BROOKS COUNTY, Texas — The pain of missing a brother, a son, is quite possibly as difficult as looking for him among the dead.

Brooks County Sheriff Benny Martinez keeps years of binders with information on human remains found in his county. They are presumed migrants who were making their way into the U.S.

“Every person that dies belongs to someone,” Sheriff Martinez said.

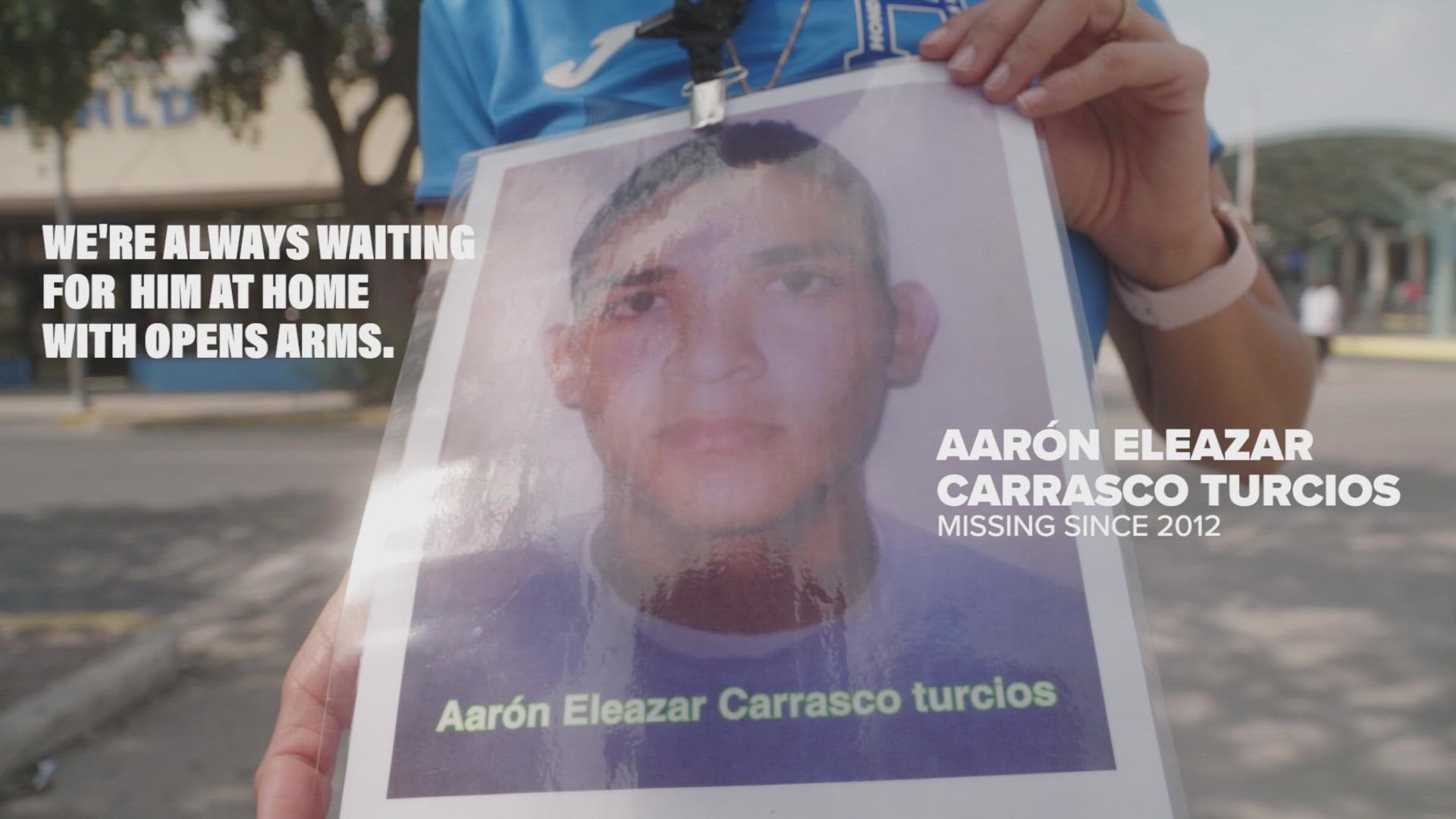

Keren Carrasco’s brother Aaron Eleazar Carrasco Turcios, from Honduras, has been missing for nearly 10 years.

“He wanted to come to the United States, but I don’t know if he was able to achieve it,” Carrasco told KENS 5. “One day he will return. We’re always waiting with him with open arms at home. With lots of love.”

Carrasco is traveling with three mothers looking for their sons. The women had to look through Sheriff Martinez’s many books labeled “Human Remains,” trying to see if their loved ones were in them.

“I looked for him in there, even though I didn’t want to,” Carrasco said.

“Three mothers looking for their sons and it’s been more than five years,” Sheriff Martinez said. “That’s a long time. I can see in them the desperation to find them [their sons].”

Time hasn’t stolen hope that they’ll someday find their loved ones alive.

“I was very happy that I didn’t find my brother in there because we want to find him alive,” Carrasco told KENS 5, after looking through the books of human remains. “That’s what we’re waiting for.”

Part of the search is submitting DNA, which the women did at the Brooks County Sheriff’s Office.

“What if they did cross at a different location besides here and another county has them?” Sheriff Martinez said. “If everyone processes like we do, we should be able to make a connection.”

“It’s one of those things that is going to take a while. This is long term,” the Sheriff added.

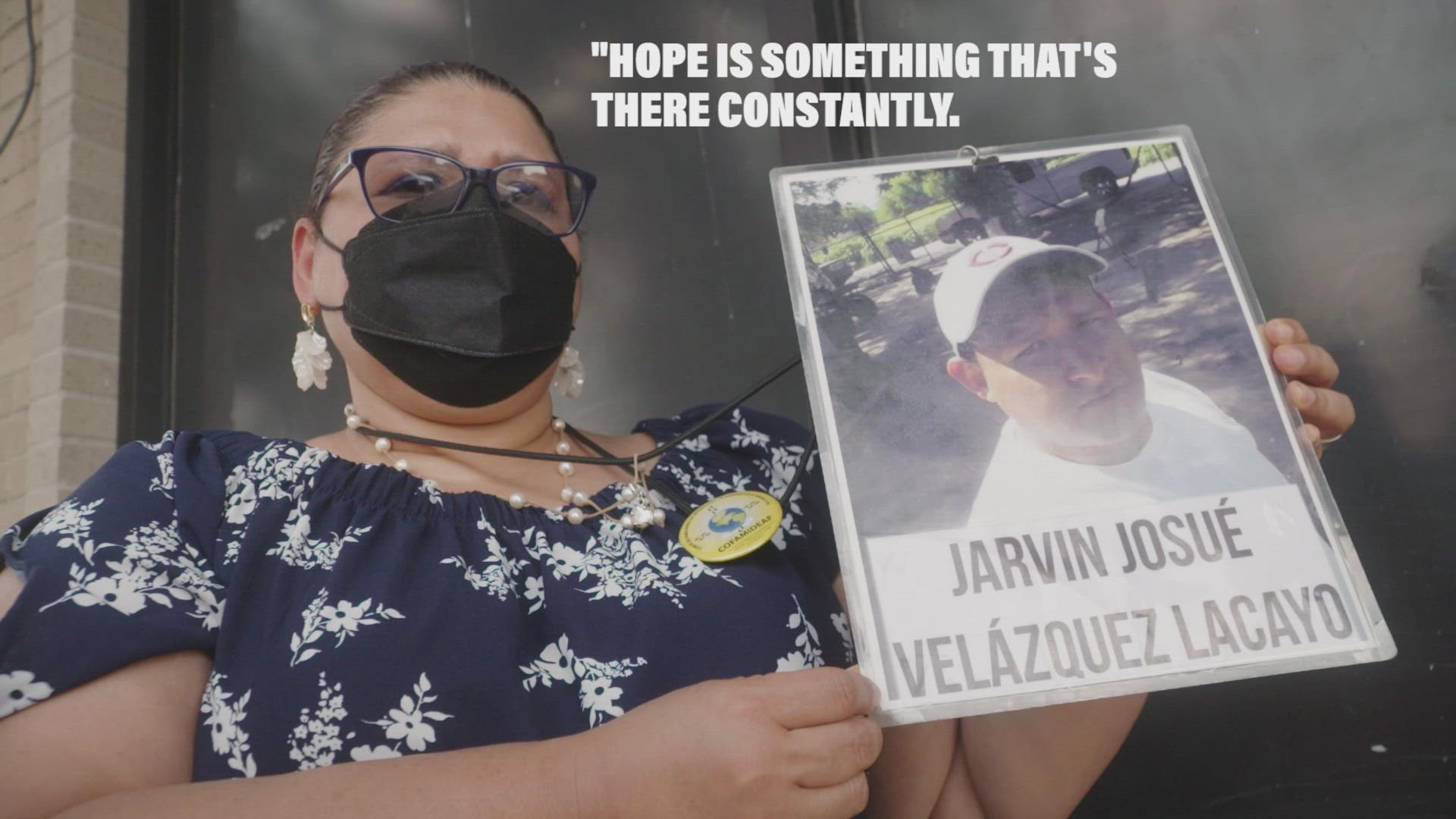

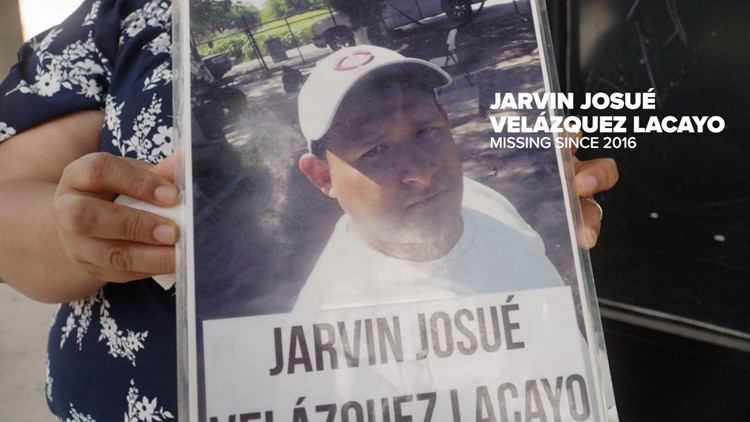

“I’m looking for my son alive,” said Angela Lacayo, who’s been looking for her son since 2016.

She said he left Honduras to provide for his children, because he couldn’t find a job.

“My hope tells me my son is alive. Hope is something that's there constantly. As a mother, you do the impossible to get answers about our sons,” she said.

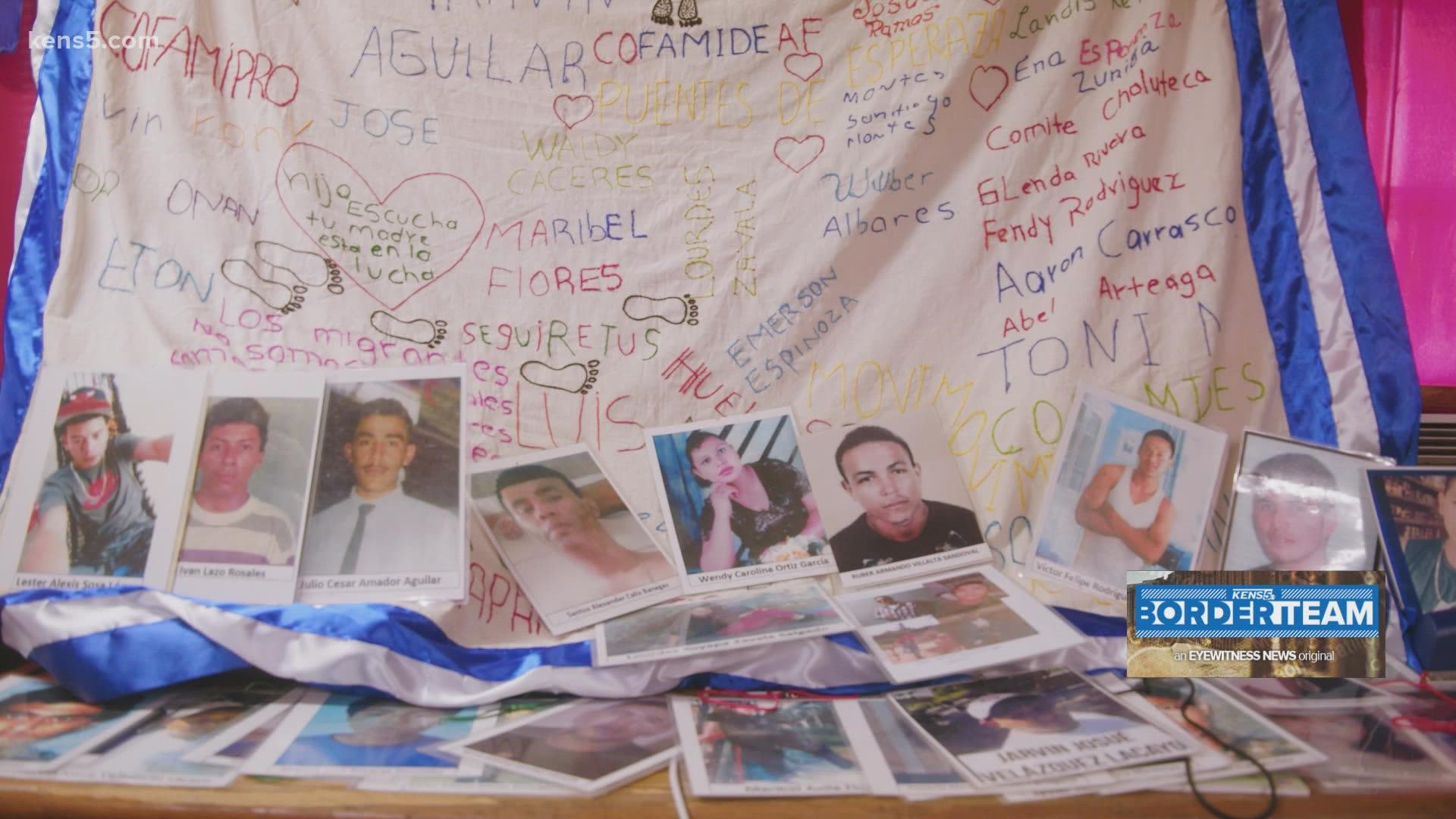

The four women told KENS 5 they’re in the U.S. representing many other moms and sisters who couldn’t make the journey, couldn’t get the precious visa to be able to look for their sons in the United States.

“It's very difficult. Not all the mothers and fathers have the necessary conditions to get a visa,” Lacayo said. “We need to keep looking for opportunities in the consulates, so they can issue humanitarian visas or temporary visas to come, make the searches [possible], We have representation of one mother per country, because [in] the embassies now with the pandemic, the process is slower.”

“Everything needs to change,” said Sheriff Martinez. “Definitely [need] a good strong bipartisan reform on this issue, immigration reform.Instead of them coming across the river, come across correctly—through the port of entry, with some type of ID, with some type of card identifying you,” Sheriff Martinez said. “Right now, no one seems to make an effort to even get to the table, even get to the middle and put something together.”

When Central Americans go missing on their way to the US, their mothers go searching

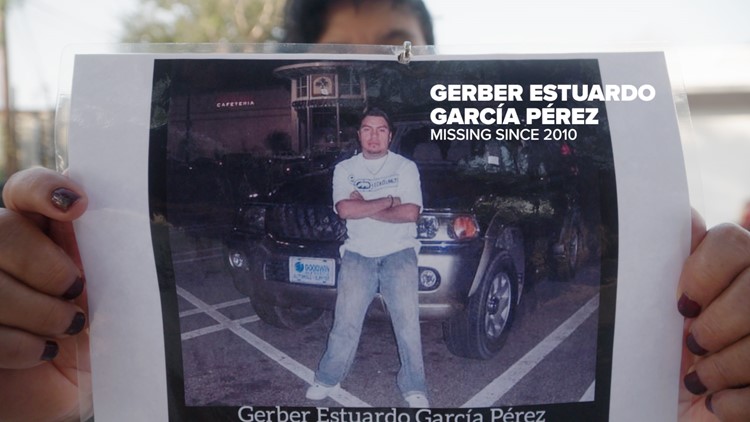

Irma Yolanda Perez is from Guatemala City. She traveled with Lacayo to look for her son, Gerber Estuardo Garcia Perez. She said he’s been missing since 2010.

“That was my son’s objective: to migrate, to be able to support his brother, me and his son,” Perez said.

“A lot of people call it the American dream, but the truth is that a lot of them migrate because of extortion in Guatemala,” she added. “My husband was murdered because of extortion. We’ve been persecuted, we’ve had to move from place to place. I ask God to be able to see him before I close my eyes.”

Mothers can only do so much. Strangers like Kate Spradley, professor of anthropology at Texas State University, have long stepped in to help.

“We're in San Ygnacio, at a local cemetery conducting examinations of unidentified remains that are presumed migrants,” Spradley described to KENS 5. “Our goal is to locate them in the cemetery, exhume them, and take them back to the lab to try to figure out who they are and send them back to their families.”

Doctor Spradley and her students have been looking for and helping to identify remains for many years. On this particular early morning, they were digging and sifting through earth in Zapata County.

“We have about 250 unidentified individuals in our lab right now,” Spradley said. “We've identified about 50 so far.”

It’s a long, difficult process, aided not by burial records but someone’s memories that a person was put in the ground, here, somewhere.

“We don't know how many remains we expect to recover here [in Zapata County] because there are no written records,” Spradley said. “The cemetery workers, the maintenance workers told us they remembered a few in one corner. A funeral director told us he remembered one in another corner. So, we found four so far, we could find a few more. We could find no more.”

Spradley says she’s been doing this work since 2013, and conducting exhumations since 2017. The longer she does it, she says, the more she believes they’re only scratching the surface.

Spradley believes this work could take decades.

“We were in Brooks County and there was a woman who came up to us and said, ‘I can't buy the plot next to my father because unidentified individuals are buried there.’ We dug a trench and we found 12 people buried in the area that this one community member told about,” she said. “And among those 12 individuals was a man from Honduras who had been missing for 21 years. Through DNA working with the Argentine forensic anthropology team, we were able to identify him and return him to his family after 21 years.”

“I, along with the rest of my team, feel that these individuals deserve the right to be identified,” Spradley added. “And the families deserve the right to know what happened to their loved one, and to have those remains back. So, we do it. We do it for the families.”

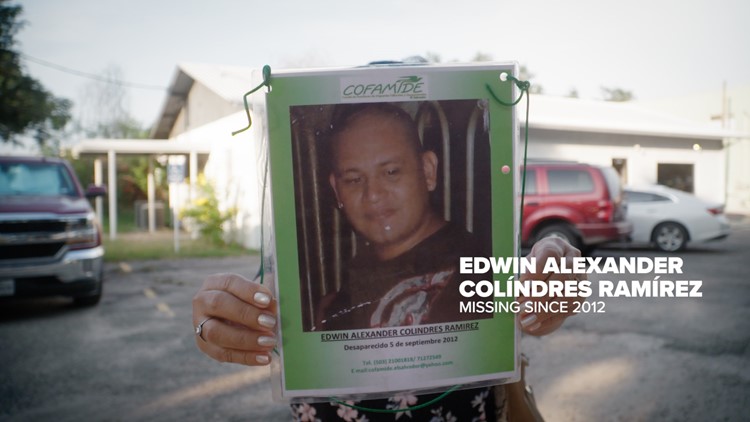

Maria Aracely Ramirez De Mejia traveled to the U.S. from El Salvador, looking for her son who disappeared in 2012.

De Mejia told KENS 5 she last spoke to Edwin Alexander Colindres Ramirez when he was in McAllen.

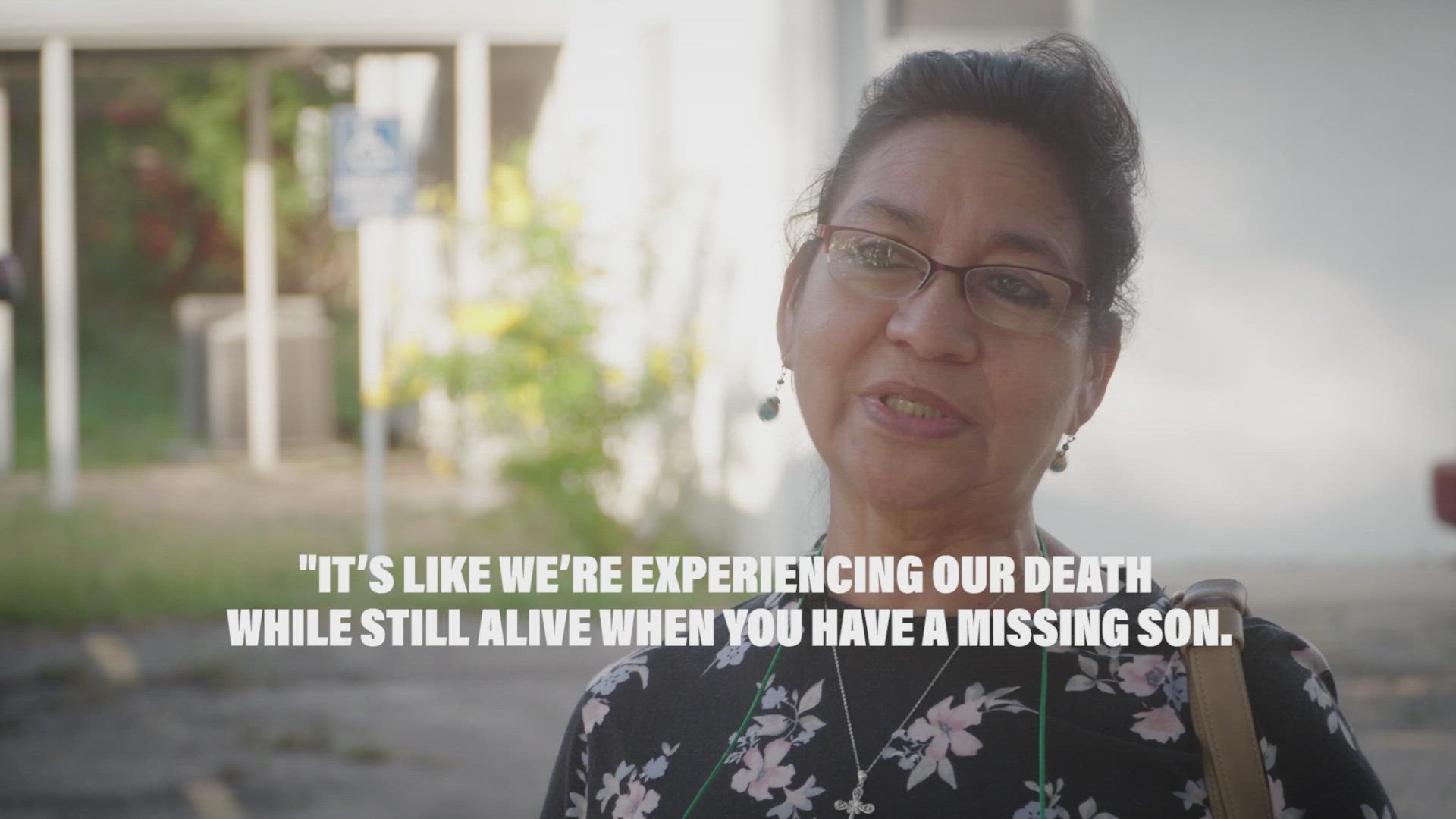

“It’s like we’re experiencing our death while still alive when you have a missing son,” she said. “If he is somewhere watching this report [I want him] to communicate with us, for him to know that I love him, that I’m looking for him. He’s in my heart and that one day we’ll meet again.”

While in the U.S., the moms and a sister planned to travel to several other cities and meet with members of Congress.