DALLAS — In Allisa Charles-Findley’s phone, she still lists her brother as her emergency contact. He’s on her Netflix and Hulu accounts. She’s kept the voice mail from the hospital informing her of his death.

“These are things I just cannot delete,” she said.

Her late brother, Botham Jean, died Sept. 6, 2018, in a case that ignited a national controversy.

The 26-year-old accountant and St. Lucia native was shot and killed in his own apartment by Dallas police officer Amber Guyger as he ate a bowl of ice cream.

At her 2019 trial, Guyger testified that she believed – wrongly -- that he was an intruder in her own apartment.

She’d mistakenly parked on the wrong floor of the parking garage. She’d missed the signs she was at the wrong apartment, including his red floor mat.

But it was a malfunctioning door lock that ultimately allowed her to get in.

“It was an honest mistake made by her, and the fact that that door opened just added to the horrible confluence of events,” said Toby Shook, one of Guyger’s defense attorneys.

“I just thought, ‘How could somebody get killed in their own home by a police officer?”’ said prosecutor Jason Fine.

Jean’s death and Guyger’s trial would become a flashpoint in the frayed relations between police and the community.

Activists felt Guyger received special treatment. They were upset that she wasn’t immediately arrested, and that the then-head of the Dallas Police Association asked that a dash camera in a patrol car be turned off as he spoke to Guyger at the scene.

The association president “knew that she was about to consult with counsel,” Robert Rogers, another of Guyger’s attorneys, said. “No one was trying to cover anything up.”

Rumors ran rife -- particularly the one claiming there had been a romantic relationship between Jean and Guyger. It wasn't remotely true. The two didn’t know each other and Guyger had only recently moved into the complex.

“There was so much misinformation,” said prosecutor Mischeka Nicholson. “A lot of times it felt like we were fighting an uphill battle.”

The case strained the relationship between police -- many of whom didn’t think Guyger committed a crime -- and the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office.

“When you try a case, normally, law enforcement is our community partners, right? ...Unfortunately, they were not our community partners,” said LaQuita Long, another member of the prosecutorial team. “We were encountering obstacle after obstacle.”

Even lead investigator, Texas Ranger David Armstrong, testified outside the presence of the jury that he didn't think she'd committed a crime. He said he didn't think her actions were "reckless or criminally negligent based on the totality of the investigation."

The judge ruled that the jury couldn't hear Armstrong's opinions on the reasonableness of Guyger's actions.

When Guyger took the stand, she testified that she thought Jean was an intruder. “I thought he was going to kill me,” she said. “There was a loud yell. He was yelling, ‘Hey, hey, hey.’”

“She intended when she pushed the door open that she was going to go in and kill whatever that threat was,” prosecutor Mischeka Nicholson said. “And so, by her own words, it is murder.”

Guyger sobbed on the stand, saying, “I ask God for forgiveness, and I hate myself every single day.”

When it was their turn, prosecutors questioned her about why she didn’t use her emergency medical supplies. They pointed out that she had no blood on her uniform as evidence that she didn’t really try to help Jean.

They pressed her about the frantic text messages she sent to her former patrol partner within moments of shooting Jean, saying, “I need you. Hurry” and “I f...ed up.”’ They asked her about the sexually explicit messages she exchanged with her patrol partner in the hours prior to the shooting.

“You have to be able to show some sort of relationship in order to explain why she would be doing those things instead of helping Bo,” prosecutor Bryan Mitchell said.

But her team saw it as unfair and effort to “inflame emotions against her and bias the jury,” Rogers said.

Prosecutors argued that Jean was still seated on the couch when Guyger shot him. The defense attorneys contended he was coming toward her, lending credence to her belief that she was about to be attacked by an intruder.

“We believe that that she had a viable defense,” Rogers said. “We believe she had a valid defense for mistake of fact.”

Outside the courtroom, activists cheered when jurors found her guilty of murder. But they seethed when jurors returned with a 10-year sentence.

“The people were preparing to protest and riot,” Long said.

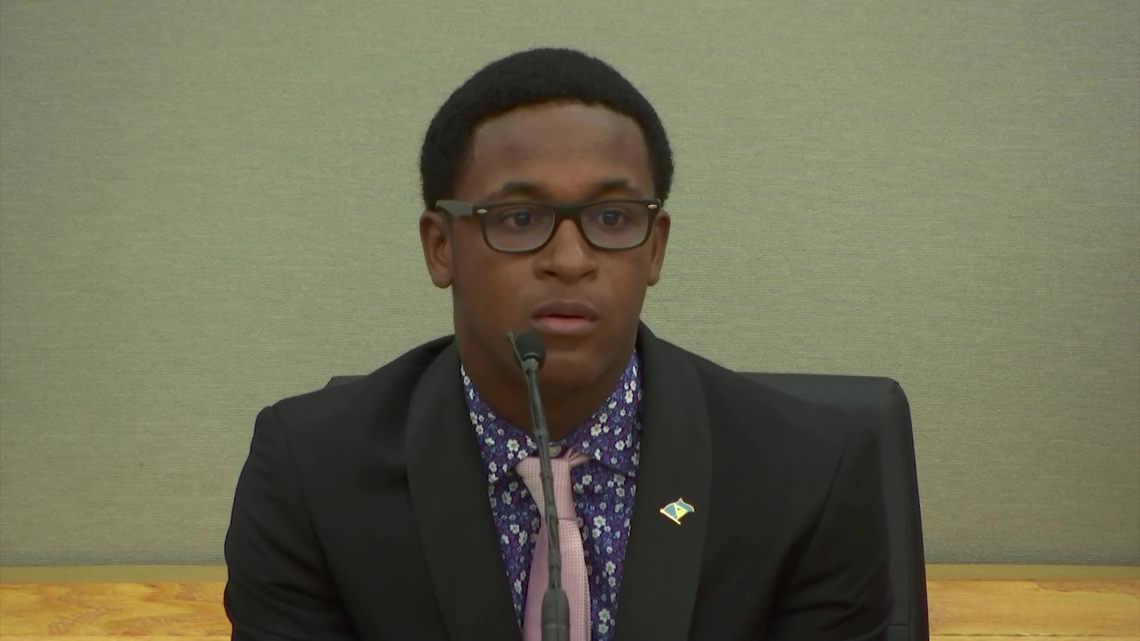

Brandt Jean, the victim’s younger brother, stayed silent before and during the trial.

Long, one of the prosecutors, said she asked Brandt Jean if he wanted to give a victim impact statement.

He turned her down.

But then he tapped Long on the shoulder and said he did want to speak directly to Guyger.

“I had no idea what was about to happen,” Long said.

Charles-Findley says she tried to make eye contact with him as if to tell him, “’Do you really want to do this? You don’t have to do this.’ I was trying to convey all that with my eyes.”

He spoke words no one expected.

“I wasn’t ever going to say this in front of my family or anyone but I don’t even want you to go to jail,” Brandt said. “I want the best for you. That’s exactly what Botham would want you to do and the best would be to give your life to Christ.”

He asked the judge, “I don’t know if this is possible, but can I give her a hug, please. Please.”

“The judge is looking at the bailiff, and the bailiff is looking at the judge, and I'm looking at Toby, and none of us knows,” Rogers recalled. “There's not a playbook for that in the code of procedures.”

Kemp responded with one word, “Yes.”

Guyger and Brandt Jean hugged each other several times as Guyger sobbed.

“You expect the blow ups, the attacking and that sort of thing,” Mitchell said. “What you don't expect is … I want to hug this person, and tell her that it's okay and I forgive her.”

That moment seemed to quell the angry crowd in the hallway.

“It’s not how I felt, but I’m proud of him,” Charles-Findley said.

She says she shielded him from the many emails, phone calls and social media posts from people angry that he had offered forgiveness to his brother’s killer.

“He was not doing this for anybody else, or even for Amber Guyger,” she said. “He was doing it for himself.”

It wasn't the only unprecedented moment. Kemp, after embracing and speaking with Jean’s family, spoke to Guyger. Then she left the courtroom and returned with a Bible. She opened the book to John 3:16, and told her, “You start with this.”

Guyger embraced Kemp. The judge returned the hug.

“You haven’t done so much that you can’t be forgiven,” the judge told Gugyer. “You did something bad in one moment in time. What you do now matters.”

In reflecting on the jury’s decision to give Guyger’s a ten-year sentence, Mitchell said, he couldn’t help but think there was some “discussion about what would Botham do if he was sitting back here.”

The penalty range was five to 99 years.

“The jury's responsible for considering that full range,” Fine said. “It's not really fair to be like, ‘Oh, they got it right in terms of convicting him of murder … and then be like well the same jury, they’re just totally wrong in the 10 years.”

Since Guyger began her sentence, her attorneys told WFAA that she’s been in protective custody and spends much of her time reading and studying the Bible, and availing herself of educational opportunities.

“She's very remorseful about what happened, and she's proven that she could be productive citizen,” Shook said. "She just wants to be able to rebuild her life whenever she's released.”

Members of the prosecution team have stayed in contact with the family. Long and her family visited the Jeans in St. Lucia while on a cruise.

The family filed lawsuits and settled for an undisclosed amount with the apartment complex and the maker of the malfunctioning lock earlier this year.

The Botham Jean Act became law in 2021. It requires officers to wear body cameras to keep them turned on when an investigation involves them.

The family will be in town this month for the annual gala for the foundation named in his memory. The nonprofit funds are earmarked for programs for at-risk youth.

The federal civil rights lawsuit the family filed against Guyger is set for trial later this year. Guyger’s eligible for parole Sept. 29 -- her late brother’s birthday.

“I don't know if it is some higher power at work…,” Jean’s sister said. “It has to be. If not, it would just be a cruel joke.”

Charles-Findley says she wrote Guyger a letter in 2021 asking if she would come to see her. She did not hear back.

“I wanted her to look me in my eyes and tell me exactly what happened,” she said. “What were his last words? Was he scared? I just have so many questions for her.”

Jean’s sister said the family wonders what Botham’s life would be like today.

“I see all his friends, especially his college friends, celebrate their milestones, their weddings and their birth announcements," she said, "and I always wonder how it would be for Botham."