SAN ANTONIO — What’s in a story of vengeance? Cinema has not been wanting for potential answers over the last 20 years.

The contemporary revenge flick has come bearing samurai swords, long rifles, shaving blades, batarangs—and the subgenre has endured, even as the parameters have shifted to appeal to the dominant movie trends of our time. Ever consider how, underneath the CGI fury and interdimensional frenzy of “Avengers: Endgame,” it boils down to a spandexed revenge story orchestrated on behalf of a snapped-away galactic population?

Ok, so maybe that’s overstating things. Captain America might have journeyed through space and time to defeat Thanos once and for all, but his objective is completed with his humanity firmly intact. The same can’t be said for, say, Beatrix Kiddo, even as the scale of her own pursuit of vengeance is so comparatively intimate it could’ve been unfolding in some corner of the world far away from where Thanos was being extinguished. Yet we more readily identify “Kill Bill” as a revenge story than the “Avengers” saga. And that’s the thing: This subgenre is defined by its psychological stakes, its sense of primal undoing. Its most formidable examples aren’t categorized by how many foes get their comeuppance (though the extinction of the Crazy 88s is a key marker of the Bride’s sheer force of will), but how perilously close a character’s sense of self gets to the cliff’s edge that they don’t see for keeping their bloodthirsty eye on the prize.

Of course, this all depends on whatever you, dear reader, expect to get from a revenge story in which the drama is driven by violence or existential humiliation. It’s one of the great ironies of the movies that the most traditionally satisfying and mainstream-skewing of these tales are rarely also the most harrowing. To suggest, for instance, that you were satisfied by the soul-clenching culmination of Jeremy Saulnier’s “Blue Ruin” might get a raised eyebrow from someone who went into that movie not expecting they'd have to keep their head above its murkish gray waters for 90 minutes. On the flip side of the prestige/indie coin, surely it’s been long enough that we can admit any collective awe at Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s emotionally vacant “The Revanant” was fueled by Leonard DiCaprio’s long-overdue Oscar campaign, and not by any striking ruminations about the cost of vengeance that simply weren’t there in the first place.

The blind spot is apparent in our box-office hits, too, including the most recent ones. Broadly speaking, conversation about the latest “John Wick” entry starts and very nearly ends by focusing on the ambition of the action and not what it reveals about Keanu’s circular pursuit of vengeance. “Oppenheimer” doesn’t fit the revenge-movie mold, but the fact that audiences aren’t entirely willing to grapple with the core subjectivity of a man who paved the way for the most devastating act in human history (an observation the LA Times' Justin Chang explored fully and boldly) is an indication of just how black and white most moviegoers expect the stories they see on the big screen to be. Then again: If the continuing success of Barbenheimer proves anything, it’s that audience are as compelled to return to cinemas as any point since the heights of the COVID-19 pandemic, curious even about the movies they may have had certain expectations for before finding something else entirely.

It’s into this moviegoing ecosystem that the arthouse film distributor Neon has decided to unleash – in a manner not unlike the dastardly destiny the movie’s protagonist marches toward – a restored version of the 2003 South Korean thriller “Oldboy,” a mysterious and stylistically maniacal piece of revenge cinema in which audiences only think they see the line between black and white before realizing it’s been behind them the whole time. It comes from director Park Chan-wook, the master visual orchestrator who would go on to make “Stoker,” “The Handmaiden,” last year’s “Decision to Leave," works whose twistier narratives deepened the thematic intensity of his already-vivid compositions.

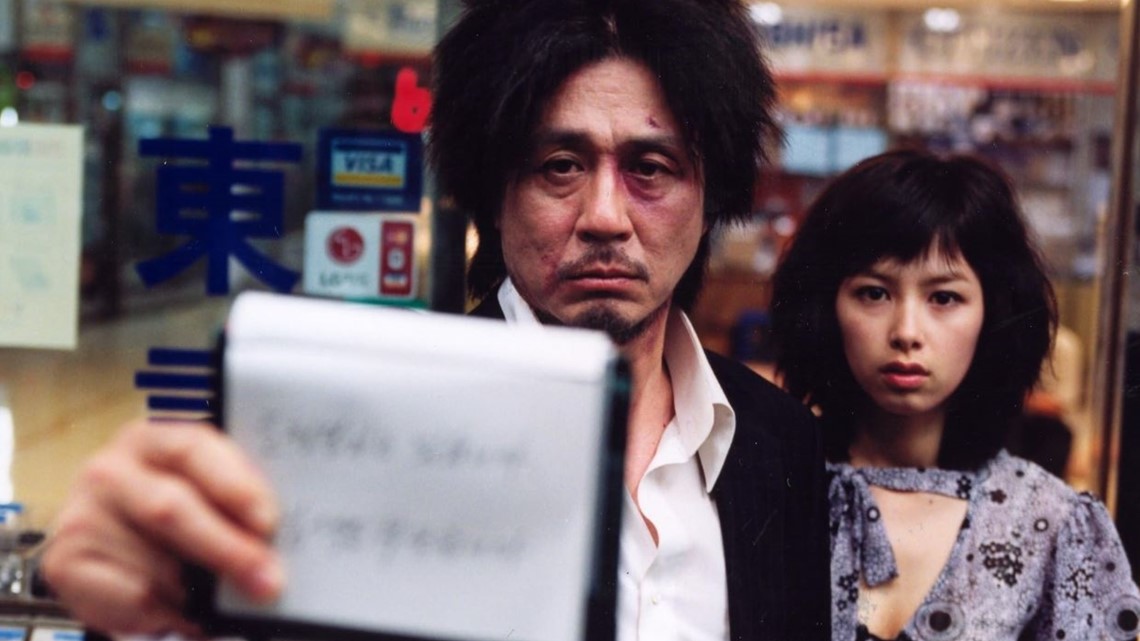

Still, it isn’t entirely accurate to call “Oldboy’s” own narrative straightforward. Beginning with the abrupt and inexplicable imprisonment of Dae-su Oh (Choi Min-Sik) after a night of heavy drinking, Park ensnares us in a black hole of potential implication that steadily pulls us toward its all-consumer center of gravity once it becomes clear that 15 years have gone by without Dae-su so much as leaving his living room of a cell, let alone given any explanation for it. A TV set becomes his only window into the world, and the first of the movie’s many enduring images – that of a wild-haired Dae-su staring into the camera while wearing the freakish grin of a man dehumanized – lays bare the kind of broad-strokes story this will inevitably become, even as there’s no telling which turns it will take.

Once Dae-su is finally released, he doesn’t need to state his mission of revenge for us. We feel it in our bones. We want it for him, too, if only because we are also owed some kind of explanation after a disorienting prologue. There’s a reason we feel a certain sympathy during the horrific sequence that finds him slurping up and chowing down on a writhing octopus, as if he was invigorating himself with a liveliness the previous 15 years have deprived him of.

It only gets more visceral from there in the middle and most fiendish installment of Park’s so-called Vengeance Trilogy – sandwiched between “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” and “Lady Vengeance” – which examines the implications of revenge in various forms, from the carefully calculated to the perilously feral. The key uniting element is violence, and the first thing that “Oldboy” first-timers should know is that it carries a reputation for having the strongest sting despite perhaps the least amount of onscreen butchering, slicing or electrocuting of the Vengeance Trilogy (a fact that’s easy to forget, given the standout and oft-imitated sequence that sees Dae-su fighting his way through a mob of enemies in a hallway, armed with nothing but a hammer).

Asked years ago about whether the trademark violence of his films come from a personal place, Park said: “I’m just the opposite.” That checks out: “Oldboy” has a quality of curiosity about it, of Park examining the logical ends of where Dae-su’s vengeance will take him. (Spoiler: extreme ones.) He’s a director comfortable with saying he wants his audiences to be tired when the credits hit, for the films “to be felt physically, not just emotionally.” By the time Dae-su has unraveled the mystery of his imprisonment, his mission has achieved a renewed urgency—and reached a higher peak from which to plummet from when the gut-churching climactic twist is revealed, culminating in one of the most unforgettable displays of hopeless desperation you’re likely to ever see. Age hasn’t diminished “Oldboy’s” impact; it’s re-emphasized it.

That’s what makes it so devilishly funny and strangely appropriate that “Oldboy” returns to cinemas at this point in time to be experienced by a reinvigorated moviegoing public. Audiences may be gung-ho after being challenged by the concepts of “Barbie” and the structure of “Oppenheimer,” but no amount of surprise rock ballads or breathtaking bomb test sequences can prepare them for the more primal shocks that await in “Oldboy,” a movie whose raw power and unsparing perversity only glows all the stronger against the comparatively sanitized experiences of almost anything else American filmmakers have released since then (“Oldboy” was ferocious enough to kick the Korean New Wave into another gear before it reached its peak with “Parasite’s” Best Picture win at the 2020 Academy Awards). The 20th-anniversary rerelease of this revenge movie practically represents the subgenre getting its own revenge, restoring its depraved honor in a wider canon.

You might even be able to glimpse the spots where “Oldboy” has influenced movies that would come out in following years; one sequence finds Dae-su literally chasing himself through stairwells, memories and time, and it’s hard not to think about Christopher Nolan. Yet even now – 20 years later, and heralding a scuzzy reputation as a gateway to the marvels of international cinema despite being near-impossible to find on any streaming platforms – it’s hard to think of any movie that's come out since (outside Park’s own oeuvre, at least) that so directly challenges audience’s expectations about revenge stories, and the value we expect them to carry as a vehicle of entertainment versus being a mirror into our own thirst for spectacle.

The very thrill of watching “Oldboy” — particularly for those who already have — involves not only looking at the screen but at looking away from it, at the faces of those around you. Movies can’t be this daring these days; movies so rarely are, especially when it’s Hollywood making them. I revisited “Oldboy” on a TV screen in my living room, and even in those confines I could appreciate — and, sure, imagine with wicked glee — how certain sequences will play out in theaters.The iconic side-scrolling fight sequence will elicit cheers in the age of “John Wick,” but those very same audience members might find themselves compulsively tightening up in the last 20 minutes, wondering if laughing or screaming is the appropriate reaction.

“I’ve now become a monster,” Dae-su says when blood is finally drawn by his barbed-wire fate. And we now, once again and for some for the first time, have a new benchmark for what we really talk about when we talk about cinematic stories of vengeance—if not for what the movie says about consequences of revenge, then for the assurance that you will feel it in a place where thrillers rarely reach.

"Oldboy" is now in San Antonio theaters. It's rated R for strong violence, including scenes of torture, sexuality and perverse language. Runtime: 2 hours.

Starring Choi Min-sik, Yoo Ji-tae, Kang Hye-jeong, Kim Byeong-Ok

Directed by Park Chan-wook; adapted by Park, Joon-hyung Lim and Jo-yun Hwang from the manga by Garon Tsuchiya and Nobuaki Minegishi