WAELDER, Texas — The pandemic gave many of us the chance to reflect on our circumstances -- and in many cases, our heritage and background.

For Lucille Contreras, it provided an opportunity to restore her connection with her Lipan Apache roots.

In a modern way, she's working to recreate the environment of her ancestors where they once lived in South Texas. This includes bringing the buffalo back to their native land.

As we close out Women's History Month, KENS 5 shares her story as part of our series: Together We Rise.

March 23 was a sunny and windy day in Waelder, Texas when we drove a little more than an hour to meet Lucille Contreras.

That Thursday happened to mark the two-year anniversary of living on her ancestral land.

"We are living on 77 acres with 15 head of bison, which we consider our relatives," said Contreras. "Our Lipan Apache group and communities, we are buffalo nation people."

Born and raised in San Antonio, Contreras built a career in IT.

In 2013, she committed to a seven-year focus learning about buffalo caretaking as a way of life. She lived on the Pine Ridge reservation in Porcupine, South Dakota, starting her own experience of rematriation.

"Rematriation is a movement right now across the United States, which we also call Turtle Island, where many tribal people, indigenous people across the land, are becoming closer to our own indigeneity in regards to food sovereignty, land access, land acquisition, caretaking of the buffalo as relatives," Contreras explained.

It was then, she created the non-profit Texas Tribal Buffalo Project as a pathway to come back home. The non-profit's mission is committed to healing the generational trauma of Lipan Apache descendants.

Contreras didn't return to Texas empty-handed. She brought back the gift of the buffalo. The first in the herd has genetics from Caprock Canyon, which is the state's herd. Named 'Bubbas', the male buffalo was gifted to Contreras by an anonymous donor.

The next three bison she acquired were females, born on a ranch in Carrizo Springs. Currently, Contreras has 14 female and 1 male bison on the land.

"Their scientific term is 'bison', but we as indigenous people have embraced and we claim the word 'buffalo.' Or, in Lipan Apache, iyanee," said Contreras.

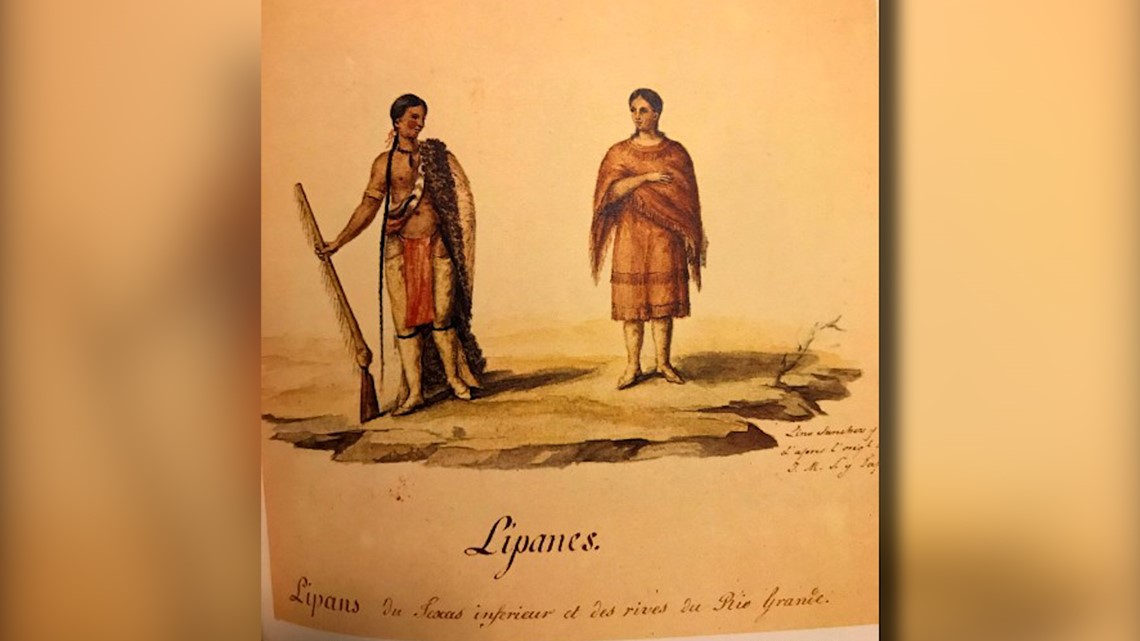

The Lipan Apache claimed Texas as home in the 1600's, the farthest east of all Apache tribes. When anglo settlers came to Texas in the early 1800's, the Lipan Apache welcomed them and traded bison, venison, hides, pecans and other staples. By 1880, smallpox, food shortages and war forced the tribe and its buffalo to scatter to avoid being hunted and killed.

According to the Texas Parks & Wildlife (TPW), between 30 and 60 million bison once roamed the North American plains. TPW estimates fewer than 1,000 head of bison remained in North America in 1888.

Contreras pointed to a map on display in her house that shows the immerse herds of bison lining the length of Texas.

"This is documented 1836," she explained.

Nearly two centuries later, on the Texas homeland of the Lipan Apache, the buffalo roam again -- treated with reverence.

"They survived generations. They survived massacres, decimation of their population. So did the indigenous people of Texas," said Contreras.

Right now, Contreras believes all 14 female buffalo are pregnant.

"People can come and feel the energy, feel the healing. Don't you just feel something special?" she asked, as we were sitting in her UTV, with the buffalo herd to our right. "They're medicine."

In May 2021, a ceremony was held on the land in Waelder which included an offering of a traditional bison harvest.

"There were approximately 100 Lipan Apaches here," Contreras recalled. "It was the first time in generations that Lipan Apaches were able to gather in safety without being persecuted, hunted or put through very traumatic situations."

Contreras purchased the Waelder property with a USDA Beginning Farmers and Ranchers loan. She's licensed to sell bison meat, which helps support programs for the Texas Tribal Buffalo Project.

Contreras says while there are other buffalo ranches in Texas, very few indigenous women are practicing the buffalo relative restoration and rematriation way of life.

"We're creating a sustainable model that hopefully can be replicated," she said.

When asked about the most challenging part of managing the buffalo, Contreras looked out to the mesquite on the land. She says the mesquite robs gallons of water and precious grass away from the buffalo.

"We could use some help in that," she explained. "The reason why Texas and other places really suffer with this overgrowth of mesquite is because the buffalo were taken away from this landscape. They were persecuted, they were hunted down. Buffalo are the best stewards of the land. They're the best caretaker of the land. They're a keystone species, but because that balance was disrupted that mesquite just grew to what you see today."

In early March, Contreras rallied in Washington, D.C. as lawmakers prepared to vote on the new farm bill.

Right now, only federally-recognized tribes have access to agriculture resources. Contreras is asking for a seat at the table.

"We do know that we are from here. We have our oral history and we're able to trace our roots back to this very land that we're standing on," said Contreras. "As indigenous people, regardless of federal recognition or not, we have every right to claim our own sovereignty."

There are three federally recognized tribes in Texas: Alabama-Coushatta, Kickapoo and Ysleta del Sur Pueblo.

During the summer, Contreras hosts summer camps at Texas Tribal Buffalo Project. There, children and families learn more about the Lipan Apache heritage and spend time among the buffalo.

She and her staff hope to begin planting USDA hemp in the near future, as the non-profit recently acquired their hemp license. They also secured two larger USDA grants to help them do work in food sovereignty. A feasibility study is underway for a meat processing facility at Texas Tribal Buffalo Project.

According to the Lipan Apache tribe's website, the current registered population of the tribe is about 4,500. Contreras is hopeful that with data decolonization, they will discover more of their brothers and sisters who are living among us.

March 3, the Biden administration announced a $25 million pledge to return bison back to tribal lands.