If the history explored in Sam Pollard’s relatively straightforward yet revelatory “MLK/FBI” were in danger of emanating a certain obviousness about the United States’s infrastructural hypocrisies pertaining to its treatment of Black citizens, recent events render those concerns moot. Having premiered at September festivals with images from a summer of protest still fresh in viewers’ minds but the thought of a deadly siege at the nation’s governmental heart too dystopian for most to consider, this documentary takes on renewed significance as it prepares to wide-release on Friday—just nine days after a group of largely pro-Trump radicals stormed the U.S. Capitol, looting souvenirs, kicking back at political leaders’ desks and asserting fiery reality for anyone still denying that America can afford to delay its reckonings.

It’s impossible not to draw parallels between the headlines of 2021 and 1968 when a historian explains in “MLK/FBI” that federal authorities did nothing to bolster protection for Martin Luther King Jr. even as they were aware of growing threats against him. More damningly (and this is on the numbing effects of reality, not on Pollard), we may strain to find the necessary shock by the time we arrive there in the film, which takes a scholarly approach in separating collaboration in the name of unity and collaboration in the name of fragmentation. At its best, “MLK/FBI” sharply pierces the hardened context of today’s world, showing how that dichotomy has defined the country—and, in light of recent events, showing how it continues to. It may as well be called “MLK/USA.”

The origins of Pollard’s documentary are also anchored in recent events, specifically the 2019 news coverage of previously unreleased FBI documents detailing the bureau’s sly surveilling of King—cloak-and-dagger efforts that uncovered a private life of extramarital affairs and alleged complicity in an incident of sexual misconduct. Naturally, those initial news articles included the (heretofore unproven) allegation in their lede. Tellingly, “MLK/FBI” does not. Pollard’s curiosity and concerns don’t reside with unproven claims but with how that period’s bureaucratic machinery was motivated to submit such footnotes for the historical record—a record conveniently shaped mostly by white hands. By zooming out to scrutinize the state of J. Edgar Hoover’s predominantly white, male and conservative FBI – including how it sought to exploit King’s personal life to throttle his public mission – Pollard effectively creates the most fully-formed portrait of King’s evolving relationship to the country he strived tirelessly to improve. And it’s a portrait with plenty of gray shades.

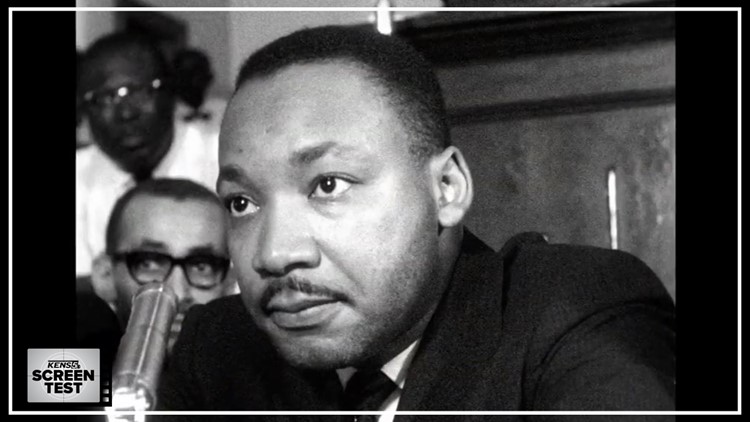

“MLK/FBI” focuses on the period late in King’s life when he was already fully in the public eye, starting with 1963’s March on Washington and the familiar images of a packed National Mall where his “I Have A Dream” speech would be delivered. It’s as natural a place to begin any documentary on the man, sure, but intentions are asserted as the film makes clear that this climactic moment – which saw MLK lead a crowd of 250,000 in demanding equal rights for Black Americans – was also the point when he was dubbed by the FBI “the most dangerous Negro in America.”

From here, “MLK/FBI” follows a coherently chronological structure in dissecting that tension. We learn about how it affected King’s relationships with political leaders. We learn about Hoover’s maneuvers to embellish public optics with a gilded image of his bureau as a superior moral authority. We likewise learn about how the FBI conflated a paranoia of communist agendas with Black activism, the repercussions reverberating throughout the Civil Rights Movement. All the while, the documentary deftly lays the brickwork connecting King’s ever-expanding influence with the FBI’s growing resilience to his efforts. It achieves its educational purposes, but you can count on it to also infuriate and challenge you.

And that, admittedly, is a fascinating achievement by “MLK/FBI,” considering how rarely – if at all – it strays outside an academic gaze, tonally speaking. Pollard’s hyperscholastic touch can sometimes border on the emotionally disorienting, such as when it jumps from King candidly discussing his family in a TV interview to an expert recounting the legalese of wiretapping. There isn’t a discernible shift in urgency when that transition arrives, but Pollard is too insightful a filmmaker not to think his audience would expect it. His lens is relaxed, for lack of a better word, in sections where other documentarians would dial up the score, make frantic the editing, emphasize the magnitude of the FBI so casually intruding on a man’s privacy so as to oppress an entire community. And the more this proactive documentary sits in your mind, the more you come to realize that isn’t a result of dispassionate endeavor, but of trusting the audience to link past with present.

The ostensible low-key energy that powers “MLK/FBI” – exacerbated by a noticeable decision not to show talking heads of historians and King’s closest aides on the screen until the end, even as we hear their voices – echoes the revealing and racist ease with which one of the United States’s most resourceful agencies targeted King. If our suspicions simmer as motivations are exposed, they explode when the documentary shows how they had a striking and tangible effect on influencing public opinion of white Americans. When the moment comes for the movie and its recruited historians to contemplate the allegation of rape eventually scribbled down by the FBI against King – an incident that, documents show, they weren’t keen on halting – we’re better equipped to consider the revelation on all fronts—moral, political, historical, foundational. It’s a smart move by Pollard, simultaneously catching us off guard and drawing us further into a documentary that can occasionally feel like it’s pigeonholing itself into routine narrative patterns.

“MLK/FBI” may be more striking as an accounting of past events than an innovative piece of filmmaking, but how the movie ultimately succeeds is borne out – as with other documentaries – in however the audience responds to it. To that end, it concludes by admitting that its purposes are somewhat unfinished; the FBI’s actual surveillance tapes won’t be publicly released until 2027. As if to emphasize our duty to examine history through a malleable lens, Pollard turns the camera on his previously unseen subjects to ask about their role in that examination. In that moment, we feel the weight of the question on our own shoulders. And that, in itself, is as telling about our responsibility to shoulder the weight as anything and everything we see in “MLK/FBI.”

"MLK/FBI" is not rated. It's available Friday in select theaters and also on VOD platforms.

Directed by Sam Pollard

2021

OTHER SCREEN TEST REVIEWS:

- ‘The Dig’ Review: Netflix’s scattershot archaeology drama is an expedition with little to discover

- ‘I Blame Society’ Review: Cheeky movie-within-a-movie experiment will keep you on your toes

- ‘The Reason I Jump’ Review: The experiences of a person with autism are explored in colorful, spirited, lightly profound new doc

- ‘News of the World’ Review: Tom Hanks travels across post-Civil War Texas in airy, occasionally intelligent Western

- ‘Soul’ Review: Pixar prioritizes concept over character in its most literal meaning-of-life tale yet

- The best movies of 2020