SAN ANTONIO — One by one, they walked into the Briscoe Western Art Museum's Clingman Education Gallery, a neutral space afforded by the Briscoe, upon request, to conduct the discussions.

Three days of interviews with recordings nearly exceeding eight hours produced conversations about a conflicted and deadly past. The lengthy talks also yielded a common ground for resolve.

Ten people who have distinctive views on the relationship between police and communities of color agreed to share their experiences, truths, challenges, and solutions for the KENS 5 Eyewitness News diversity collective 'Together We Rise.'

Like Together We Rise, its series of parentage, Police & Race pledges to showcase the issue with the hopeful notion of change.

Police & Race is broken down into three parts: The voices of change, the police, and the solution.

To ensure the volume of information is easier to digest, we've changed our typical format to accommodate the views and facts from our experts.

"How do we get from the anger to let's work this out and find a solution to change?"

Debbie Bush, Reliable Revolutionaries

Who: Debbie Bush is the aunt of Marquise Jones. San Antonio Police Officer Robert Encina killed him on February 28, 2014, following a fender bender in the drive-thru at Chacho's and Chalucci's.

Jones, 23, ran from the vehicle. Encina shot the father of one in the back, claiming Jones raised a gun.

A Bexar County Grand Jury sided with Encina, as did a jury in a civil trial--clearing him to return to patrol.

The Problem: "The lack of trust. The lack of transparency and accountability. There's a major problem across the country. When our loved ones are killed, it's like the police officer is---they cloak him and protect him and make sure he's ok and everything. They don't respect the families that have lost loved ones. You know, we're swept away.

"They look at Black people as criminals---like even our children. The police act like they're above us, and they're our slave masters. And we do what we're told. And if we don't, then we're going to suffer the consequences.

"I don't like saying it, but they portray us as savages. And it's to the point where it doesn't matter what your job title is, where you work, where you go to school. I have friends and stuff---they won't even call the police if something goes wrong because they're afraid that they...it will be escalated and someone will die. We're afraid to live. We're afraid to do anything because we feel like if we do, they're going to find something to pick at us about---to arrest us, or we end up dead.

My son has made the decision not to have children because he'd afraid of the climate we live in. My son actually put a plastic-like cover on his door that he has his registration, driver's license, and insurance information that he keeps right there. So if he gets pulled over, he doesn't have to make any sudden movements. He literally will just go like this and hand it to the officer."

The Solution: "How do we get from the anger to let's work this out and find a solution to change---and change the narrative? You take an oath, no matter what the skin color is, to protect and serve. They need to sit down with the community. And I'm not saying the church---you need to sit with the community, not pastors and in all of those kinds of people. Your community. The people who you patrol.

"We have a dark side that no one wants to talk about. They want to just talk about what the police do as good things, but what about the bad stuff? What about the bad officers? Removing bad officers from the force, the DA indicting these officers, especially if you know it's in your face. Recognize the families. Recognize us. Recognize our pain; recognize who we are. Recognize our loved ones that we lost. Give us some type of respect.

"It hurts because I am---I've never been anti-police, but I'm anti-police brutality."

"We have a job to do in the DA's office, and all we can ask is give us the opportunity to do that job."

Joe Gonzales, Bexar County District Attorney

Who: Joe Gonzales took office in 2019. He won the job after beating incumbent Nico LaHood. Before that, Gonzales served time as a criminal prosecutor. He spent most of his legal career as a criminal defense attorney.

The Problem: "I spent the large majority of my time as a criminal defense attorney, and it also brings me a unique perspective to the office. I did believe there was a disparity in terms of who is making arrests and who was allowed to make a phone call and be released. And so that was part of what I remember as a young defense lawyer, you know, twenty-five years ago.

We have systemic racism even today. We see it in law enforcement. We see it in the prosecutor's office. We see it in the courts. We see it in education. We see it in business. And so, the best thing we can do is recognize that it exists. That's not to say that all cops are racist. All lawyers are racist. All judges are racist. But I think sometimes we have implicit bias that we don't recognize. I don't know that I've ever been involved in this office where I can say the only reason someone was arrested or charged with a crime is because of his or her race.

(On shootings where police kill or injure someone in the line of duty) We have to basically prove that the officers committed a crime and that they're, and I hate using this word---it's in the statute. But, we have to disprove that the officer's conduct was justified. And that's a very difficult thing to do because oftentimes, officers have to make a split-second decision about whether or not to fire their weapon. To meet with families and to tell them that, you know, first of all, nothing that we do is ever going to bring their loved one back. But we have to make decisions as lawyers, not based on emotions, but based on the facts of the case. And we have to make decisions about whether or not what the officers did amounted to a crime.

It's like ripping your heart out of your body to hear that. And I understand that. And I feel for them. I've thought to myself, well, what if it was sitting me sitting as the father or the husband and that happened to my loved one? How would I feel? And it stays with you. It still has stayed with me, the visits that I've had with the family members. But again, that's those are the real, real tough decisions that we have to make. But we have to look at it through the lens of the law.

We have a job to do in the DA's office, and all we can ask is give us the opportunity to do that job."

The Solution: "I joined a group to say that we're not going to be asking for endorsements from any police unions. I want to keep that relationship far away to where people don't question my motives because they're writing me a check.

We created a civil rights division that is focused on only handling officer-involved shootings and claims of excessive force. We have a paralegal in that division that reaches out to the family to let them know that we're going to be monitoring this case, monitoring the progress of the investigation.

Another way that I've changed the way that we handle these cases is that I've committed to the community that I'm going to take everything to the grand jury. Right now, the law prohibits us from releasing any grand jury activity. That's not to say that we can't release the facts of the case and the work that we did on a case to help the public understand, help the family understand why a grand jury might have no-billed the case. We were going to prepare a memo that will be available to the public."

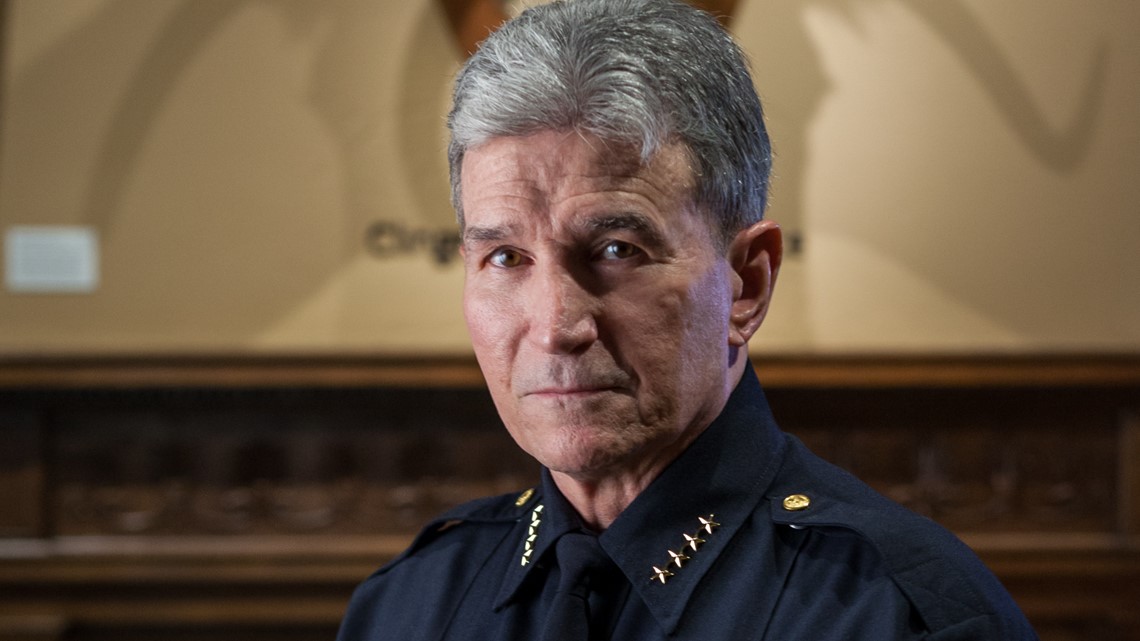

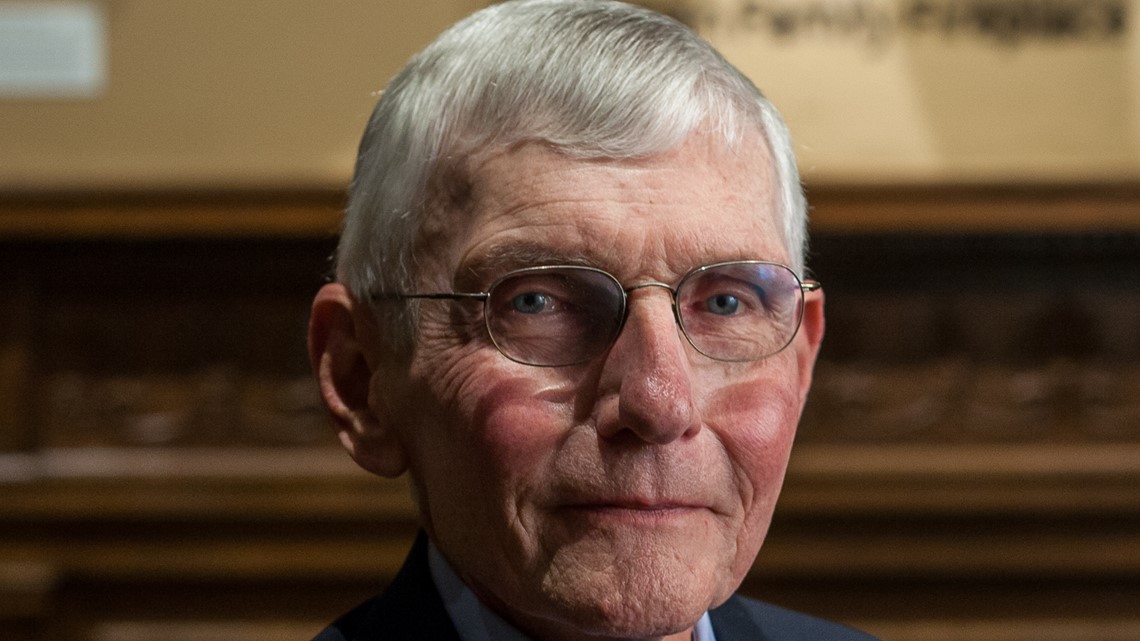

"I like to be on the enlightened path; the enlightened path is always looking for better ways to do things."

William 'Bill' McManus, San Antonio Police Chief

Who: Bill McManus became a police officer on June 1, 1975. It wasn't his first or last choice. He wanted to become a professional football player. When that didn't work out, he set out to become a physical education in France. As he pursued his dream of wearing a beret as an educator after going to Martinique, McManus became a police officer.

He credits his rearing as an officer to African-American leaders in his ranks and life-long relationships with community members wherever he got to work.

The Problem: "These horrific videos that we see or that we've seen, there's not one police chief that will defend any one of them. Granted, you know, we're seeing a segment of it or a clip of it and don't know the background. I'm not one---I've learned early on not to jump to conclusions about things. There are some things that you just can't justify. I mean, all you gotta do is look around the country and see what happened when somebody says, hey, I'm pulling out my wallet, and boom, you know. I mean, there's videos out there that justify that fear. There's stories that circulate that that that justify that fear. I get it.

What's frustrating to me is---you know, we take x number of steps forward in terms of changing policies, making substantive change in the department, and then when something happens---and it doesn't matter how small the department is or how remote the area is, where the department is located, if something bad happens, it affects every police department in the country, and it sets everybody back to square one."

The Solution: I take my role as a public servant literally. We've been probably one of the most progressive police departments in the country in terms of our policies and our practices. We have done so much changing our policies, revising our policies, implementing policies. To make sure that our policies are the best out there as they pertain to our practices on the street and the way we deal with people on the street. How do we get the word out that all these things are being done? Because apparently they're there, and they're not right now getting out the way, I'd like them to get out to let people know.

I like to be on the enlightened path; the enlightened path is always looking for better ways to do things, always looking at the horizon to make sure that, you know, we see what's coming our way and we can prepare for it. I had seen and read reports---where in the past, before de-escalation became something that we taught and practiced, someone might have wound up getting shot. And I've seen where we've avoided that on a number of occasions. De-escalation is working there. It's kind of hard to say, hey, guess what guys? We didn't shoot this guy today because this is what we did. That's not something that you put out on social media, but it's something that's very real, and something that is really making a difference in officer-involved shootings.

And as far as I'm concerned, I love to use this phrase. There's no finish line. You know, we are about continuous improvement in everything that we do. Everything."

"The moment we go back to sleep is the moment we lose hope for change."

Pharaoh Clark, Reliable Revolutionaries

Who: Pharaoh Clark thinks of himself more as a community advocate whose focus is leaving a better tomorrow for the next generation. His activism, according to Clark, is more about healing and fixing problems. For him, it started with an effort to remove a statue paying homage to soldiers of the Civil War that used to be in Travis Park. Civil rights and social injustice came next.

The Problem: "We've heard from their side, well, there's only a few bad apples, and no one hates a bad cop worse than a good cop. Well, if that's the truth, then what we're asking is that you work with us to find solutions on how we get rid of these bad cops. Because there's only a handful, there's no need to address it. That's ignorance. And to continue to do the same thing and expect different results, that's insanity. I shouldn't be seeing an officer for the first time when I'm being arrested. They should be in our community in a way---in a more positive and productive way on a regular basis.

For years what we've said is, well, there's a crime in this community. So the way we deal with that is by throwing officers at that community, and we have to get rougher with them. We have to get stricter on the laws. And I think time has shown that that doesn't really work.

Our police officers are being trained to look at civilians as a threat. And this, I think, is a very flawed practice. And I believe this is where a lot of our problems are coming from. Is their job dangerous? Most definitely. Without a doubt. Their job is dangerous. However, when they're being trained that every civilian is a possible threat, then you're dealing with situations where you can be coming in with this heightened awareness, this heightened sense of danger, and it can lead to these types of mistakes happening.

We shouldn't have it to where a certain population does not feel that they're safe to walk the streets or they don't feel like they can call an officer because they're scared. If I call an officer to come help me with my mentally ill son, will that officer show up and help me? Or (will) that officer show up and shoot my son?"

The Solution: "I think change for me, it looks like accountability, and it looks like a partnership. I don't think true change is going to be possible until we see a true partnership between the community, the city, and the police department, and all have to work together in order to get to that change.

What's going to make sure that we decrease the crime in our community is making sure that we have economic investment and youth development. We have to make sure that these communities that we're talking about have opportunities in them so that the youth are not going into a life of crime.

Do I believe that we're anywhere close to where we need to be? No, but I think we have seen a difference in reactions, even in recent cases that have dealt with police brutality, where you see the system taking a lot more seriously, acting a lot quicker on these issues than they ever would before. And I think that in itself is showing the change. As long as we're willing to sit down and have those open conversations, those uncomfortable conversations, as long as we're willing to have honest dialect that pushes that needle forward, no matter how slow or long it takes, change is possible. The moment we go back to sleep is the moment we lose hope for change."

"What you don't see is the tens of thousands of police-citizen encounters that go perfectly fine."

Michael Smith, J.D, Ph.D., Chair, UTSA Dept of Criminal Justice

Who: Michael Smith is a nationally recognized criminologist who is a former police officer. Smith said he worked in Richmond, Virginia, on the city's southside in the early part of his law enforcement career. The area was impoverished, almost exclusively African-American, and high crime. He said he faced the tensions one might expect a young white officer would. Smith also recalled garnering community support. As a scholar, he gets to marry academics and criminology.

The Problem: "By and large, you know, the history of the Black community and the police is fraught. It's often tension-filled. For a long period of the history of Blacks in the United States, the police were not, you know, they were there to oppress them. Right? They weren't there to lift them up, to protect their constitutional rights. They were, you know, that was not their role for 100 years or more. I don't think you can escape that historical legacy.

Having said that, our police have come a long way. The level of professionalism, the level of training, the level of respect for the rule of law, the law itself has changed significantly. But that doesn't undo, you know, over 100 years of oppression that, you know, African-Americans have felt at the hands of the police prior to the civil rights era of the mid-60s.

When you're watching the internet, however, you choose to get your information...You would get the impression that there's this, you know, pandemic of police violence going on right now in ways that are different than we used to be in the past. And that's not true.

The general public has, I think, an impression now that the George Floyd cases of tragedies are more normative, and they're not at all, you know; they're aberrations in the extreme.

What you don't see is the tens of thousands of police-citizen encounters that go perfectly fine. Right?

People of color and who live in communities of color are in no more danger from the police than they were last year---or two years from now, prior or five years or ten years. But they don't---but they feel like they are right? Fear of crime is up here. The chances of being victimized is way down. Right? Why are people much more fearful than the data suggests they should be? How do we bridge that? How do we bridge that gap?

By and large, San Antonio and its community and its police department have a pretty good relationship compared to a lot of places."

The Solution: I think communities have got to to to feel like there aren't obstacles in the way, particularly communities of color, have to feel that there aren't obstacles in the way of holding bad cops accountable. And I think in many communities of color, they don't feel that way.

To me, change looks like accountability. It looks like better training for sure. What we need is more training on what to do right, how to behave, and how to react appropriately and under stress.

There's not nearly enough training about how to deal with people. Right? In particular how to deal with people who don't look like you and in their communities.

We need empathy. We need to be able to see people as human beings, no matter what the color of their skin is or how much money they make."

"I don't feel like they're fully connected with the community and what's going on for us as they should be."

Ananda Tomas, Deputy Director, Fix SAPD

Who: Ananda Tomas is the deputy director for Fix SAPD. The grassroots organization gained breath during the national reckoning after the murder of Texas native George Floyd.

The organization works on police reform, especially police union contracts and officer accountability.

Fix SAPD took the San Antonio Police Officers Association collective bargaining power to the ballot in May. The police union won the election. Many believe Fix SAPD won the narrative and a chance at change.

The Problem: "San Antonio is a big city with a small-town feel. And I do feel like we do have, especially if you're talking about certain groups such as the San Antonio Police Officers Association. They've built political dynasties and political machines here. And this has become the status quo.

It's not necessarily that they're bad so much as they are very resistant to change and any type of losing any sort of power for them. I don't feel like they're fully connected with the community and what's going on for us as they should be.

If you're talking about bad officers or officers that commit misconduct, they're not just harming us. They're harming other officers. They're tarnishing the name of the police union of the police department.

These are officers that use racial slurs or derogatory statements against other officers as well, or, you know, playing a prank on the women's park substation restroom.

I get very upset and frustrated that they push this narrative that, oh, well, we're not these other cities. This doesn't happen here. When it absolutely does. We have stories of misconduct and abuse spanning back decades.

The Washington Post did a story. We have the highest rate for fired officers (who get reinstated following arbitration) in the nation at 70 percent. That's something that's specific to San Antonio.

So the idea of a few bad apples isn't that big of a problem. It's not true. It is a problem. These are lives on the line. These are livelihoods on the line. And we need to do everything we can to change that because we all deserve better. We deserve more.

You need to have a strong DA that's willing to prosecute. If you have a district attorney's office that has to frequently work with these officers and then has to work to prosecute against them, where is the independence there? Can they truly be objective?

There's the state legislature. We had many police reform bills that were up in the Texas legislature this year, and there's only a few of them left. The main one, the George Floyd act, has basically died.

Then you have to move up to the Federal level. You talk about a Federal registry for officers and their misconduct."

The Solution: "At the end of the day, when we're looking at accountability and safety, I think we all have the same goals. We're just not seeing eye to eye on them.

This is as much about backing our men and women in blue as it is about back in our community, especially when we're such a heavily Latinx community and we, you know, our black or brown community are indigenous. It's about all of us together creating a system in a community that is safer for us.

We can start a change here for our community that can spread across Texas and across the nation and serve as an example and a blueprint of a community coming together to fix a serious issue.

Each little bit counts towards the ultimate goal of getting to police accountability, to police reform, to everybody understanding that black lives matter, that there is an issue in our policing here."

"We're getting chastised from every side, and look for us it's not personal. It's just a job."

John 'Danny' Diaz , President, San Antonio Police Officers Association

Who: Danny Diaz is a veteran San Antonio police officer who is in his first term as the San Antonio Police Officers Association president. In his 29 years of service with SAPD, Diaz worked at the department's South Patrol, Street Crimes, and SWAT. He survived being shot three times during the execution of a drug warrant on Veterans Day in 2010. His tenure as SAPOA president started with a grassroots ballot initiative from Fix SAPD challenging officers' collective bargaining power.

The Problem: "The goal that I have for the association moving forward is as a department---as a whole---as a union---we've not been out in the community the way that we should be. We need to keep that connection with the community. And we lost that. My job now, and my goal was to get back into that.

People see us in a certain light; a lot of it is from what's transpiring across the country. Doesn't necessarily mean it's here. We do have issues. We take care of our own issues. I've arrested six officers in my career. Other officers have turned into officers that are doing things incorrectly. So we police ourselves to the best of our ability.

A lot of people seem to come up with ideas and just run with it without bothering taking the extra step of just asking the individuals that actually do the job if these things work. Nobody asks that.

Look, I'm here to tell you, this ain't the movies, right? Things are done differently.

Now, we're getting into a lot of issues where you see across the country the words of de-escalation, retreating. And that for some officers, that's hard to deal with because a lot of them were raised in this gladiator mentality. Right? You're there for a reason. How are you're not supposed to go and take care of the situation? That's not what this job entails. People call you for a reason because they need help. They don't want you to retreat or leave. They want you to take care of the situation at the best of your ability.

It takes a special person to do this job right. Nobody likes getting spit on. Nobody likes getting yelled at. They're expected to take all of those and then just go on about your business. Mentally, it wears on you for a while if you don't have the right individual.

When I hear the word fear, it upsets me to the point to where...I will tell you that---that's for me as a police officer; it's disheartening because we're here for the people. There's no reason to be afraid of policemen.

It doesn't matter what ethnicity, what race. What have we done to ever...to get that mindset?

On any given day, I could be at a store or at a restaurant in uniform, and a child is acting up. What's the first thing a parent says? If you don't behave, I'll tell that policeman to take you. What do we instill in that child now---to be afraid of policemen?

You get cell phone video; by the time somebody brings it out, they see the finished product. You see the officer shooting the individual. What led up to that point? And those are the things that people don't see.

Think about mindset when you continuously play those and play those and play those and play those; your mind's already trained; that's what actually happens.

Some of the media outlets are just nothing but negative, right? What they don't see is the good things that officers do on a daily basis.

We're getting chastised from every side and look for us. It's not personal. It's just a job."

The Solution: If you look at the city of San Antonio as a whole---and this is documented---our (SAPD's) use of force has gone down tremendously over the last couple of years.

The study that I'm looking at is, how many African-Americans have been shot here since 2017? And it's not done yet. We're looking into it. What I have noticed is that we average---there's about 15 shootings a year that happened after those shootings that happened here. And the majority of them were either Anglo or Hispanic.

If you look at the amount of African-American males that have been shot-- (there's) not even 10 percent there. It's either white or Hispanic. People don't know the ethnicity that is most frequently arrested here in the city of San Antonio over the last several years have been white males.

I bring that up because one person threw that out. All we do is kill African-Americans here. That's far from the truth.

We have done our due diligence. We have told the city manager and city staff that we are coming to bargain in good faith---during our current collective bargaining talks, contract talks. We've done that. We've made some concessions, a lot of movement. We feel enough movement to handle two contracts down the road.

I think a lot of what's wanted is 100 percent their way. (What) We're asking for is what's fair and let's meet in the middle, and up to this point, that hasn't happened.

The accountability is there. The problem is that there's been some issues where people have gotten off on technicalities, just like any average citizen could. Is it making us look bad? Sure. Those individuals---do we want them here? No--- because it makes the rest of us look bad.

February 1st, I became president this year. I've been knocking down, chipping away at walls. And the walls are communication, right. Nobody is talking to anybody. And it seems like the minute I knocked one down, I turn around to start another one. When I turn back, it's up again. That dialogue is vital. We just don't talk to each other.

Let's sit down and work this out because this place here, look; I'm born and raised in San Antonio. I love this city."

"Here we are in 2021, saying we want justice. At some certain point, you have to just become the justice that you want to see. "

Artessia 'Tess' House, Tess House Law

Who: Tess House owns and operates Tess House Law in San Antonio---assisting clients with family law and civil rights cases. House, a former educator, turned attorney said civil rights became her passion as a young girl in the NAACP Youth Branch.

She's notably represented Mathias Ometu, a Black jogger detained and ultimately arrested by San Antonio police last August. Police said Ometu matched the description of a family violence suspect. He was not the actual suspect. But his refusal to lawfully not answer police questions led to an altercation caught on a cell phone video by an attorney watching the incident. The charges for assaulting police got dropped.

The Problem: "I believe that when people see acts of injustice, they are outraged for the moment, but it only lasts for a finite period of time. And, so the real challenge is to ensure that people are engaged---and that they keep their finger on the pulse of what's happening in the community.

So there's systemic racism, over-policing, (the) militarization of policing, microaggressions.

It's important that we back officers that are doing the right thing, but those that will not subscribe to the principles that the community feels is important to police---that they be let go to seek other employment, but not in law enforcement.

We have a provision such as a Freedom of Information Act that allows you to get access to certain footage. However, you will find that there is a firewall preventing persons from getting access to body-worn camera footage because they(Police) say there's an active criminal investigation.

If the video footage seems to bear on the side of law enforcement, it gets released, criminal investigation or not. We should treat the footage the same. You cannot use it as a shield if you find that that footage can be used as a sword.

Think about it, who is funding all of this equipment being used by law enforcement? It's the taxpayers.

I've been in enough litigation to know that what a police officer writes on that report may not be a true and accurate representation of what actually happens on the ground. In fact, you will find that a lot of those police reports do not corroborate what their own body-worn camera catches.

It isn't the body-worn camera footage in of itself--right---that is compelling the public to pay attention. It is what untrained laypersons are catching on their Android and Apple cell phones.

Here we are in 2021, saying we want justice. At some certain point, you have to just become the justice that you want to see."

The Solution: "Rather than fighting against us or ignoring people's perils, tuning in and paying attention to what they're saying---and so if we could get this to translate to our police departments, we'll be much better off.

In order to be an ally, you have to understand that when people are saying we're hurting, pay attention. When people are saying now, the story of the hunt is being told by those that are being hunted because we are using our technological gadgets to videotape what's going on---that debunks your stories written in police reports--you need to listen.

It starts with listening to their side, listening to the story of those people who have stated that they have been victims of police brutality, who are stating that we have some unjust laws that aren't working in my favor. Right? They feel that they have been mistreated (in) some way by those that have been given the authority over them.

All that matters is the law. Think about it in the word law enforcement. The first term is law. It's the law that reigns supreme. And so, at the end of the day, there is no person above the law.

The law has not always worked favorably when it comes to disenfranchised groups; it is not perfect. It's the best that we have, right. It becomes even more incumbent on our legislatures to redraft the law. Right? So there are these living documents that can be modified, changed, and deleted."

"I back the blue, but I wake up Black."

Alonzio Hardin, President, San Antonio Black Officers Coalition

Who: Alonzio Hardin is not only a San Antonio Police Department veteran. He's a military veteran born and raised in the Alamo City. Hardin didn't dream of becoming an officer of the law at East Central High School. Destiny pushed him in the direction of SAPD, where he's one of their Eastside SAFFE unit members. His career choice raised eyebrows and questions---and it still does.

The Problem: "If that was a question that I was asked as a young lad, I would have never said anything closely related to being a police officer. I mean, let's be honest--you know, the African-American community and the relationship of law enforcement, in general, has a deep scar.

I back the blue, but I wake up Black. So I understand.

I understand that the conversations in an African-American household are going to be different from that of a Caucasian or even a Hispanic household. Because that conversation is going to be based on the color of your skin and how you're going to be treated because of the color of your skin.

There's a reason why the majority of the African-American community does not trust the police. There's a reason why.

Having conversations, those deep conversations, and when you're able to hear and listen to some of the experiences, even as a police officer, I say like, wow. Why? You know, really? Is it? Did all that really happen just because of the color of your skin?

It's real. It hits home, and you cannot be one to say, Nah, that's not what happened. Yes, it is. That's exactly what happened.

That's exactly why the conversation---the volume of the conversation about policing in Black communities is so loud right now because there are issues.

It is a constant balance of seeing it from an African-American man and also seeing it from an African-American man in uniform. There is a difference.

I've been called Uncle Tom. A sellout. How can you even wear that uniform? You...You think like them. You act like them. And we haven't even had a conversation. They know nothing about me. I'm here because a situation has gotten to the point where the police need to be involved. And it just happens to be me, a Black man in uniform.

I was in a setting, and it was phrased as reverse racism. What some may consider racism or prejudice, you know, I get it simply because of my uniform.

Don't even look at the fact that I'm Black like you, but automatically because you see me in this uniform, I'm a sellout. I'm not for the Black people. I'm not for the Black community. And that's just not true."

The Solution: "A police officer's encounter with anyone in the public, specifically African-American, it doesn't always have to be a negative encounter. It doesn't.

There's a lot of prejudgments that need to stop and give that person that human dignity, that human right, that decency to be treated fairly based on that initial situation, whatever that encounter is.

Community engagement, community involvement, sitting down talk and having those uncomfortable conversations and just clearing the air and being totally transparent.

Understand you don't have all the answers, but you can be a part of the solution.

At this particular time, at this particular juncture, with the relationships between police and the community, it's a time of healing. It's a time of rebuilding.

This is a time to acknowledge it, not forget about it, and not try to make excuses about it. But this is a time to fix it."

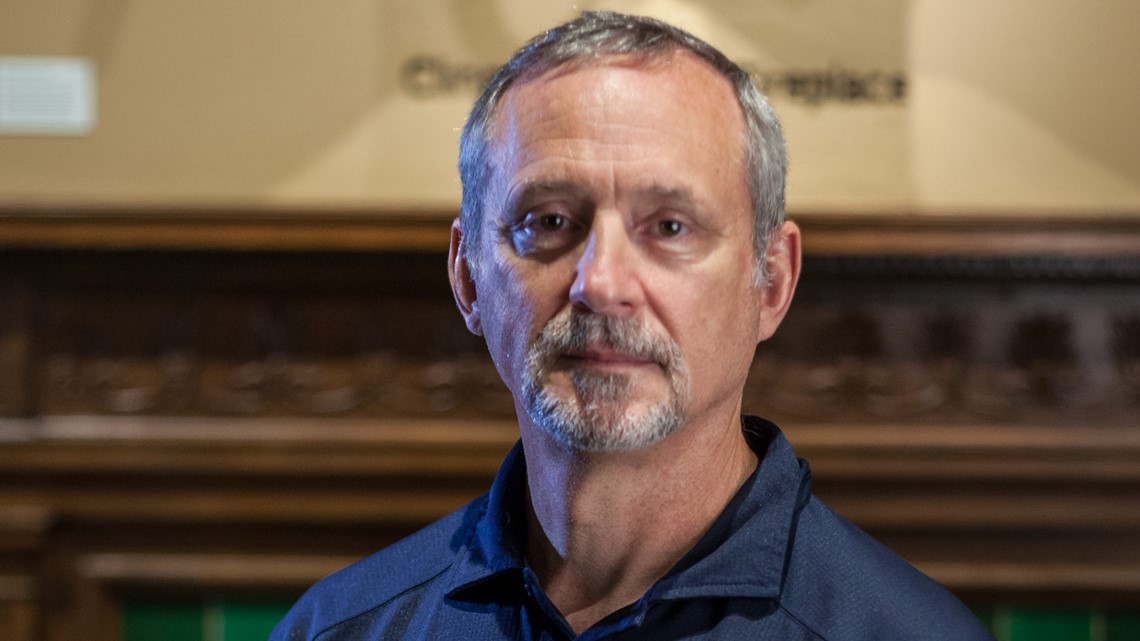

"I think that history weighs us down, and it keeps us from getting to something approaching a solution."

Geary Reamey, Professor, St. Mary's University School of Law

Who: Geary Reamey is a professor of law at St. Mary's law school. He's approaching 40 years at the university. Reamey specializes in various legal areas, including criminal law, constitutional rights, international human rights, and police misconduct. He also served as a legal consultant for the Irving Police Department.

The Problem: "I think policing and race probably best boils down to understanding implicit bias because I think that's more what it's about now than it is about overt racism.

I think more often when we see these terrible acts that occur with racial overtones that those are likely to be the product of implicit bias.

If you were to talk with police officers after the fact, I think in most of those instances, you might conclude that they were not consciously racist. They didn't go into that interaction thinking: This is a Black person. This is a Latino.

But they did go into those interactions with what very often is an unconscious set of understandings and stereotypes. That then colors their actions.

So, I think we have to understand that when we talk about implicit bias, we are doing so with the understanding that we all have them. And for the most part, they are pretty benign.

But they are not benign when we have somebody with the kind of power and authority that we vest in the police interacting with a citizen. Then, those biases can become dangerous and even deadly.

I think that history weighs us down, and it keeps us from getting to something approaching a solution. That informs everything that we think, say, and do.

For everyone who is in a minority community---who has this history of dealing with the police, they are going to see whatever is done today through the lens of what has happened before. That's not unfair. It's not unrealistic. But unfortunately, it's a real anchor when we try to move past where we've been and get to a new place.

For those officers who are out there doing a good job, I think the danger is that they will feel so beleaguered that they will choose either not to act when they should, which would be bad for society. Or they will decide that they don't want to be part of policing anymore because they don't want to be seen in that light, and we'll lose good police officers who are out there doing the right things.

I have no doubt we have lost and will continue to lose a lot of very good officers who will feel unappreciated or who will feel that they are very vulnerable to attack and just don't want to go to work every day with that possibility hanging over them.

I don't want to paint such a sympathetic picture for police officers in this regard that somehow, it would seem that I am neglecting or diminishing the real fears that so many people in this country have when they deal with the police. Those are very real fears, too.

If you look at use of force incidents with police-involved shootings here in San Antonio, for example, you will see that Black men are overrepresented for their population. And that's true also for Hispanic men."

The Solution: "I think when officers act badly, they should be held accountable for that, which means they should be punished for it. You know, we talk about holding people accountable without any definition of what that means, but it should have real consequences. Consequences that hurt.

We've got to somehow. Have people start looking at factual reality and get away from stereotypes, and that's a change in culture.

I think training is absolutely essential, but we're not going to train our way out of this.

Having taught in police academies in the past, I can tell you you can get through to some people with some messages, but you will never reach everybody. And it doesn't matter how many times you make them sit through the same course.

What you really need is a fundamental change in culture that would be more effective.

Within a law enforcement agency, you need all of the officers to be on board with this idea that we treat people as they should be treated. We don't resort to the use of force, any kind of or non-deadly force, unless it's really necessary. "