SAN ANTONIO — Students at Texas A&M University – San Antonio are spending the spring semester diving into the rich history of African American culture locally in collaboration with the San Antonio African American Community Archive and Museum (SAAACAM) via a grant with the city’s Office of Historic Preservation from the Summerlee Foundation.

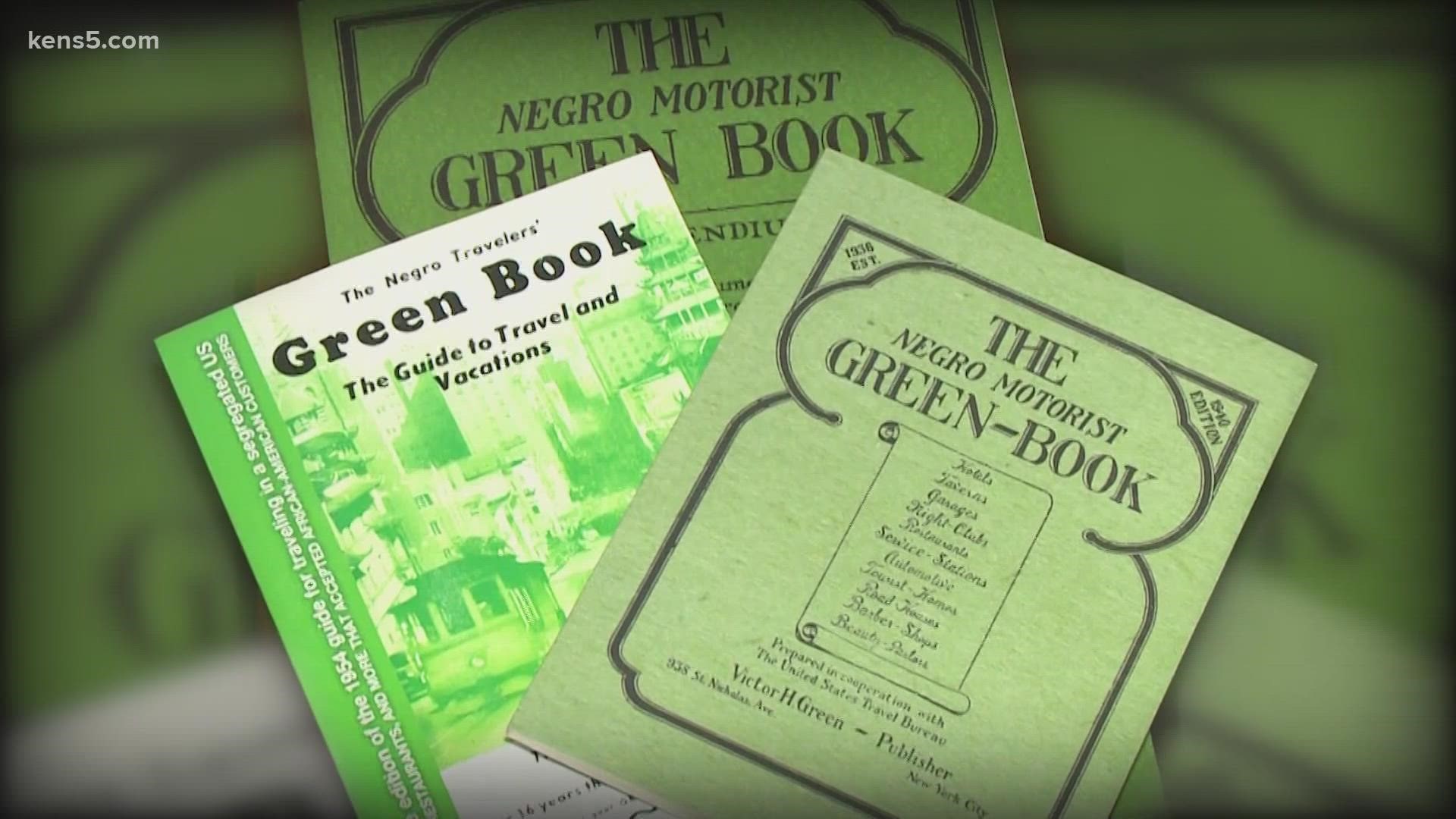

Thirteen undergraduate students in the Methods of Historical Research course are selecting one of more than 20 San Antonio locations originally listed in the Green Book to research. The book was first published by Victor Hugo Green of New York in 1936, and used to help Black motorists travel through the country during the Jim Crow era. By its 1939 publication, the green-colored guide book listed several safe places to eat, play and sleep in San Antonio, that would accept African Americans as customers.

The Green Book ceased publication after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. While the travel guide is no longer needed, many of the structures still stand today, and with a good look, can give visitors a glimpse of the harsh reality Black Americans faced in the segregation era.

“It was not safe to travel just anywhere and there were a lot of establishments that were segregated or off limits to African Americans. For many African Americans, they needed to know where was it safe to stop to eat or to stay at a hotel. They even wanted to know places to avoid like Sundown towns,” said Dr. Charles Gentry.

Dr. Gentry is a researcher with the UTSA Center for Sustainability , lecturer with the university’s history department and an advisor for SAAACAM. His lengthy resume matches his passion and knowledge on African American history in San Antonio.

In January, Dr. Gentry joined KENS 5 on a tour of some of the Green Book sites compiled by the UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures (ITC) in 2014. Our first stop was at 1605 East Houston Street, which was the home of Eason’s Service Station between the 1949 and 1956 editions of the Green Book, according to research.

“It’s now a vacant building but it’s the original structure that was a full service station that African Americans were welcomed to stop and get fuel when they were on the road,” said Dr. Gentry.

Our second stop was at Briscoe’s Beauty Shop at 515 South Pine Street, which now appears to be a private residential home. At its time of operation, the beauty shop was owned by William and Hattie Elam Briscoe. Dr. Gentry said cutting hair was Hattie’s specialty and she enjoyed sharing her passion with Black students at the cosmetology school where she also worked.

“She got into some trouble for being outspoken about segregation in the schools and lost her job. In the process of fighting to get her job back, she decided to study law,” he said.

Hattie became the first African American woman to graduate from St. Mary’s University Law School in San Antonio, and the only Black woman attorney in Bexar County for almost three decades.

Then, Dr. Gentry took us to site of the Ritz Motel on 2958 East Commerce Street. The original structure is no longer standing leaving the lot vacant with only a cement staircase and driveway. It’s a site Dr. Gentry admits researchers don’t have a lot of information on to this day.

“We are doing a lot of research to see how big was the Ritz Motel based on this foundation. We can see it was a pretty large property. There are a couple of driveways where there might have been parking and a couple of steps that may have led up to entrances or exits. We can imagine that there may have been a dozen sites depending the levels the motel may have been,” Dr. Gentry said.

Dr. Gentry said it’s likely more Green Book sites existed in San Antonio the three decades the book was used by Black motorists. In addition to his research, Deborah Omowale Jarmon’s mission is to document it as well. She is the CEO and director of SAAACAM.

“Our history is not written down so we are engaging the community to bring things to add to the history of African Americans in San Antonio,” said Omowale Jarmon.

The museum relies on the everyday historian to collect the unknown of the past and preserve it in their digital archive. Their exhibit at La Villita also includes the safe havens not listed in the Green Book like the former home of St. Phillips Episcopal Church, which is now St. Phillips College.

“A lot of information traveled by word of mouth so knowing that there was a school here, what that translated to if I was traveling and I needed to use the restroom, change clothes, or rest, going to a church like St. Phillips would give me that opportunity,” said Omowale Jarmon.

In May, the archives displayed at SAAACAM will go beyond the museum as the research students do this semester will be turned into historical markers.

“Deborah Omowale Jarmon wrote a grant that allowed us to partner with the Office of Historical Preservation to do alternative markers. [Black] history isn’t as public as many would like for it to be so my students are excited to get to know their community a bit more and uncover some of those places through research,” said Dr. Pamela Walker.

Dr. Walker is an associate professor of history at Texas A&M University – San Antonio. She will be guiding students to develop the markers, which will be created in the form of QR codes to place at the sites. Her students work will also be uploaded to the Special Collections Digital Library online so their articles can be accessible to anyone anywhere.

“It’s going to be challenging [for these students], but that’s what history is and we got to dig it up,” said Dr. Walker.

Continuing to dig up history to better understand the community in which we live.