What has San Antonio lost with the dissolution of its full-time symphony? ‘A cultural aquifer’

Frustration lingers a month after the 83-year-old organization's board announced bankruptcy, but those most directly affected are also hopeful.

Even before San Antonio Symphony executives announced bankruptcy a month ago this week, Andrew Sutton held a front-row seat to how far the ripple effects might go once the curtain came down on the organization after 83 years.

As orchestra director at Steele High School, Sutton said he’d talked with his students about the state of the symphony and why its performers embarked on a months-long strike. Some of those young musicians, having previously considered turning an extracurricular into a career, suddenly found themselves learning about the importance of having a plan B.

“They're like, 'Maybe I should not do this full-time. Maybe I should just make this a hobby,’” Sutton said. “And we're talking some talented musicians that could potentially go on and do the full music conservatory track if they wanted to.”

Some years ago, San Antonio native Samber Saenz found herself in that position, when an everyday field trip to the symphony unexpectedly sparked a new passion.

A first-grader at the time, Saenz was wearing a new dress and shoes bought by her mom.

“She said it was important to look nice for special events like the ballet and the symphony,” Saenz recalled. “I didn’t know what I was in for until I was there… I felt like there was nothing else happening except the music I was experiencing.”

The concert inspired her to join choir and other competitive musical activities. Later, she would take up the violin and even meet her future husband in her middle school orchestra.

“So many moments in my life were shaped by that one singular field trip,” she says.

The curtain comes down

Stories like Sutton’s and Saenz’s are numerous in the aftermath of the symphony’s June 16 announcement that it would be no more, as are the newfound worries for cultural accessibility in a city that is now the country’s biggest without a full-time symphony orchestra.

Those concerns extend to leaders of other local performing arts institutions, including Musical Bridges Around the World (MBAW) CEO Anya Grokhovski. A Moscow native who came to Texas in 1991, she’s seen firsthand – both in San Antonio and across the world – the importance of consistent visibility for local performing arts.

“Symphonic music is just as important as museums,” Grokhovski said. “The San Antonio Symphony is a cultural aquifer of the city. We're taking care of our water aquifer, and when we're looking at cultural life, that's what the symphony is.”

Grokhovski added that the orchestra attracted world-class musicians to help keep classical music alive in south Texas over the decades, planting their roots here in the process by buying cars, finding houses, starting families.

Had things gone differently, Derek Mitchell, a trombonist with the symphony since arriving in 2018, might have become one of those adopted San Antonians. Instead, he counts himself lucky that he has the flexibility to move elsewhere and continue playing music; he’ll soon be en route to Arizona.

“If San Antonio was going strong and it was in a good place, I probably wouldn't have taken that Phoenix audition, because it's kind of a lateral move,” Mitchell said. “It's easy for me to pack my things and go. But a lot of other people, they have their entire family here. They have a house here, all their friends are here. Their life is here.”

There’s the impact to the culture of San Antonio, and there’s the impact to the community of San Antonio. Plans have been either altered or otherwise put on hold for the musicians who played with the orchestra for years, and it’s done the same for the future professional performers Sutton has taught at Steele for nearly a decade.

“This is kind of a blow,” Sutton said. “Like a little bit of a reality check that maybe they needed, but probably didn't deserve when they were in their high school years planning their careers.”

Youth Orchestras of San Antonio, though tangentially linked to the symphony, is a different entity that will continue on.

At the same time, some who played in San Antonio as a stepping stone to bigger stages wonder about the long-term viability of musical incubation here without a full-time symphony to help foster young passion. That includes Markus Osterlund, who joined the San Antonio Symphony right out of college and considers it “a formative experience.”

“I worry for the kids in the city who no longer have a symphony to attend and may lose orchestral instructors to learn from," said Osterlund, a horn player. "It's nearly impossible to make it without that resource available when you're a student."

Today, Osterlund performs with the National Symphony Orchestra at the Kennedy Center.

'That's hard to understand'

The symphony’s dissolution was the end result of a prolonged standoff in labor negotiations, which began last September when the symphony board submitted what they called their “last, best offer” to keep the group running. Both sides had agreed to reopen a contract, ostensibly for discussions about pandemic relief.

That final offer set forth from board executives last fall instead called for slashing the salary of a full-time orchestra member in half, while reducing the number of those positions from 72 to 42.

"That's when a lot of the tension really started, because we felt like we actually gave a lot to stay together and help out the organization during the pandemic,” said Brian Petkovich, who had been with the symphony since 1996.

Petkovich and his peers responded by drawing a line in the sand, saying it was their only option. Most every symphony concert since then had been canceled as a compromise remained elusive and rallies were held outside the Tobin Center, the symphony’s downtown home for several years.

Meanwhile, the news wasn’t contained to the Alamo City. As part of a national call to action last year, peer symphonies in other major cities – including Nashville, Baltimore, Atlanta and Fort Worth – made donations to the San Antonio Symphony even as they were coping with their own financial challenges.

That included $10,000 from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, of which James Smelser has been a full-time member since 2000. Also the current chairman of his group’s members committee, Smelser has been involved in the kinds of conversations about what has to be done to keep a big-city symphony alive.

To him, the San Antonio board announcing bankruptcy came off as “you’re tossing in the towel.”

“And that’s hard to understand,” he said, adding that many past members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra played in San Antonio first. “Managements always talk about sustainability, 'We need to be able to sustain this in the future, we can't continue on this model.’ But somehow the arts must prevail.”

Artists elsewhere in Texas have lamented the symphony’s end as well, including Abby Powell. A chorister with the Houston Grand Opera, she says the development is dispiriting in an industry where sacrifice is inevitable and success not a certainty.

The concern is amplified because of San Antonio’s size, she says.

“I'm honestly terrified about how most big cities can ensure the longevity of groups that practice the arts if an institution as large as (the) San Antonio Symphony can dissolve,” Powell said. “When an 83-year-old symphony folds, it tells people like me – who have dedicated so much of our lives to our craft – that what we do doesn’t matter to most people. Our pocketbooks don't matter. These friendships and this community doesn't matter.

“That's the message it sends, which is absurd.”

Over the last several years, extending past the start of the pandemic, the amount of money allocated to the San Antonio Symphony by City Council via its annual budget has decreased. In 2018, the city allocated $460,500 to the organization, amounting to 4.2% of the arts and culture budget, down from $614,000 (or 5.7%) the year before.

By last fall, the symphony’s allotment was down to $336,585, or 3.1% of the arts and culture budget for 2022.

Councilmembers Mario Bravo and Phyllis Viagran – who both serve on the health, environment and culture committee, and were both sworn in in June of 2021 – view the dissolving of the symphony as an opportunity to revive something better in its place.

“We need to look at arts differently,” said Viagran, adding she was disappointed but not surprised by last month’s development. “We need to look at it as not just a business, but as something that tells the story of the community, as part of the healing process in south Texas. I think we’re looking at a push of sustainability.”

Bravo called the symphony’s absence “a chance for a restart,” and says his office has reached out to the musicians to see how he can help them meet their new goals.

“Today’s City Council is very supportive of the arts,” he said. “But I think that also we don’t want any organization to be overly dependent on us on a regular basis.”

Powell, however, wants governments to be more involved via subsidies for artists. And Saenz, who says she’s disappointed her children can’t have the same formative symphony-going experience that she had, expected more to be done when the symphony found itself at a crossroads.

“It feels like another failure in preserving the arts in what I’d consider an artistic culture and city,” Saenz said. “It’s honestly heartbreaking.”

A new mission begins

But Saenz and others who miss the symphony aren’t at a total loss.

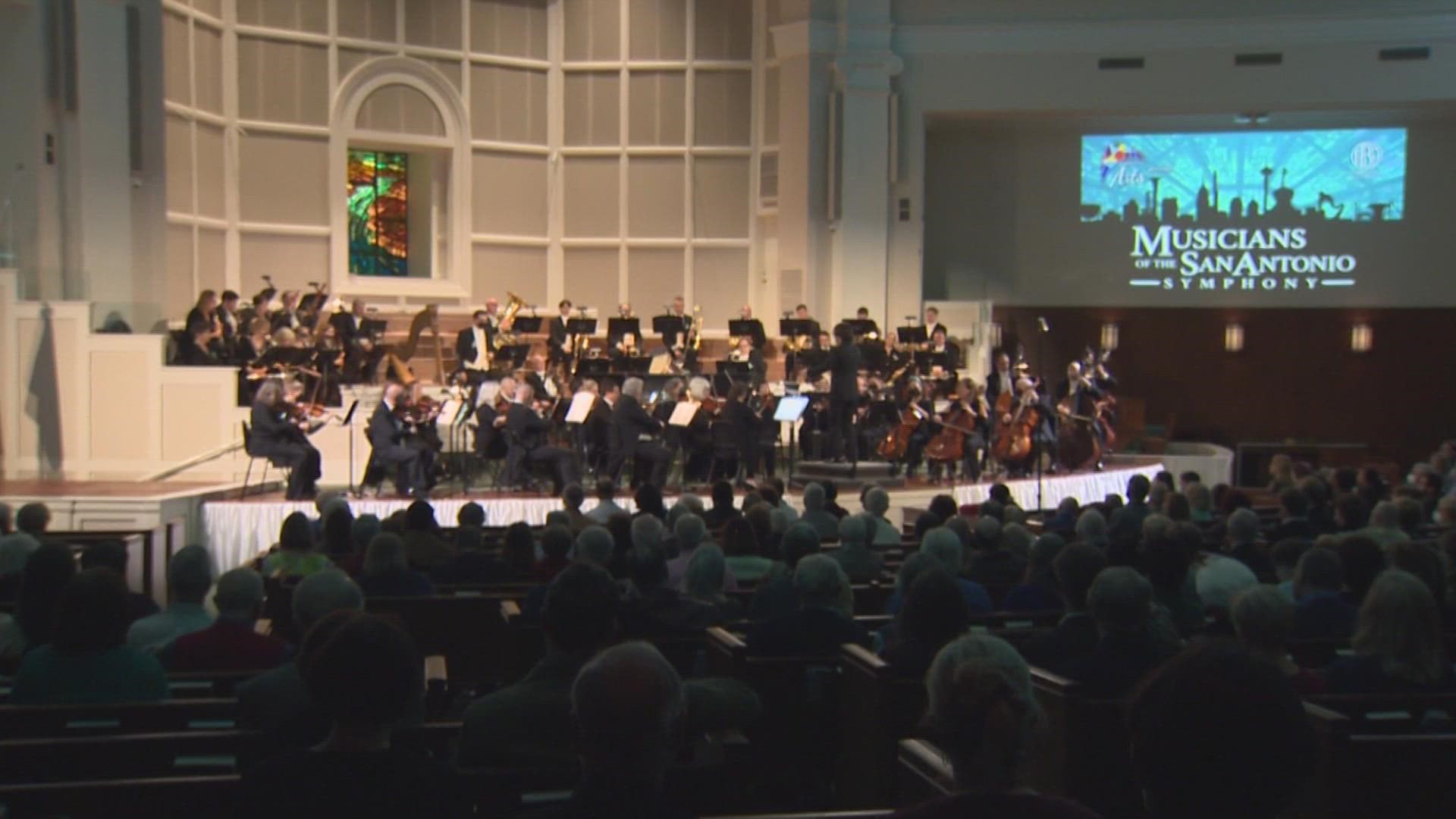

The four weeks since the symphony’s bankruptcy announcement have been a period of reckoning, but also of readjustment. Musicians of the San Antonio Symphony (MOSAS), a new nonprofit formed during the strike, has already been focusing on the latter, having played a handful of independent spring concerts at First Baptist Church while organizing fundraising efforts.

Petkovich has pioneered those fundraising initiatives for MOSAS, which has invited past music directors of the defunct San Antonio Symphony to help create melodies and memories once again. And, Petkovich says, plans are underway to continue bringing music to the city’s youngest audiences later this year.

"We're doubling down on the idea that we need to be out in the community, out in the public, in front of schoolkids,” he says. “That doesn't get a lot of press, it doesn't get a lot of marquee attention, because we're not selling tickets. But I think that's a really important part of our mission."

Petkovich’s goals echo the sentiment shared by MOSAS Chair Mary Ellen Goree in the days following the bankruptcy announcement. At that time, she said the objective was to keep the music playing while laying the groundwork for a potential “successor organization.”

Grokhovski is just one local musician looking forward to when that day comes.

“Hopefully there's enough energy and enough people interested in building something new and maybe even more spectacular—that would be the hope,” she says.

“We don't want this rich tapestry of music that history has spent thousands of years weaving to come unraveled,” Powell added.

While there are limits to what MOSAS can do with its current framework, Petkovich says they’re also afforded a certain artistic flexibility. The next objective: creating a financial sustainability to match.

“This,” he says, “is about asking the big question of how we're going to support and fund the organization over the next 83 years.”