Waving a copy of the Ten Commandments and a 17th-century textbook, amateur historian David Barton recently argued that Christianity has always formed the basis of American morality and thus is essential to Texas classrooms.

“This is traditional, historical stuff,” he told a Texas Senate Education Committee last month. “It’s hard to say that anything is more traditional in American education than was the Ten Commandments.”

For nearly four decades, Barton has preached that message to politicians and pews across the country, arguing that church-state separation is a “myth” that is disproven by centuries-old texts, like the school book he showed senators, that reference the Ten Commandments and other religious texts.

Now, Barton’s once-fringe theories could be codified into Texas law.

Emboldened by recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions and the growing acceptance of Christian nationalism on the right, Barton and other conservative Christians could see monumental victories in the Texas Legislature this year.

Already this legislative session, the Texas Senate has approved bills that would require the Ten Commandments to be posted in all public school classrooms and allow unlicensed religious chaplains to supplant the role of school counselors. Meanwhile, there are numerous efforts to eliminate or weaken two state constitutional amendments that prohibit direct state support of religious schools and organizations, a key plank of the broader school-choice movement.

In legislative hearings, lawmakers have called church-state separation a “false doctrine," and bill supporters have blamed it for school shootings, crime and growing LGBTQ acceptance.

In Texas, they believe they can create a national model for infusing Christianity into the public sphere.

“We think there can be a restoration of faith in America, and we think getting Ten Commandments on these walls is a great way to do that,” former state Rep. Matt Krause testified last month. “We think we can really set a trend for the rest of the country.”

A new legal and political landscape

It's the latest battle in what Barton and other Christian leaders have framed as a long-running and existential war with the secular world, rhetoric that has helped fuel Republican movements to crack down on LGBTQ rights, ban books, push back against gun control and limit the teaching of American history in classrooms, among other oft-framed "culture war" issues.

And it comes amid growing acceptance on the right of Christian nationalism, the belief that the United States’ founding was ordained by God and, thus, its laws and institutions should favor Christians.

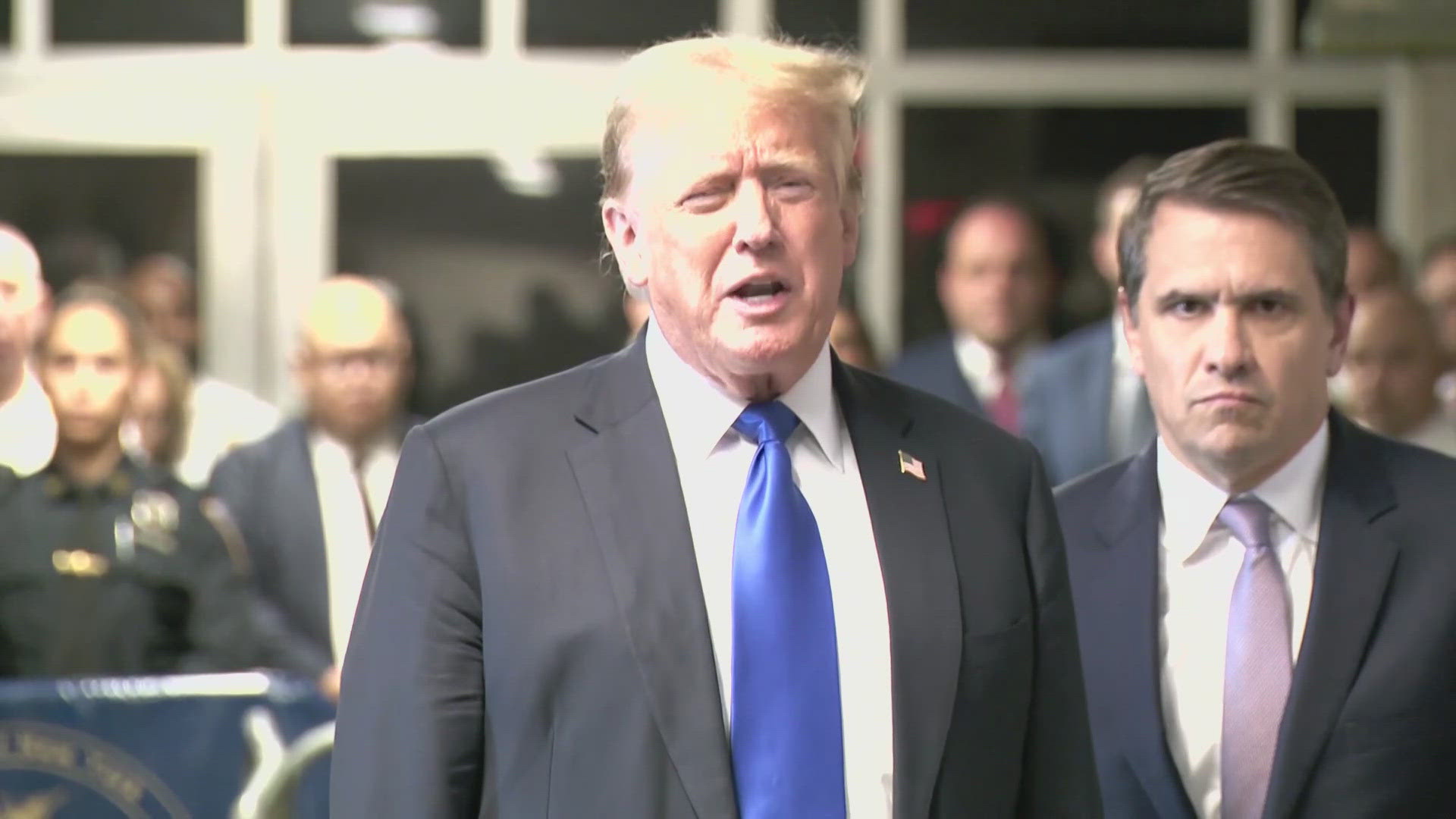

Bolstered by former President Donald Trump — who shored up evangelical support through his vow that “Christianity will have power” under his leadership — and animated by a rapidly secularizing and diversifying society, Christian nationalist movements have become mainstream among large factions of the Republican Party.

February polling from the Public Religion Research Institute found that more than half of Republicans adhere to or sympathize with pillars of Christian nationalism, including beliefs that the U.S. should be a strictly Christian nation. Of those respondents, PRRI found, roughly half supported having an authoritarian leader who maintains Christian dominance in society. Experts have also found strong correlations between Christian nationalist beliefs and opposition to immigration, racial justice and religious diversity.

Texans have been key drivers of that ideology, experts say.

“The nation has started to become conscious of Christian nationalism within the last handful of years,” said David Brockman, a nonresident scholar at the Religion and Public Policy Program at Rice University’s Baker Institute. “But we’ve been pretty much under the thumb of Christian nationalism here in Texas for at least a decade.”

He notes that Texas is home to a litany of well-known purveyors of Christian nationalism or related ideologies, including BlazeTV founder Glenn Beck; U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz’s father, Rafael Cruz; and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who has called the United States “a Christian nation” and said “there is no separation of church and state. It was not in the constitution.”

“We were a nation founded upon not the words of our founders, but the words of God because he wrote the Constitution,” Patrick said last year.

Such claims have been elevated by a cadre of far-right financiers who have shoveled small fortunes into political campaigns and institutions that seek to erode the wall between church and state, including through candidates for the State Board of Education and local school boards.

Those efforts have found an avid audience within the state’s massive evangelical — and mostly white — conservative voting bloc and have been routinely amplified by Texas megachurch pastors who’ve made no bones about politicking from the pulpit, even after others have said they’re running afoul of restrictions on political activity by tax-exempt nonprofits.

A 2022 Texas Tribune and ProPublica investigation found that at least 20 churches in Texas may have violated such rules. Among them was Mercy Culture Church in Fort Worth, which has hosted Kelly Shackelford — whose First Liberty Institute has been instrumental in legal challenges to the separation of church and state. Krause, the former Texas representative who testified last month in support of the Ten Commandments bill, recently took a job at First Liberty Institute after a decade in the Texas Legislature.

On Sunday, Krause’s successor, state Rep. Nate Schatzline, also spoke at the church.

“The devil is not afraid of a church that stays within the four walls,” Schatzline said before touting a wave of successful conservative candidates in Tarrant County and anti-LGBTQ bills he’s supporting in the Legislature. “That’s what happens when the church wakes up. That’s what happens when men and women of God get behind other men and women of God.”

Founding fathers: A wall of separation

But few figures have been as instrumental in the push to erode church-state separation as Barton, a self-taught historian who founded his group, WallBuilders, in 1988 with a mission to “present America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on the moral, religious, and constitutional foundation on which America was built.”

Barton served as vice chair of the Texas GOP from 1997 to 2006 and has pushed back for decades against conventional interpretations of the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which prohibits the government from establishing a state religion. Barton argues the “wall of separation” that the Founding Fathers envisioned has been misconstrued. In his view, that separation was only meant to extend one way, protecting religion — ostensibly, Christianity — from the government, not vice versa.

“‘Separation of church and state’ currently means almost exactly the opposite of what it originally meant,” his group’s website claims.

Among Barton’s favorite tactics: citing centuries-old texts, such as the one he presented to the Texas Senate committee, that he says mention Christianity or the Ten Commandments. That, he says, suggests a longstanding Judeo-Christian influence on American education, law and morality. Abandoning those universal moral standards, he and other WallBuilders leaders claim, helps explain most of America’s ills — including the recent mass shooting at a Nashville, Tennessee, Christian school.

“Our young people are having a very hard time determining what’s right and wrong,” David Barton’s son, Timothy Barton, told the Senate committee last month. “We’re seeing people do what they think is right. But what they think is right is often things like what resulted in Nashville. … Instead we should be presenting those morals [in the Ten Commandments] in front of students so they know there is a basis of morality and killing is always wrong.”

Barton’s broader theories have been widely ridiculed and debunked by historians and other scholars who note that he has no formal historical training and that his 2012 book, “The Jefferson Lies,” was recalled by its Christian publisher because of factual errors.

Even so, he’s been courted by political hopefuls, including Cruz, and his theories have been routinely elevated by others in the Texas GOP.

In just one hearing last month, state Sen. Donna Campbell, R-New Braunfels, praised one of Barton’s books as “great”; Sen. Mayes Middleton, R-Galveston, called separation of church and state “not a real doctrine”; and Weatherford Republican Sen. Phil King brought forth Barton — an “esteemed” witness — to support King’s bill to post the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms.

Such a proposal, King said, would not have been feasible a few years ago.

“However, the legal landscape has changed,” he added.

A “massive shift” in the law?

King has a point.

In 2022’s Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of a Washington state high school football coach who argued that his religious rights were violated because his employer, a public school, sought to limit his practice of silently praying in the middle of the football field immediately after games. The district had asked Kennedy to pray at a later time to avoid the appearance that the school was endorsing his beliefs, then declined to renew his contract after he refused to do so.

In a 6-3 ruling, the court’s conservative supermajority said Kennedy’s prayers were protected by the First Amendment, rejecting the district’s contention that allowing the prayers amounted to an official endorsement of religion.

The ruling dealt a substantial blow to the so-called Lemon test. Established by the court’s 1971 decision in Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Lemon test held that the government could interact with religion so long as it served a secular purpose, did not advance or inhibit religion, and did not create an excessive government entanglement with religion.

In the Kennedy decision, the Supreme Court also ruled that restrictions on religious expression must take into account historical context and practices — a directive that some have taken as a green light to put religion in the classroom, including Krause and First Liberty Institute, which represented Kennedy.

“The law has undergone a massive shift,” Krause said during his testimony in support of the Ten Commandments bill. “It’s not too much to say that the Kennedy case for religious liberty was much like the Dobbs case was for the pro-life movement. It was a fundamental shift.”

Experts aren’t yet sold on that claim.

“Anyone who tells you that the law in this area is clear, or has ever been clear, is probably trying to sell you something,” said professor Steven Collis, director of both the First Amendment Center and the Law and Religion Clinic at the University of Texas at Austin.

While Collis added that the Lemon test was often ignored or disputed by courts because of its vague language, he said the Kennedy ruling neutered much of it, as well as the government’s ability to limit religious expression based on claims that doing so amounts to a state-sanctioned endorsement of religion.

But Collis noted that part of the Kennedy ruling was predicated on the idea that the coach was not forcing players to pray with him, an important distinction to the court’s majority. He said there’s a case to be made that posting the Ten Commandments or other religious texts in a classroom — where children are required to remain — is far different. And he expects such legislation would face court challenges in which opponents say that it amounts to a “coercion of religion upon students.”

“There has been a long tradition in the United States of saying, whatever government is doing, it has to do neutrally between religions — it can’t treat one religion differently than another. And certainly, it can’t favor one religion over another,” he said. “One of the challenges with having something like the Ten Commandments up in a public school — or really any religious texts up on the wall in a public school — is you immediately have to ask the question, whose religion is it going to be?”

Non-Christian Texans are voicing similar concerns. In the Ten Commandments bill, they see a backlash to the growing diversity and religious plurality of Texans, and say it’s discriminatory for the state to elevate one faith while ignoring many others.

“We are extremely disappointed,” said Rish Oberoi, Texas director for the civic group Indian American Impact. “Texas has an incredibly diverse population that includes Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and others. We’ve created an environment that has drawn people from all over the world to places like Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio. And it’s depressing to see that our leaders and our legislators do not seem to acknowledge how much we contribute culturally, politically and civically to this state.”

Rulings embraced by school choice advocates

A potential legal challenge to the Ten Commandments or a similar bill would come amid a broader shift in how the U.S. Supreme Court and some state legislatures treat religious expression.

The series of moves has deeply concerned advocates for church-state separation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, Congress made the historic decision to let religious organizations — including some of the nation’s largest and most influential congregations — receive forgivable federal disaster loans.

In 2021, Texas lawmakers passed legislation that required donated “In God We Trust” signs to be placed in public classrooms. Not long after, a North Texas school district rejected signs in Arabic that were donated by a local parent while allowing English versions that were provided by Patriot Mobile, a Grapevine-based conservative cellphone company that has funded numerous Christian nationalist campaigns in the state, including anti-LGBTQ school board candidates.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court, driven by its conservative majority, has handed down a series of consequential rulings that have raised questions about so-called Blaine amendments in 37 state constitutions, including Texas’, that prohibit or limit state funding of religious institutions, including schools:

- In 2020, the court ruled 5-4 in favor of a Montana woman, Kendra Espinoza, who argued that her state’s Department of Revenue improperly barred her from using a tax-credit scholarship at a Christian school.

- In 2022, justices similarly ruled that Maine could not bar religious institutions from public funding, a significant decision to ongoing debates over public education financing in Texas.

Those rulings have been embraced by the broader school choice movement.

The same week that state Sen. Brandon Creighton, R-Conroe, filed Senate Bill 8 — a massive overhaul of the Texas educational system that would allow religious schools to receive state funding via educational savings accounts — he requested an expedited opinion from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton about whether the state’s Blaine amendments were unconstitutional.

Days prior, state Sen. Angela Paxton — a McKinney Republican who is married to the attorney general — filed legislation that would repeal “the constitutional provision that prohibits the appropriation of state money or property for the benefit of any sect, religious society, or theological or religious seminary.”

The next week, the attorney general released an opinion that said Texas’ Blaine amendments violated the U.S. Constitution’s free-exercise clause.

There are also two bills, one in the House and one in the Senate, that similarly challenge the state’s Blaine amendments.

Catholic groups have decried the Blaine amendments as discriminatory because they were often rooted in anti-Catholic bigotry. And they reject the notion that removing them — or allowing public funding for religious schools — would erode church-state separation.

“There’s nothing in these bills where the state is establishing religion. And there’s no separation of church and state issue because the state [already] funds religious ministries and religious organizations,” said Jennifer Allmon, executive director of the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops.

“If you have a Catholic hospital or a Baptist hospital, they can bill Medicaid for their health care services, even though their health care services are an extension of the healing ministry of Jesus Christ,” Allmon said.

Church-state separation groups disagree.

Amanda Tyler is executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, a Washington, D.C.-based group that advocates for a strong wall between government and religion. While Tyler agrees that some Blaine amendments can be traced to an 1875 proposal by U.S. Rep. James G. Blaine — who was clearly anti-Catholic — she argued that other provisions, which she calls “no-aid” clauses, predate Blaine’s tenure and preserve, instead of diminish, religious freedom.

Removing those restrictions — particularly as the United States continues to diversify and secularize — would be disastrous, she said.

“The principle behind the original ‘no-aid’ principle was not picking and choosing among different religious groups, as it applies equally,” Tyler said. “We can shun bigotry without throwing away that principle, which has served religion well in this country for centuries, leading to greater religious flourishing and pluralism.”

The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

>MORE TEXAS POLITICS NEWS: