SAN ANTONIO — Talk of slavery in the context of classroom instruction may come with controversy, fiery conversations, and incertitude. But a trip to Bexar County's Spanish Archives is a free and taxpayer-funded personal decision.

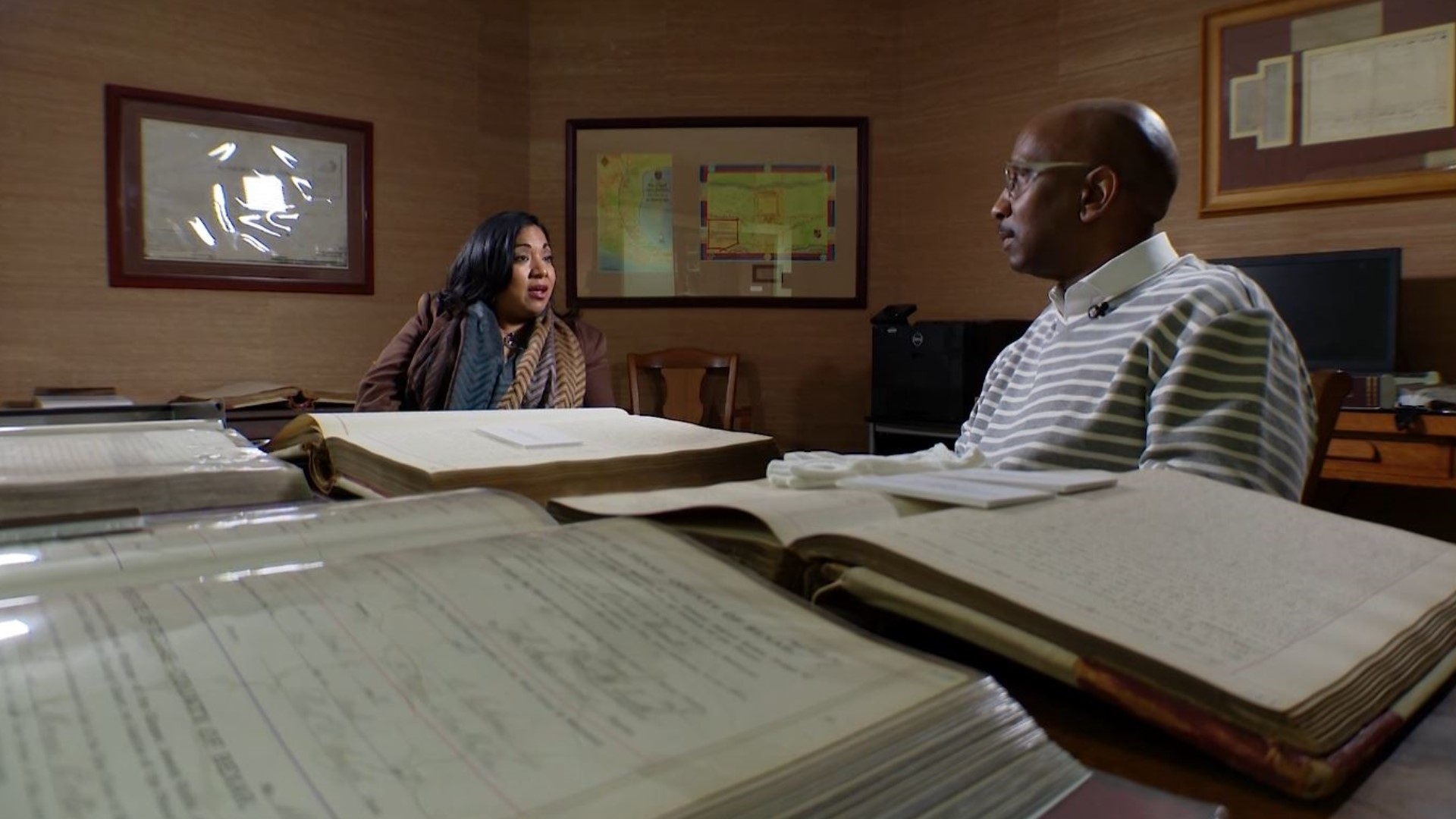

"The true history is written in every county clerk's book," Lucy Adame-Clark says.

Adame-Clark is the Bexar County clerk in charge of preserving the history some would embrace, and others would just as soon forget.

"The true history is that there was enslavement in Bexar County," she said. "The true history is that there was Native Americans in Bexar County. The true history is that they did enslave people where we're sitting at right now."

Adame-Clark says she received $18.5 million from real property land records to preserve that history. According to her, every county clerk in the state gets money from that pot.

60% of a vast collection is online now for the public to access. Adame-Clark said they have nursing certificates, historical election data, embalming certificates, probate records, deeds, real property and land records, criminal misdemeanor cases, well-protected health records due to sensitive information, census records, and more.

But the bills of sales for Black people are what get her choked up and teary.

"It was when I read the bill of sale: Negro woman healthy in body, to be delivered on so-and-so day. That stuck to me," she said. "I think because what we learned – what we heard – came to light in a book."

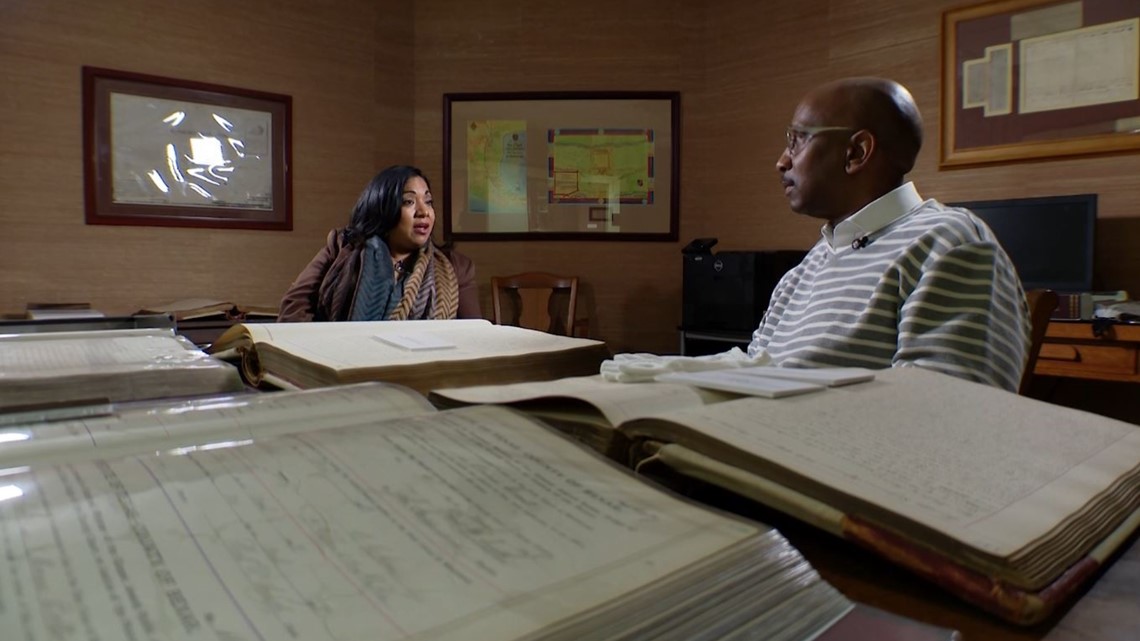

The transaction is one of hundreds from the Alamo City area, if not more. David Carlson, a county archivist who works for Adame-Clark, said seeing the purchases can be jarring.

"It startles people," Carlson said. "But we do have some bills of sale where people are being bought and sold as property."

He pointed to three purchases made on the same day in 1858 Bexar County. The sales were recorded in a county deed book in script, describing the arrangements.

Jenny was a 6-year-old with a lame foot, according to the book, who went for $200.

Lee, an enslaved 4-year-old boy, was also sold to the same man for the same price.

The purchaser bought teenage Henry for $500 to complete his shopping spree.

"I have cattle, and I felt like they were selling cattle," Adame-Clark said. "They sold them like cattle, and they were human beings."

According to Carlson, Blacks and Native Americans who looked Black were the only humans documented for sale.

"I think people tend to associate chattel slavery in Texas with east Texas. But there was always slavery internal to Bexar County," he said.

'They no longer become just names'

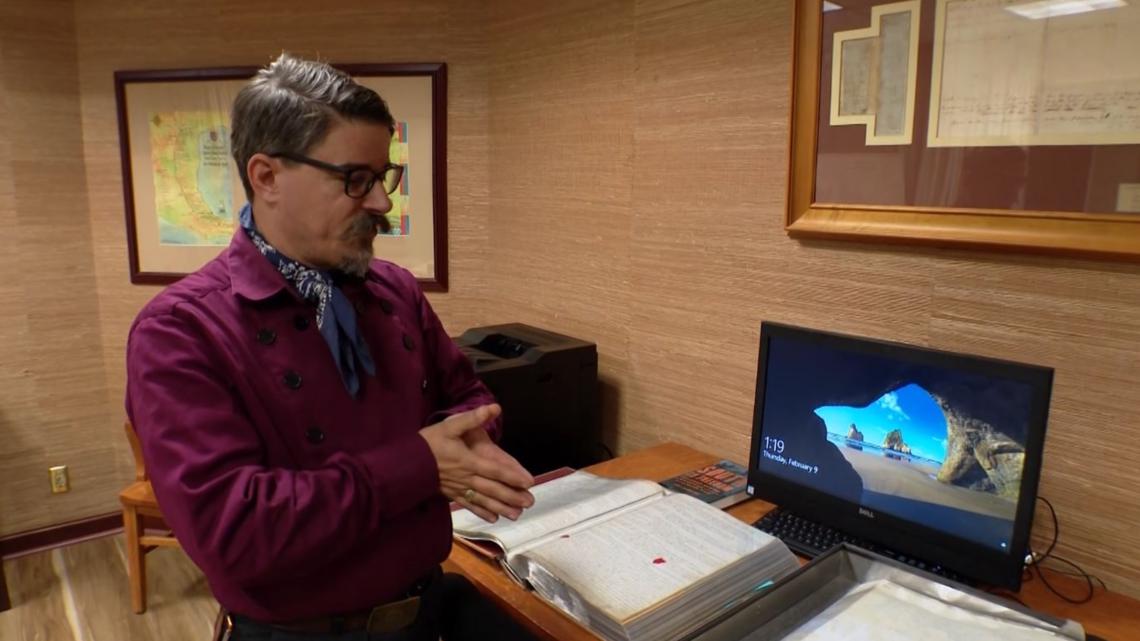

The archivist showed KENS 5 a map that designates a freedom colony near Von Ormy in their records, probate records with enslaved people that made a run for it to Mexico, the Black enclaves that would evolve into San Antonio's east side from Ellis Alley, and an 1870 federal census with free Black people seven years following the Emancipation Proclamation.

"There was a tendency at emancipation for some people to receive the surname of their former slaveholder," Carlson said. "Others rejected that, and they took other surnames. Some people, for example, chose the surname Freedmen."

Carlson said people engage history for different reasons, like researching an argument or a claim. Others want to verify passed-down stories and oral history.

"I could see them come to life. I could see the people. They no longer became just names," Lisa Jackson said.

Jackson, a San Antonio-based public relations professional, said digging into family history has made her a genealogist. Although tedious and expensive, the process infected her with the bug to search.

"Sometimes I feel like they were here with me, telling me, 'Go to that page,'" she said.

Jackson was able to dig into her family's east Texas history to find her lineage stretching back to her great-great-great-grandfather Peter Boales, his wife and their children.

In her family, she discovered Tuskegee Airmen, a marriage to a U. S. ambassador and a great-great-grandfather who, as a runaway slave, enlisted in the Union Army and was at Appomattox.

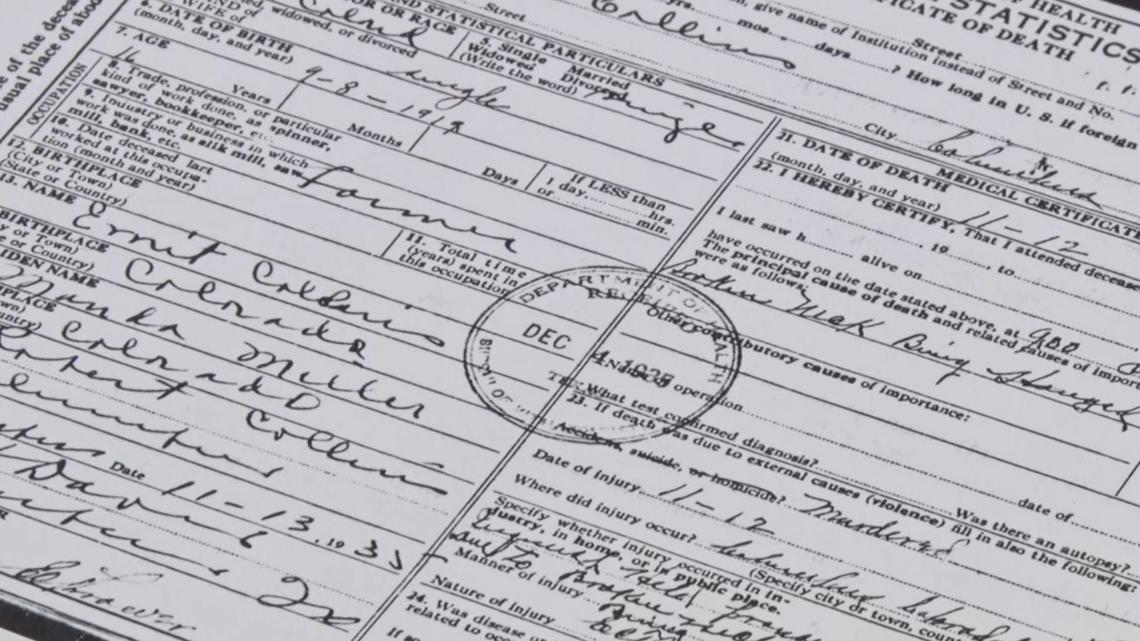

She also found the death certificates for two cousins lynched in Texas' Colorado County. Both were 16.

"They took photographs of the lynching, and they used to put them on postcards. So there's an actual photograph," Jackson said.

Reasons to remember

The depth of pain connected to the slave trade beyond is a part of history some want to move past, and don't find reliving the events necessary.

"Why would you not want me to know? It's not the question of why am I looking for the past," Jackson said. "The question is: Why don't you want me to know it?"

Adame-Clark, a San Antonio native, believes that acknowledging and trying to live above the past may be a solution.

"I am Latina. My father was treated at so many different levels... couldn't eat at certain restaurants," she said. But he instilled in us (the idea to) take something from it and be successful."

Jackson's reasoning is simple: It's history.

"But it happened," she said. "And if you are ashamed, that doesn't give you the right to keep me from knowing my past."

>TRENDING ON KENS 5 YOUTUBE: