The new blue: SAPD cadets share the weight of change before hitting the street | Together We Rise

By mid-December, the cadets of SAPD 2021-B should be on the street as San Antonio police officers. But do they bring anything different to the job?

Inside the Carver Community Cultural Center's Jo Long Theatre, four San Antonio Police Department cadets and the lieutenant who was on the team that chose them sat center stage to bear the badge.

The theatre is the likely site for their transition from cadet to officer. Ahead of that day, the future police officers opened up in that space about becoming a police officer in a climate of intense scrutiny.

Common themes like service attract them to become peace officers. There are also parts of the job they see as a challenge. For starters: the way they said the media portrays them even as they acknowledge an imperfect history.

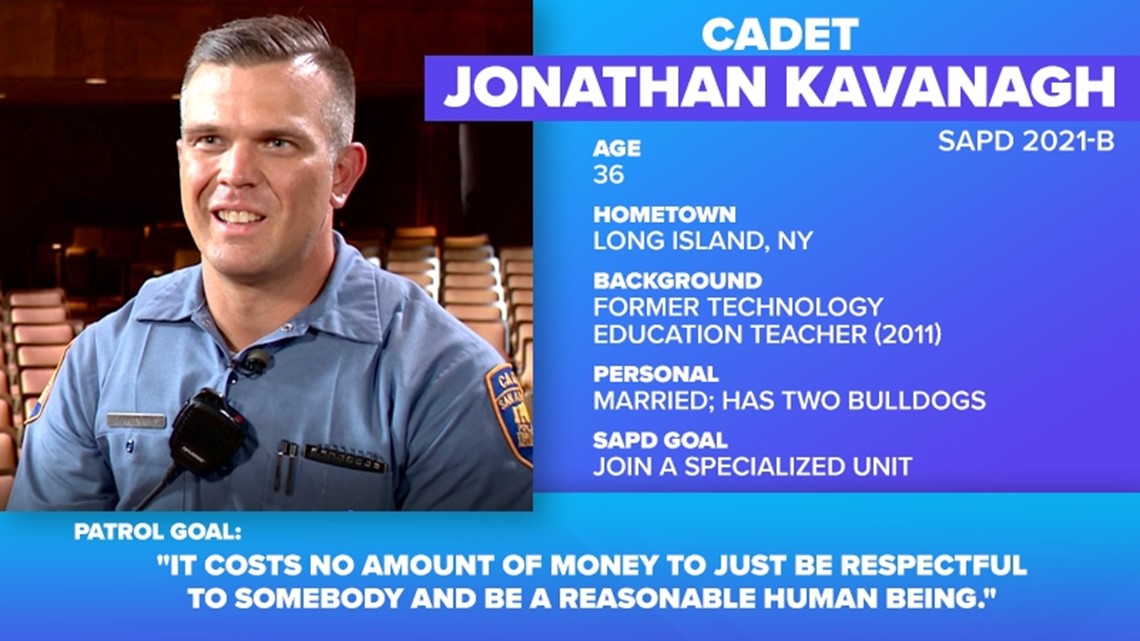

Jonathan Kavanagh Former technology education teacher

Jonathan Kavanagh wanted to be in law enforcement, but he was a teacher. The 36-year-old said he failed to become a state trooper in New York. His first attempt at becoming a San Antonio police officer was not successful.

According to Kavanagh, his nerves got the best of him during the polygraph test.

"I used to be a teacher since 2011," he said.

The Long Island, New York native, believes he can use skills from the classroom out on patrol. The former technology education teacher said he understands the human struggle.

"I've had interaction with people who are extremely affluent, and then both, you know, the complete opposite end of the spectrum," he said. "Not knowing where their next meal is coming from. And to be able to talk and relate to both those people in an equal way, I think is a good tool to have in my tool belt."

Kavanagh said the SAPD Police Academy changed him. He also came into the academy with a mindset of change.

"I want to help change that perception of law enforcement," he said. "Being, you know, in a negative light."

According to the future officer, he feels tremendous support from the community for police. But he also hears the call for reform.

"I think the reform starts with, with everybody," Kavanagh said. "I think the police and the community should be at the same level."

The cadet said both sides need to work together because being respectful and reasonable are cash-free currency.

His greatest confidence coming onto the job is knowing he will help someone.

"If I were to take this uniform off and walk around, I'd look just like everybody else," he said.

Even so, Kavanagh said he would be nice until it's time not to be nice. His greatest fear is not going home to his wife, family, and two bulldogs.

"Just do the right thing to begin with," he said. "And you shouldn't have a problem."

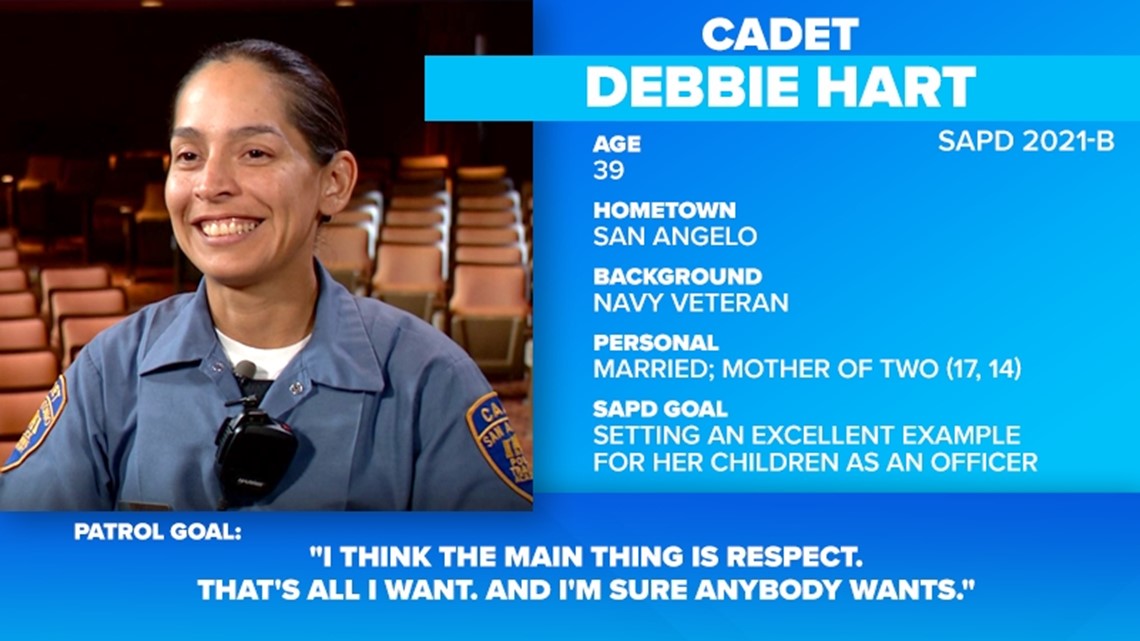

Debbie Hart Navy veteran

Cadet Debbie Hart is a San Angelo native who got a chance to move closer to home from Virginia.

The 39-year-old wife and mother of two teens worked at a detention center. She is also a Navy veteran who laughs at her younger perception of police.

"When I was a kid, I used to watch COPS all the time," Hart said. "So that's how I thought it would be. And as I got older and then come into the academy, it's nothing like that show."

Hart said the SAPD experience had given her so much. Even at five feet tall, the process of becoming an officer stretched her.

She is one of 37 cadets remaining in SAPD 2021-B. 11 members of her class did not make it.

"You have to have in the back of your head: Why did I join? What are you here for," she said.

Her time in detention work in Virginia gave the future officer an up-close look at officer behavior. More specifically, how officer behavior impacts suspect behavior.

"I think the main thing is respect. That's all I want. And I'm sure anybody wants," she said. "It sounds simple, but it's not."

Respect, Hart believes, will make her job easier when she starts to patrol.

According to Hart, her family is supportive. Her children have questions about her job. They especially want a greater understanding of the conflict between officers and marginalized communities frequently shared on social media and top stories on the evening news.

"I know they watch the news, and they see how officers are portrayed, but then they see the good side also," she said. "If they see their mother as someone you know, in that line of duty. I know they'll have more respect for authority."

Her greatest fear as an officer is not going home to her family.

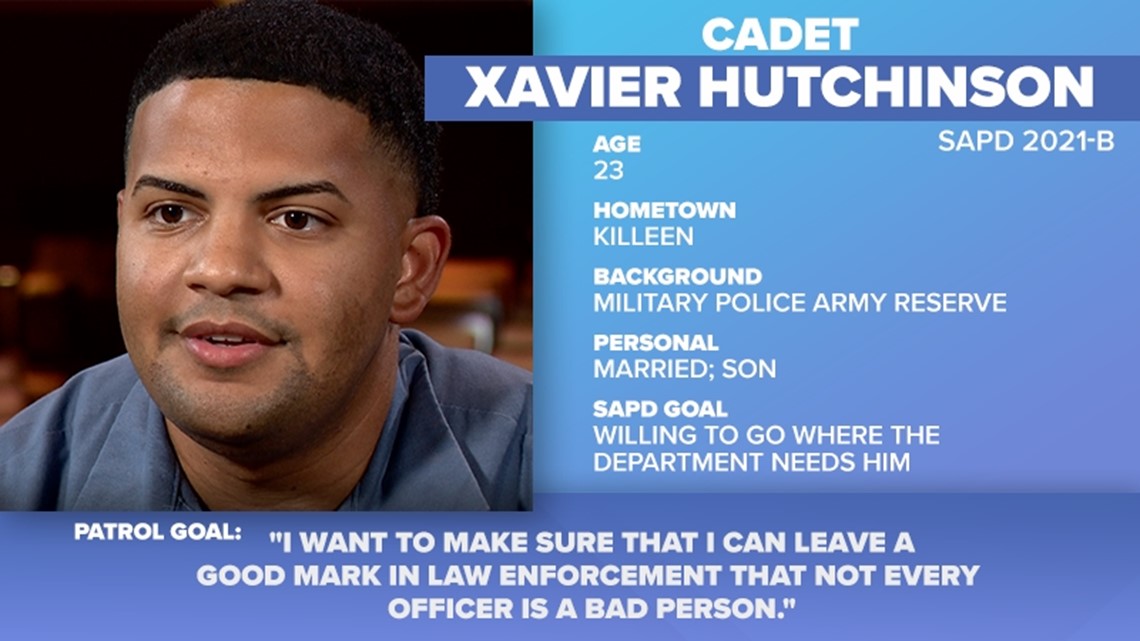

Xavier Hutchinson Army Reserve

At 23-years-old Xavier Hutchinson's decision to become a police officer was not met by his family with confetti and champagne. The cadet did not get deterred.

He said signing up for the Army came with a level of concern too. Like his fellow cadets, the husband and father lives with the fear of not going home to his family. But he said it's not top of mind.

"I'm willing to go into whatever," Hutchinson said. "And whatever consequences it is---I just tell myself 'It is what it is,' to be honest."

Hutchinson wants to get viewed as relatable on his beat. The kind of officer the community can talk to about anything.

"Most of this job is communication with people," he said. "You encounter a lot of people. So the way you come off, that's how they're going to view it."

His view of police was not always a good one. Hutchinson said an officer pulled him over as a ninth-grader.

"I had bought a vehicle. I had false tags on it--to a Mercedes Benz, which I didn't know about," he said. "I had no driver's license or insurance."

Hutchinson remembers the officer's approach as one that lacked respect and was rude.

"When his partners got there, he just randomly pulled me out the car, threw me to the ground, handcuffed me, and didn't explain to me why I was being placed under arrest," he said.

He got out of jail. His mother's words about the incident cleansed the bad police encounter taste from his mouth.

Now, Hutchinson is on the verge of becoming what he once viewed negatively. He takes that life experience back onto the streets.

"Just growing up in a rough neighborhood," he said. "I know how things are. So there's no way I would degrade somebody like that and put them in a situation like that."

Tristan Scepanski UTSA Criminal Justice graduate

Tristan Scepanski tried nursing out in college and didn't like it. The 23-year-old knew she wanted to walk in the big footsteps of her father as a San Antonio police officer.

"Even in today's climate, I know this is exactly where I want to be," she said.

Scepanski is a Criminal Justice graduate of UTSA. She got life lessons at home from growing up as the daughter of a policeman.

"You're not just another person; it's a family," she said. "And we're going to not only take care of each other but take care of our community."

The former retail worker hopes to make an impact in her patrol area before they need her assistance.

"I don't want the only time people to encounter the police is when they're having a, you know, their bad crisis," she said.

Scepanski is looking forward to building relationships as she recognizes cries for change.

"We can't keep stepping back and making steps back towards a negative relationship," Scepanski said.

The cadet understands how easily bias toward her profession can happen. If it weren't for her father and his fellow officers, she could have felt differently about police.

"I've been pulled over before in a different county, and the officer that I dealt with was not Mr. Friendly," she said. "So it did kind of affect me there."

Her greatest fear is the same as the other cadets.

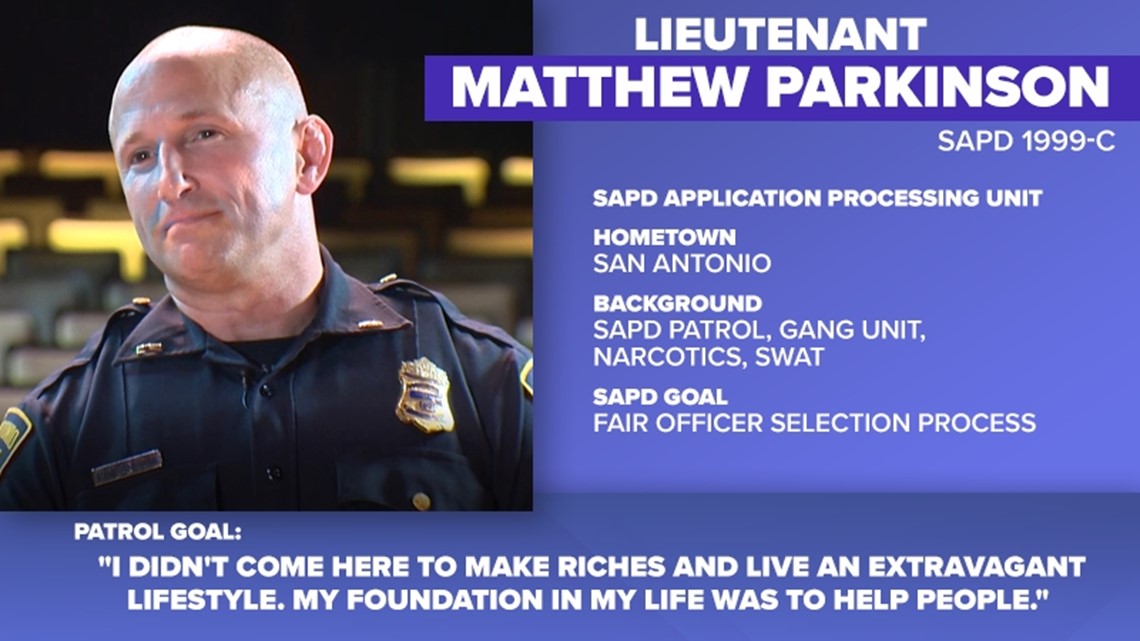

Lt. Matthew Parkinson 'It means a lot to me'

Lt. Matthew Parkinson comes into any situation with an electric personality. He was a member of cadet class SAPD 1999-C.

Raised by a single mother who worked as a dispatcher, at one point, Parkinson remembers weekend breakfast time exposing him to law enforcement.

"I feel like I live in a movie," he said.

He's worked patrol, the gang unit, narcotics, and S.W.A.T.

"When you become a police officer, you do see a different side of life," he said.

Now, he's with the applicant processing unit at SAPD. The team selects future officers who apply on SAPDca.

"Our philosophy of trying to get people on and give people a chance that's changed," he said.

Parkinson said the process allows them to do a deep dive into the backgrounds of prospective officers. He said they could dig until a flaw or skeleton gets found.

"How far do we go?" he asked.

According to Parkinson, he wants to be fair. The department will not overlook certain mistakes from the past. But they still have to hold a high standard.

Their lengthy application, criminal background checks, and interviews to feel candidates out are only a part of the journey to wearing the badge.

"The uniform that we wear it means a lot to me," he said. "I worked hard in the academy and going to college for this uniform."

Parkinson said he wants to make sure every applicant gets a fair shot at becoming a department member.

Cadets get $45,000 a year as they traverse a nearly nine-month process to becoming an officer. Patrol officers make between $53,748-$73,224.

"I hope and pray that we do select the best that we can," Parkinson said.

He knows that even at that standard, officers are not infallible.

"When I see a guy not doing his job that reflects me," he said. "If he's doing something with bad intentions or ill intentions or with a bad heart, that reflects me too."

Parkinson said officers must be accountable for their actions. Earning the right to wear the badge starts after the academy, he said.

He said SAPD is not drafting killers to dress in blue.

"We're not that guy that put their knee on somebody and wants him to die," he said. "I've never woke up and said, man, go kill somebody today."

For him, the department's foundation is service to the community. Parkinson said they don't want the bad apples.