MCALLEN, Texas — Passing the historic Cine El Rey in the heart of McAllen, Texas on Wednesday, you wouldn't have noticed the marquee advertising that evening’s live comedy attractions, nor the next movie showings.

Instead, Owner Bert Guerra posted the message: “WELCOME TO MCALLEN, 7TH SAFEST CITY IN AMERICA.”

That welcome isn’t just for tourists. President Donald Trump is expected to make his first visit to the Rio Grande Valley on Thursday to address what he has referred to in recent weeks as a humanitarian crisis unfolding along the border. But talking to Guerra and others who live in McAllen, the surrounding communities, and the regions of northern Mexico that sit just a few miles south, people here in the community say that if there’s indeed a crisis, they haven’t experienced it.

“I wanted people to have a conversation,” Guerra said. “I’d rather have people talk about things than have people fight about things. When you have someone like the president at the helm of information slanting the truth so much, it makes it the norm.”

His declaration that this city really is the seventh safest in the country may be a little outdated. Guerra attributes the statistic to a report from a few years ago by SmartAsset, a financial technology company.

The company’s 2018 update listed McAllen as the 11th safest—a slight drop, but still no small feat.

Local crime has actually dropped over that span. According to annual reports by the McAllen Police Department, the total number of reported crimes dropped by 31 percent between 2011 and 2017, from 6,120 total crimes to 4,214.

And though the 2018 numbers have yet to be finalized, local officials proudly reminded the city’s 41,000 Twitter followers on Wednesday morning that it is still one of the state’s safest cities.

It’s a trend that many locals who have lived here for years or decades have noticed, and say they are proud of. It’s also an attribute of their community that has led them to ask: What crisis?

'It won't stop anything'

Here in McAllen, where 85 percent of the population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, diversity isn’t just normal. It’s a way of life. Signs advertising zapatos, juguetes and tortas adorn many storefronts, the owners of which say they rely on the business of those living just across the border in Reynosa.

Some go even further, saying that the community couldn’t survive without the consumerism of Mexicans who routinely (and legally) cross the border.

“There’s a lot of people here that work and have been working here for years that have built McAllen,” said Kathia Meza, who lives in Dallas but says she has been coming to McAllen all her life.

Just as crossing back-and-forth on the McAllen-Hidalgo International Bridge is routine, so too are sightings of illegal crossings. There's already border fencing along some stretches of land here, steel slats and bollards in others. That hasn't stemmed the flow of illegal crossings. It’s a fact of life in the Rio Grande Valley, as many residents here will attest to.

But most residents here say they don’t believe a fortified wall, even one that's taller and made entirely of concrete or steel, would fix the problem.

“Mexicans will find a way to cross that wall,” Meza said. “That’s a waste of money and work, and it won’t stop anything. It’s a waste of money that they can be using for other things.”

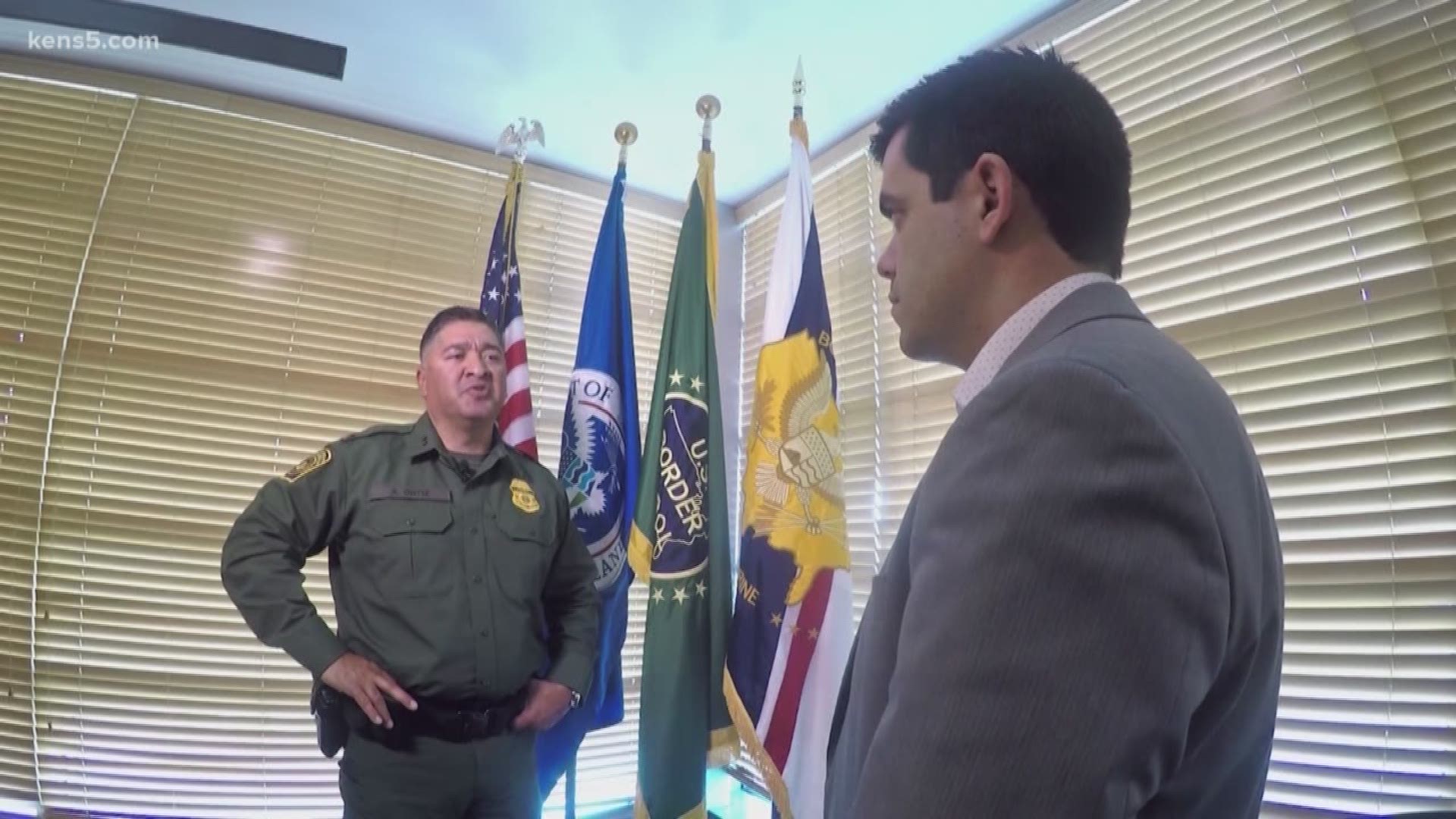

Residents in McAllen say those “other things” could indeed go toward fortifying border security, suggesting that the Border Patrol could be bolstered or more technologically-savvy methods undertaken to survey the U.S.-Mexico border.

Carlos Reyes owns a shoe store in McAllen with his wife and has lived here for about two years. He was one who suggested some ideas of his own for where to allocate the $5.7 billion the Trump administration says his would cost.

“I would prefer that, with that money, they help with other causes, like health or education. Instead of a wall, hire more agents,” Reyes said. “A wall dividing two nations that have geographically always been united will look bad.”

To many residents – a lot of them residents here for their whole lives – “crisis” is an inaccurate portrayal of their community and the Rio Grande Valley. Some of them say the real crisis is unfolding all across the country, and has been for nearly three full weeks.

“The crisis is what he’s putting us through—the government shutdown,” said Benny Herrera, another Rio Grande Valley lifer. “That’s a crisis.”

Doris Lugo, a 30-year resident of McAllen and the owner of Doris' Snacks, agrees that the situation at the border "isn't necessarily a crisis." In fact, she says it's the tight-knit community that gives her a strong sense of security.

"I know everybody, and everybody knows me," she said. "And if someone is new to town, I'll get to know them."

She's more or less a living embodiment of the sense of community that pervades McAllen and the Rio Grande Valley at large; a proud resident for whom you get the sense things would have to get real bad before she even thought about leaving.

That's a part of the region's personality she said she hopes Trump observes in his visit on Thursday, his first to the Rio Grande Valley.

“He knows what he wants to see, what he will need to see to make his decisions," Lugo said. "But I hope, more than anything, he notices the community."

Not a wall, but maybe something else

There are shades of complexity in the debate, however, even here in blue-tinged Hidalgo County that voted for Obama in 2012, Clinton four years later and O’Rourke two months ago. No one denies that immigrants from Mexico and Central American are illegally trying to make their way into the United States; they might just see a different way of fighting the issue.

Joe Escamilla, who on Wednesday could be found working at the McAllen sports store he helps to manage, and who once came across an illegal migrant lost in the area after separating from his group, suggested reform elsewhere.

“Within the people who are allowed to come in, there are bad people. And they come in because the United States makes it easy for them sometimes to come in and be granted asylum and they can live here for a free handout,” he said. “And being from the valley, that bothers me.”

Escamilla soon added, as a footnote: “It’s not a crisis.”

It’s a sentiment with many echoes in the area. Residents say they don’t necessarily feel any less secure or safe living so close to the border, insofar as living in a post-9/11 world has brought new focus to bolstering security.

"Times have changed. Things aren’t safe anymore, 9/11 proved that," Escamilla said. "It showed we have to protect ourselves.”

But safety here isn't a worsening issue. Thanks to the efforts of McAllen Police this decade, the opposite is actually true. And Mexicans who legally walk across the border to visit friends or shop at southern Texas stores will be the first to say Hidalgo County feels safer than Reynosa.

“The quality of life is much better here too,” said Argelia Aparicio, who has lived in Reynosa for about two decades. “We come to shop and we go back. We don’t feel danger. If there’s a wall, nothing would change for me.”

The same goes for most of her neighbors, who aren’t oblivious to illegal border crossings themselves. For them, even if a wall is constructed, they’ll still cross back and forth. It’ll be business as usual, with their visas in hand.

But even they don’t see construction of a wall as a solution.

“(Illegal immigration) doesn’t justify the wall because people are still going to find ways to cross. If they construct the wall, people will cross where they can. It won’t fix the problem,” said Helacio Martinez, who crosses weekly to shop.

But even in a blue Texas county there are splashes of red. Cristina Garfield, a member of Hidalgo County Young Republicans born and bred in the RGV, had no issue agreeing with Trump that what's unfolding along the border constitutes a crisis.

For her, it's been a crisis for a long time.

"The fact that...the president realizes it's a real issue, it's very refreshing to get that kind of one-on-one attention," she said, adding that she supports the idea of a fortified wall as a "buffer zone" between the Rio Grande, itself already a natural barrier, and the first Texas towns immigrants would arrive at.

Garfield's stance is a reminder that there isn't a place where one perspective reigns unanimously. But for the grand majority in this southern Texas community – in reality a community of communities – the label of a crisis by their country’s leader ahead of his visit is a confusing one, insofar as the issue of illegal immigration has personally affected them.

“There’s no doubt people are coming,” Guerra said, standing in the shadow of the letters he used to spell out the marquee message that Trump could catch a glimpse of on Thursday. “But we have to be mindful. People have always been coming."