossfire can retain their humanity.

“Canción Sin Nombre” is not rated. It will be available to watch via virtual cinema options on Friday.

Starring: Pamela Mendoza, Tommy Párraga, Lucio Rojas, Ruth Armas

Directed by Melina León

2020

OTHER SCREEN TEST REVEWS

- ‘She Dies Tomorrow’ Review: An unnerving study of primal reckoning

- 8 movies for the uncertain moment

- 'Radioactive' Review: An actively frustrating biopic

- ‘Amulet’ Review: A disturbing and daring horror tale shrouded in overfamiliarity

- ‘Carmilla’ Review: Gothic coming-of-age drama echoes the highs of modern horror without finding its own path

- ‘The Old Guard’ Review: Netflix’s comic book action-drama is a character study that shows what we’ve been missing

- ‘Greyhound’ Review: Tom Hanks stars in one-trick World War II drama honoring heroes of wartime past and cinematic present

- ‘Palm Springs’ Review: Andy Samberg and Cristin Milioti star in 2020’s most unexpected pandemic-era allegory

- ‘Desperados’ Review: Netflix’s latest will take you through the seven circles of cliché hell

- 'The Truth' Review: Catherine Deneuve shines in Hirokazu Kore-eda's drama about family, memory and narrative