SAN ANTONIO — Six and a half years after arriving in San Antonio from New York – a span of time that saw him contending with a pandemic while working to spotlight artists from underrepresented communities – Richard Aste is sketching out the next steps of his journey, so to speak.

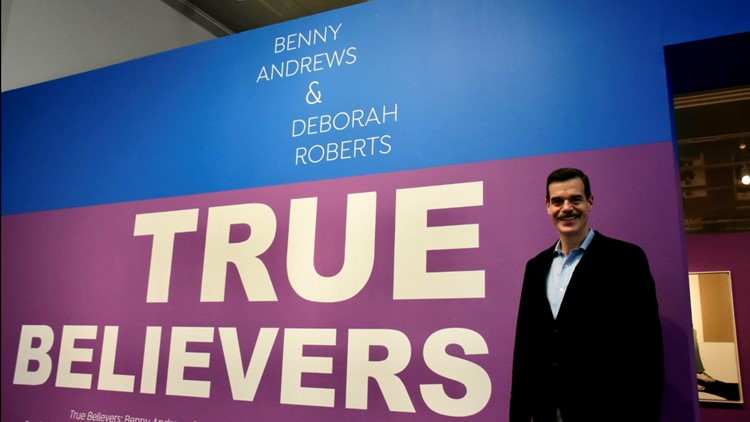

The McNay director and CEO announced last summer that he was moving on to Los Angeles, where he plans to transition into mentoring leaders and coaching executives. The museum last month announced his successor will be taking over on Feb. 13, about a week after two exhibits defining at least part of Aste's tenure – "True Believers" and "Blurring Borders," exploring the perspectives of Black and immigrant Americans, respectively – close down.

Speaking with KENS 5 at The Studio, a new interactive space where younger visitors can design their own exhibitions, Aste, the McNay's third director and its first Hispanic CEO, discussed his experiencing leading the museum and the challenges facing art institutions today.

(The following conversation has been edited for clarity.)

KENS: As we sit here today, "True Believers" and "Blurring Borders" are still going on; two shows that show different cultural and sociopolitical perspectives through the experiences of their artists. As a McNay leader who has championed inclusive programming in your time here, how has the mission of the modern art museum evolved since your arrival?

Richard Aste: Ever since the 19th century, art museums had a reputation of being high temples for elite arts. Community wasn't front and center; it was more of an aspirational destination for those of us in an art museum community to work our way up to being worthy of engaging with art.

Long before I joined in 2016, that was starting to shift. That temple on the hill was actually coming down to the community, and what I love about what we've done these last six and a half years, is commingle the McNay with the community. Take it from a temple of high art on a hill, and we are literally on a hill, into San Antonio metaphorically by breaking down barriers to the experience of the museum.

What are some unexpected ways that you found your own priorities evolving here, and what spurred those changes?

I think of something I experienced, which was COVID. That was the No. 1 unexpected event that fell in the second half of my six and a half years. Thankfully by then we had been working as a team so well, and when I say team it includes the staff as well as the board and the community all working in tandem on thinking about being more socially conscious in our work, and also never losing sight of the fact that we are a destination for artistic excellence.

So when when the shifting that happened as a result of COVID and the murder of George Floyd and the justifiable calls for for change, the McNay was already there. So it was unexpected externally, but internally it was very expected; we were already thinking in an even more inclusive direction. So we didn't feel the turbulence of change as much. We just stayed the course, and it was such a luxury to be able to stay the course when so many of my colleagues across the country were playing catch-up to where they should have been.

One of the biggest projects you oversaw in your tenure here was the $6 million landscape renovation. That project made the museum more open, more welcoming—that seemed to be a big part of the mission. How important is inclusivity not just when it comes to the artists you spotlight, but to patrons?

It's the most important part of my job as a director. I've always defined success here since day one as the inside of the McNay looking like the outside of the Mcnay. Which means that the more and more we start reflecting and including our community here, on these 25 acres, the more responsible we're being with this gift from our founder that goes back to 1950. She was committed, Marion Koogler McNay, to this community that adopted her and made her feel like at home, and we want to continue that legacy. So we continue to track how much we're looking like San Antonio.

One of the highlights of my time here was, as you mentioned, the physical opening up with the campus. That came in 2021, and we did a lot of work during COVID to open up the campus. That came from the vision of the late board chairman Tom Frost. Tom and the board and my predecessor, Bill Chiego, at the time realized that that was hurting us. Our face was hurting us. We were reading from the outside as an exclusive private institution. There was confusion even driving by before opening up the campus that we were still a private house or a country club, some thought we were cemetery. In our mission, which is our roadmap, there is nothing that references exclusivity. It's the exact opposite.

When I got here, the mission was already in place two years before in 2014. I loved every one of those 17 words (of the mission statement), and I just kicked into turbo as I joined and brought each of those 17 words to life.

And it extends – because of space we're in, The Studio – to cultivating appreciation in younger visitors as well, right?

Yes, you're never too young to start experiencing artistic excellence. When we say community impact here through artistic excellence, it's our entire community from the very youngest age. What breaks my heart is that there are still museums, art museums in this country, that aren't open to kids until they're age 10. That is beyond the formative years. Those kids and those museums have a different relationship with art and with art museums as a result of being excluded from them early on.

For us, we have Toddler Art Play, we have programs from cradle all the way through retirement. And those kids, who I'm so grateful to see on this campus, really grateful to their parents, will forever have a positive relationship with a place like this and know early on, if their parents brought them here, that this is for them. This is a place for them.

There was also a small bit of drama last February when, as was covered in the Express-News, the McNay rejected a work that had been deemed too sexually explicit to be on display. Some other artists pulled their own works in protest. How do modern art museums determine where the line is of too vulgar or too explicit, especially when the parameters of modern art seem to constantly be in flux?

I think going forward what we learned from that experience was that we can never overcommunicate enough our perspective and artists' perspectives, and really honor common ground. Where can we meet in the middle to open minds and open hearts? Because only when we meet in the middle and are aligned in the final product can we make a difference, can we make an impact.

What we learned there is that when we collaborate with our community, we have to be very, very transparent about our objectives in that collaboration. And we want to hear from our collaborators the same thing, what are your wants, what are your needs? And then together, and we're in the right city for it, we'll find that common ground.

When I moved to San Antonio, someone told me from New York City moving here that I'm about to enter a community where a Republican and a Democrat can be best friends. I found that to be very much the case. And in fact, now moving on to Los Angeles, I'm using in my mind San Antonio as a model of common-ground building. I think that exhibition was an opportunity for us to learn how to be better at building that common ground with our collaborators, including artists.

There's such a robust network of local galleries and artists, and how much they support and uplift each other. What has been your biggest takeaway or discovery about San Antonio's artistic community?

The passion that's here, and the purpose and the talents. It's really remarkable. One of the first artists I met when I moved here was Vincent Valdez, who's now in Houston but was born and raised here, and (his) early training happened here. What I learned from Vincent about the community of artists is that they are just as committed to social justice and community impact as they are artistic excellence. And it's not a zero-sum game. It's not one at the expense of the other. There is room for both and there are very gifted artists, especially here in San Antonio, that are flexing both simultaneously. That's a special product when you can pull that off. I always say, "Come to the McNay and experience art through beauty, and leave with enlightenment." These artists, in particular Vincent, really catch your eye through the beauty of their talent. Then, as you're communing with these works, they layer in the social message. I think that's been really effective here with our community, in that ultimate goal of opening minds and opening hearts.

It's one thing for there to be that tight-knit community of artists supporting each other. It's I imagine another challenge to motivate San Antonio's residents at large to seek those exhibits out. In your time here, what has been the McNay's role in cultivating that relationship?

What's great is that artists here are collaborators throughout the museum experience, and they become our ambassadors in communicating the message of the museum, across San Antonio. We for years, even before I joined, had a project called "Artists Looking at Art" in which we engaged artists from the community to respond to the collection. We just took that to the next level in the space we're in right now called The Studio, in which we invite artists in residence twice a year to activate our former museum's store, 1,000 square feet front and center in the lobby, so that when you do come here you know that we're artist-first. And we're artist-driven. We help artists help us unpack the McNay experience.

So we give them a platform, but they in return help us understand the 23,000 objects that we're custodians of, and they, because of their experience in working with us, will then go to the community and share not only their exhibition, but also the other exhibitions that are happening here simultaneously, which on average are 12 to 14 a year. There's a lot going on here and we could all be better at communicating it to San Antonio, so we're just very grateful that artists become part of our family and also go out and become part of that communication.

Richard Aste prepares to depart as McNay director

There was also obviously, as you alluded to, a pandemic which occupied a good chunk of of your time here. The McNay was closed for a few months in early 2020 before starting a phased reopening. What did you learn or observe in that time about the role local museums play in their communities in times of deep uncertainty?

What I learned is that there was great concern about the unknown, and we were in completely uncharted waters. But what I also learned was that we're very fortunate to have a board of trustees that put the staff first. The very first thing they said was that we are staying together as a family, as a museum family. And despite the turbulence that's coming – and we all knew that it was going to be bigger than what we initially thought – this was a stable place for our staff and also for our community, and that they can continue to count on the McNay when we do come out of this. That we have been an institution of great stability since we opened in 1954. And the pandemic is no match for this mighty place. So I think it gave us, at least in San Antonio, that peace of mind that, yes, we will all change as a result of the pandemic, but some things will still be part of what we can count on in the community.

What are the biggest short-term and long-term challenges facing the McNay and other modern art museums here and abroad?

The biggest challenge that I find is that culture is being more broadly defined today. So for culture vultures, and people who identify as culture seekers, they would traditionally come to a museum and we could rely on on that visitorship. Today, those who seek a cultural experience define it beyond an art museum experience or a musical and performing arts experience. They also include food trucks, and Coachella, and food and wine festivals, and Netflix series. These are all cultural events, watching "Bridgerton" and "Downton Abbey."

So we compete not only with other cultural institutions today; we compete with the couch. And so we know that our guests' time is precious, their free time is very precious. So how do we stay relevant? How do we continue to meet them where they are, as they continue to change their wants and needs, and really broaden their wants and needs? What we've done really well here is lean into our core value of innovation and define art on this campus beyond painting and sculpture. In these last six years, we've taken that definition to include classic American cars from the '50s and '60s, fashion from the 1990s, immersive experiences from Japan and the UK.

We continue to think, "What's next here?" Because we are a museum, the first modern art museum in Texas, that constantly reinvents itself. So it is a challenge (determining) what's the next reinvention. But the McNay is up for it, because we all universally think of this place as the definition of innovation.

I'm also reminded of your current exhibit on the "Wicked" costumes when it comes to finding opportunities for cross-pollination of different cultures.

We have the good fortune here of defining culture broadly on our campus based on even our existing permanent collection. Most art museums will define art through painting, sculpture and works on paper. We also have broken beyond that to include the theatre arts, thanks to the Robert Tobin gift and our great Tobin theatre arts collection, which is half of our 23,000 objects. Currently culled just from mostly the permanent collection, we have an exhibition called "Something Wicked: The Art of Susan Hilferty" that celebrates the art of theater and the art of the stage, and helps visitors see that beauty is all around them in many forms. That's our job.

>TRENDING ON KENS 5 YOUTUBE: