[[Note: When "The Father" releases in the U.S., it will largely be at indoor movie theaters during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. While the purpose of this review goes deeper than binary recommendation to discuss the film's merits as an artistic work in context of its time, we encourage our readers to continue exercising the latest safety guidelines from health authorities and consider them if and when you may decide to visit the cinema to watch this movie.]]

All but a few of the 97 minutes of Florian Zeller’s impressively constructed “The Father” unfold in one location — the intestines of an English apartment — yet Zeller’s debut decidedly isn’t in the lineage of single-location films eager to emphasize cramped geographies. This isn’t, say, the claustrophobic juror’s room of “12 Angry Men,” and certainly not the vehicular confines of “Locke.” An office, a bedroom, a kitchen and a hallway all somehow connect to a central living room like arteries to a heart, but that’s where our confidence likely ends if we were to draw up a rudimentary blueprint of the place.

But while watching “The Father,” we also increasingly lose confidence that characters who exit certain rooms will ever return—or, if they do, will they even look the same? Will it still be the morning when we cross into another room, or will the sun have gone? Will mere seconds have passed or months, possibly even years? A disorder of aesthetic continuity and spatial assurance abounds, deftly matching the stakes of the plot, which revolves not around being trapped in a shapeshifting haunted house (although Zeller certainly tip-toes up to the territory of cerebral horror), but in the labyrinthian reality of its titular patriarch, Anthony Hopkins’s Anthony. In his psyche we find the walls of reality continuously retracting and swelling – at a beat that refuses to be nailed down – due to his suffering from an ambiguous condition that the screenplay (written by Zeller and Christopher Hampton) duly alludes to being a symptom of old age. Yes, “The Father” largely takes place in one location, but that’s a slippery trait to prescribe to it. Because the more we, examining things through Anthony’s unreliable perspective, feel our way through these rooms and halls, the more likely it is we’ll lose our way entirely. And it’s in that sense that “The Father,” a riveting, perplexing work that doesn’t fit the contours of conventional horror, nonetheless becomes about a person caught in one of the most horrific and horrifically realistic situations we can imagine. It frays our nerves before throttling the heart.

It’s a testament to the synchronous efforts of Zeller’s various technical collaborators – editor Yorgos Lamprinos, production designer Peter Francis, cinematographer Ben Smithard among them – that our navigating the narrative’s sickness-hastened illogic becomes so asynchronous an endeavor, to the point where any reveal is possible as the camera slowly peers around the corner. And so “The Father” fashions itself into a kind of unorthodox ghost story, one whose specters are colliding memories that float in and out with such frankness and fluidity that we have no choice but to stay on our toes for when the next one arrives.

Our perspective, and that of Anthony’s, finds itself on shaky ground from the jump. The film begins with the day’s visit from his daughter, Anne (Olivia Colman, excellent in her first major film role since snagging an Oscar for “The Favourite”), who places herself between a rock and a hard place by telling Anthony she’s readying to leave for Paris to be with a man she’s recently fallen in love with. He accuses her of abandoning him; she says it’s what’s best for her now, she can still visit on weekends, and besides, doesn’t he think he’d be better off in an assisted living home? Anthony will have none of it—he’s oblivious to having become a burden and insists he can take care of himself.

It doesn’t take long for our faith in those words to waver. Anne has suddenly disappeared, and there’s a man in Anthony’s living room who he doesn’t recognize. He calls himself Paul, and says he’s Anne’s husband...and has been for 10 years. When Anne does return, it isn’t Colman filling her shoes but Olivia Williams, who bears just enough of an uncanny resemblance to the former that Anthony’s confusion reverberates onto us. In this moment, we realize the tricks Zeller has up his sleeve, though we’d be remiss not to wonder how long that sleeve is, how many forms these tricks can take. “He is capable of reacting unexpectedly,” Anne says of Anthony to a prospective caretaker, a line delivered with equal amounts of obviousness and a blossoming of storytelling potential, while also hinting at the implications of Anne’s being unable to totally understand Anthony’s plight. It’s to Zeller’s credit that the sentiment remains as true for him as it does for his protagonist.

This is a confident cinematic debut for the French writer-director, who takes full advantage of familiarity with the material—he’s adapting his own stage play, which premiered in 2014 to high praise. From the way it captures our attention through dialogue and practical dramatic flourishes, “The Father’s” theatrical roots are readily apparent to anyone who hasn’t seen the stage production (myself included). But transitioning the story to a cinematic experience, I imagine, has yielded new possibilities for Zeller in terms of atmosphere, of depths of mood and stylistic virtuosity that more than makes up for what may have been lost in that transition between mediums; by enveloping us in Anthony’s malleable state of mind, Zeller provides an engine for the drama while taking full advantage of cinema’s ability to flex perspective and our sense of time.

It’s perhaps not a coincidence, then, that we’re initially introduced to a confused Anthony desperately searching for his misplaced watch before the film eventually depicts much more consequential results of splintered memory. Here is a simple premise explored by a screenplay that becomes knotted, tangled and double-looped on itself, creating an intentionally messy tangle of assumptions and revelations that finds pathos in the very human frustrations that spark when those assumptions and revelations collide. It isn’t unlike Charlie Kauffman’s recent “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” – another storytelling enigma in which we never quite trust what we’re seeing – but where that movie demands debate, “The Father” is crystal-clear.

Key to its success is how the betrayals of Anthony’s mind warp his relationships with others. What irks him isn’t so much that he can’t find his watch, for example, so much as he’s sure – absolutely sure – that his caretaker stole it. Bodily degradation gives way to interpersonal deterioration, most memorably observed in the dynamic between he and Anne, not in the least because Colman and Hopkins are Zeller’s greatest assets. The two actors are mighty effective screen partners, crafting a wholly believable relationship that’s taken a melancholy turn where thorns can sprout at any second; the performances are helpful in a movie whose obtuse structure occasionally threatens to trivialize its subject matter, elevating the proceedings above mere aesthetic exercise. Colman is especially excellent when Anne feigns agreeability with her father while teasing just enough of a different internal state—a different kind of confusion, a different kind of turmoil.

Her performance adds a different dimension as well: that of internal motivations that may or may not exist, but which Anthony calls out when accusing Anne of wanting him at a nursing home simply to take his apartment for herself. Who can we trust when there’s so little about Anthony’s real-time point of view to be trusted? The mark of Colman’s triumph is we feel for Anne as much as for Anthony, and as those bonds between audience and character are tested, “The Father” reveals itself as toying with our loyalties as well as our perspective. The movie plays its subjectivities like a guitar, each pluck of a string further putting into question not just external logic, but emotional intention.

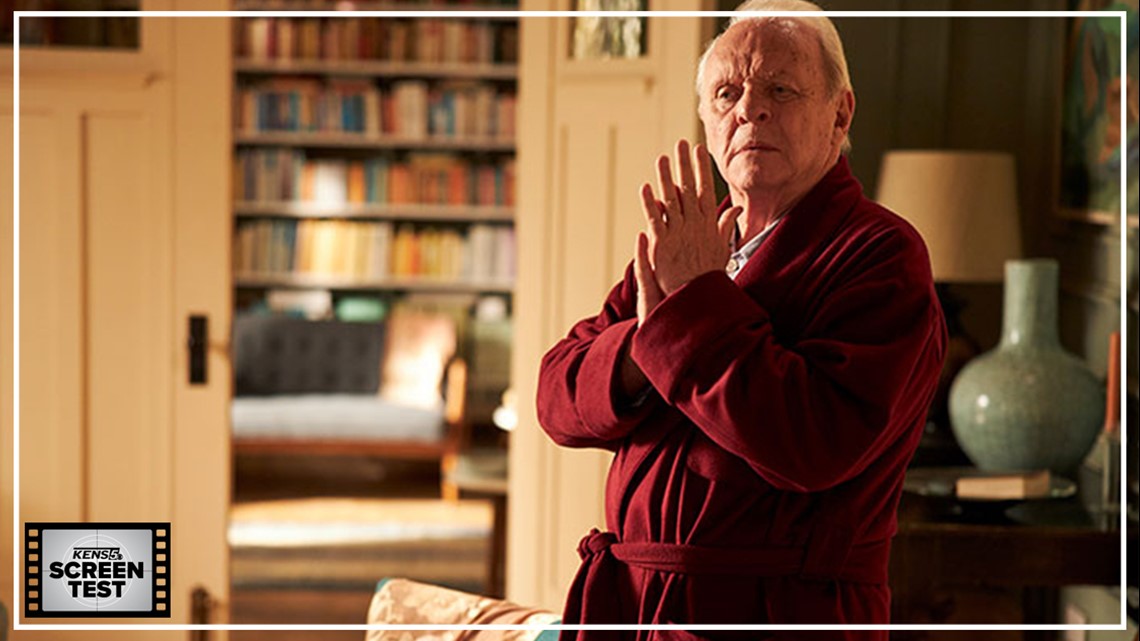

That’s where the fruits of Hopkins’s casting fully come to bear. Aside from drawing one of the finest performances from one of our finest actors (don’t be surprised when he’s nominated for an Oscar), “The Father” understands that Hopkins’s trademark quality is confidence. But confidence for Anthony – a character who always thinks himself one step ahead only to find he’s two steps behind – is faltered at every turn, and Hopkins navigates the self-subversion with a livewire performance that thrills as much as it devastates. Ironically, the 83-year-old actor is confident as all-hell here, often physically defying his age before swiftly embodying a gravitas worthy of it.

In the hours after watching “The Father,” I found myself pondering the movie’s formalism as much, if not more, as I was tugged by the movie’s emotions. But the two still compliment each other in its best sequences, including the film’s final minutes, when true north is nowhere to be found in Anthony’s Rubik’s-Cube reality. Hopkins rises to the moment with some of the most heartbreaking moments he’s given to the screen, a finale to a performance in which he’s constantly trying to convince not just Anne or us of his mental capabilities, but himself as well. By the end, the only thing we’ve witnessed in “The Father” that we’re sure is genuine is Anthony’s sadness when that effort runs out.

"The Father" is rated PG-13 for some strong language, and thematic material. It's opening in select San Antonio theaters Thursday, and will be available to rent on digital platforms March 26.

Starring: Anthony Hopkins, Olivia Colman, Mark Gatiss, Imogen Poots

Directed by Florian Zeller

2021

MORE REVIEWS

- 'Boogie' Review: An Asian-American hoopster looks for his big shot in Eddie Huang's new drama

- ‘Land’ Review: Robin Wright the director lets down Robin Wright the actor

- ‘Raya and the Last Dragon’ Review: Disney Animation's latest is a dazzling, thoughtful adventure

- 'Lucky' Review: New Shudder offering constructs a gaslighting prison from modest but piercing genre-subversion

- ‘Cherry’ Review: The Russo Bros. trade MCU superheroism for gritty superficiality

- ‘Nomadland’ Review: Frances McDormand ventures west in a lament and tender celebration of America’s final frontiers

- ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’ Review: True-life treachery within the Black Panthers’ ranks