MEXICO CITY, Mexico — Mexican authorities are trying to identify two bodies found in the Rio Grande, including one along the floating barrier that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott had installed recently in the river, across from Eagle Pass, Texas.

Mexico's Foreign Relations Department first reported that a body was found along the buoys between Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras, Mexico, on Wednesday evening, and immediately connected it to the risks Mexico had warned of before the barrier was installed. Hours later it said another body had been found 3 miles (5 kilometers) upstream in an area where there are no buoys.

Both bodies were recovered by Mexican authorities, and the Coahuila state prosecutor's office was working to identify them and determine the cause of death.

Mexico said the Texas Department of Public Safety had advised its consulate of the body along the floating barrier. Texas said it notified Mexico after receiving a report of a body upriver from the barrier Wednesday. It was unclear if that was the body that ultimately ended up lodged against the buoys.

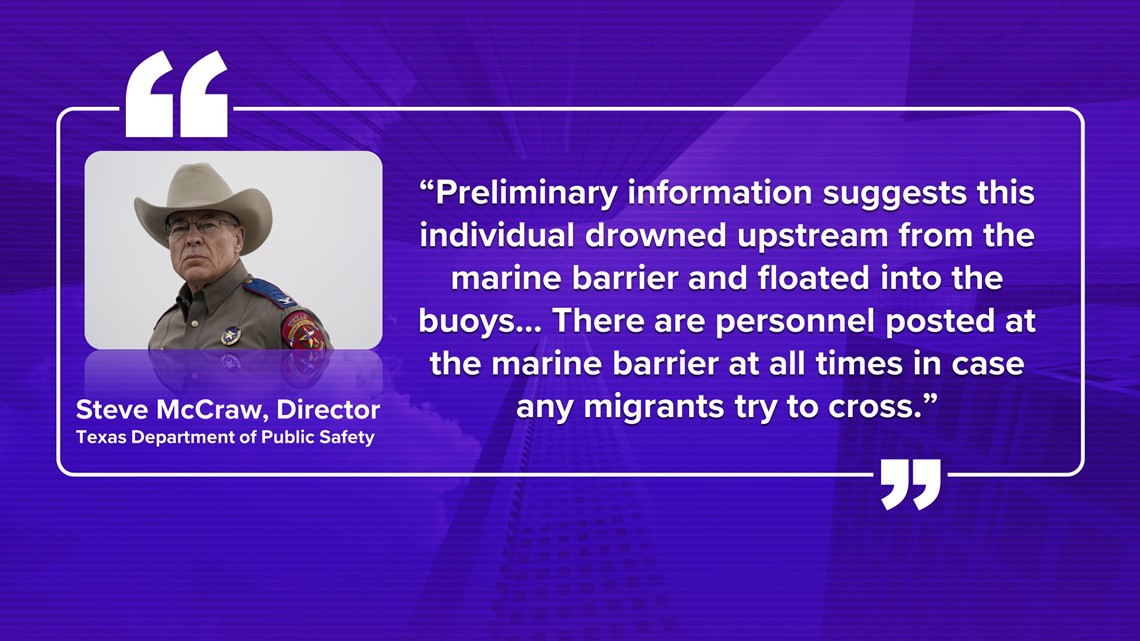

“Preliminary information suggests this individual drowned upstream from the marine barrier and floated into the buoys,” said Steve McCraw, the DPS director. “There are personnel posted at the marine barrier at all times in case any migrants try to cross.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection was asked by an email and a phone call for comment on the situation, but had not responded.

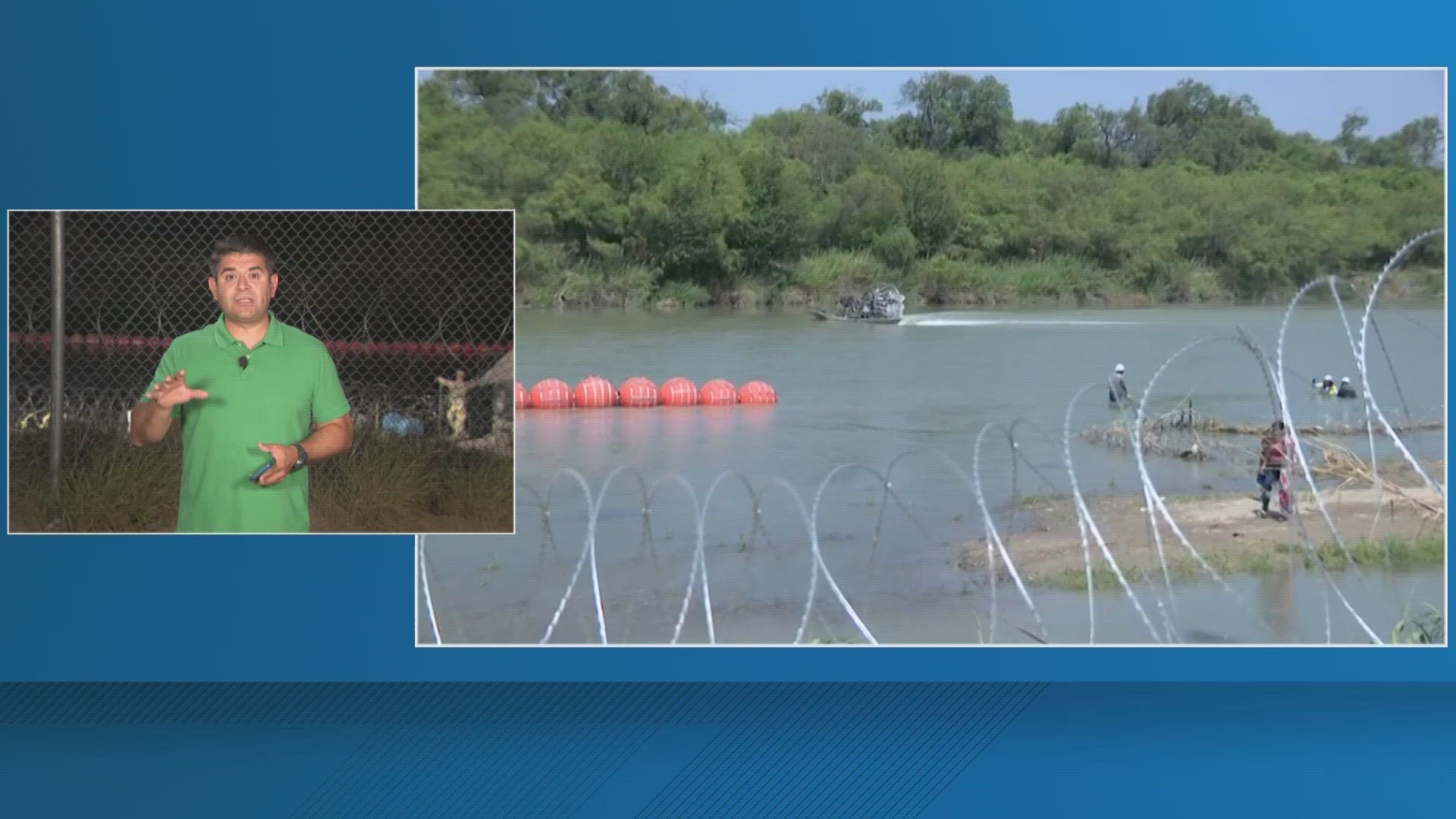

Mexico and others have warned about the risks posed by the bright orange, wrecking ball-sized buoys put on the Rio Grande in an effort to make it more difficult for migrants to cross to the U.S. The Foreign Relations Department also contends the barrier violates treaties regarding the use of the river and Mexico’s sovereignty.

“We made clear our concern about the impact on migrants' safety and human rights that these state policies would have,” the department said in its statement Wednesday night.

Andrew Mahaleris, spokesman for Abbott, said in a statement Thursday that “the Mexican government is flat-out wrong.” He said preliminary information indicates the person drowned before coming near the barriers.

He said the Texas Department of Public Safety previously reported to U.S. immigration agents that there was a body floating upstream from the barriers in the Rio Grande.

Mahaleris said Texas officers monitor the barriers and have not observed anyone attempting to cross since they were installed. “Unfortunately, drownings in the Rio Grande by people attempting to cross illegally are all too common,” he said.

The barrier was installed in July, and stretches roughly the length of three soccer fields. It is designed to make it more difficult for migrants to climb over or swim under the barrier.

The U.S. Justice Department is suing Abbott over the floating barrier. The lawsuit asks a court to force Texas to remove it. The Biden administration says the barrier raises humanitarian and environmental concerns.

The buoys are the latest escalation of Texas’ border security operation that also includes installing razor-wire fencing and arresting migrants on trespassing charges.

Migrant drownings occur regularly on the Rio Grande. Over the Fourth of July weekend, before the buoys were installed, four people, including an infant, drowned in the river near Eagle Pass.

Isabel Turcios, a nun who runs the Casa del Migrante shelter in Piedras Negras, said migrants continue crossing the river there even though authorities put razor wire under the bridge connecting the two countries and the buoy barrier a little farther downstream.

She said they typically cross under the bridge where the river is more shallow and then walk downstream to an opening in the razor wire. She said she didn’t know if people still tried to cross where the buoys were installed downriver.

“Tons of migrants are still arriving,” Turcios said. “Last night some 200 people slept (at the shelter). This morning 50 more have entered the shelter."

She said many migrants decide to cross because they feel it takes too long for U.S. authorities to process applications to enter the U.S. legally.

She said her shelter was receiving a lot of Venezuelans, in many cases mothers with children, who stop only briefly to bathe, rest and then try to cross the river.