EAGLE PASS, Texas — “This is as close to being a cowboy, but with bankers’ hours.”

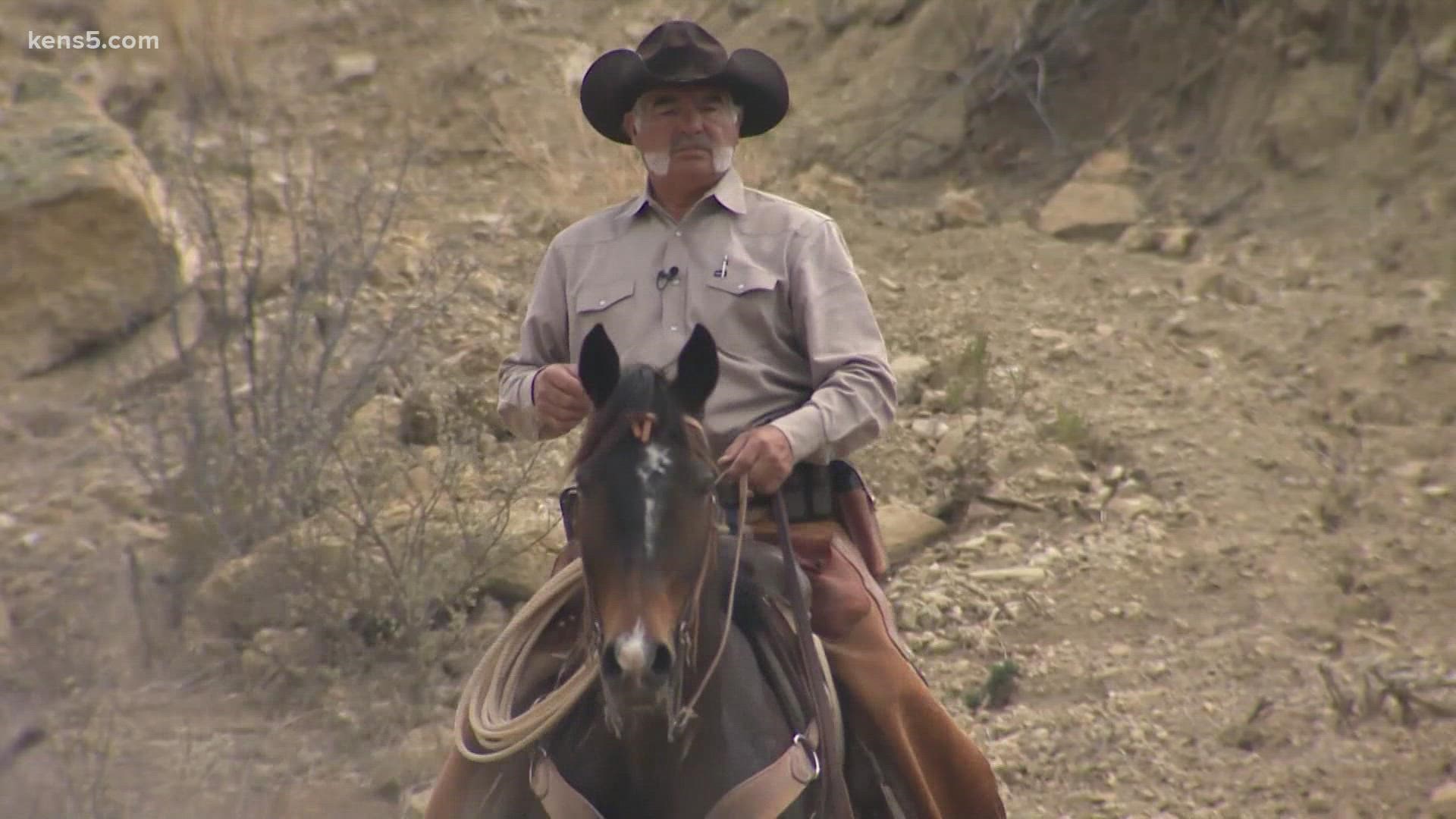

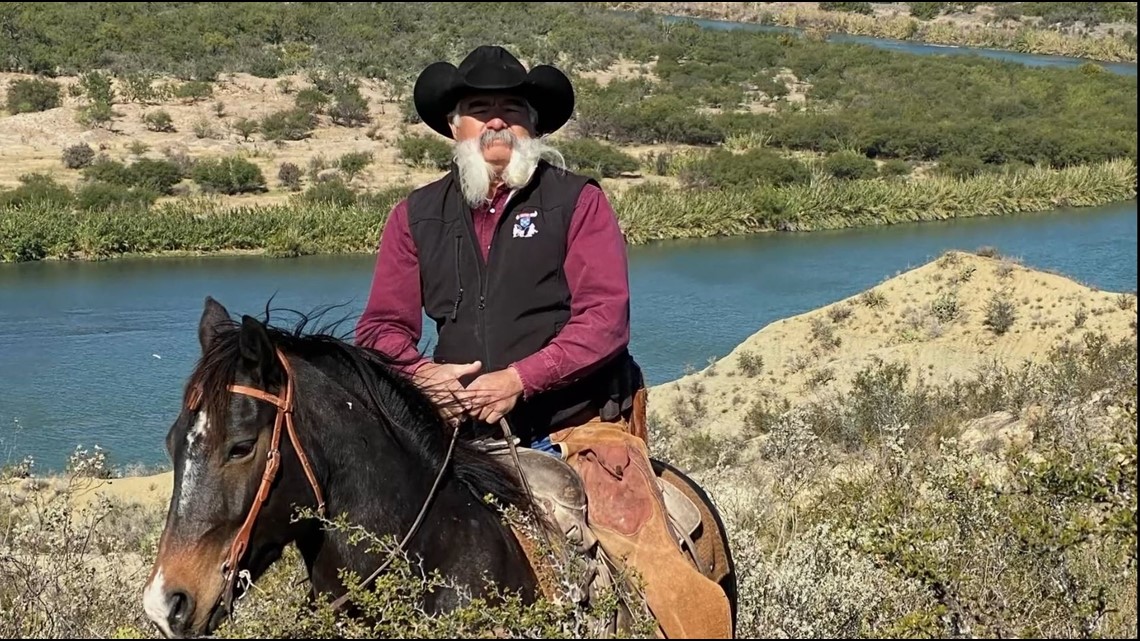

So says an older cowboy as he finishes saddling up his horse, Smoky, to ride along the Rio Grande in the Eagle Pass area, right by the Texas-Mexico border.

“Usually, it’s just him and I. Monday through Friday."

A cowboy version of bankers’ hours comes with fewer comforts, like having to wear chaps while riding in order to protect legs from thorns and stabby twigs that fill the vast, beautiful landscape near the river.

As much as the landscape is unforgiving and the job physically challenging, it’s also freeing.

“You’re kind of your own boss,” this older cowboy tells me.

His name is Tony Romo. No, not that Tony Romo, formerly of the Dallas Cowboys. This Tony Romo isn’t known for throwing a football… or his work along the Rio Grande for 45 years, for that matter

“Most people (say), ‘You know, Tony Romo, the guy with the mustache?’ Yes, I'm known for sporting a decent mustache,” Romo told me.

“He grows it pretty special, yeah,” added Romo’s younger brother, David.

Instead of scoring touchdowns, this Romo measures his success in the prevention of invasive pests.

He and his brother are tick riders for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Tick riders are also known as the mounted patrol inspectors, or river riders.

The job has been around since 1906. It only exists in Texas, and only along the Rio Grande from Del Rio to Brownsville in what is known as a permanent quarantine zone.

“This program is extremely important for the cattle industry here in the U.S.,” said Teofilo Vela, Romo’s boss and formally known as field operations supervisor for Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program in Northern Counties. “We stop an invasive pest coming in and being detrimental and extremely bad for American cattle.”

Vela said there’s only about 70 mounted patrol inspectors like Romo in the program.

The tick riders patrol alone. The ones KENS 5 followed on one day in May worked the Eagle Pass area, along the Rio Grande and the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico.

“You’re looking for signs of activity that don’t belong,” said Romo. “You start tracking those tracks to see where they’re going.”

Romo and Vela tell KENS 5 the riders are looking for livestock—cattle and horses that strayed from the Mexico side of the Rio Grande to the U.S. The livestock could be carrying cattle fever ticks.

“The river itself is not a boundary,” Vela said. “To them, they don’t know if they’re in one country or another.”

Vela said the livestock on the Mexico side of the river is immune to the disease the ticks carry. But the livestock on this side of the river aren’t, and there’s no vaccine. So the only way to control the Texas Cattle Fever is to prevent contact with the ticks, check and treat the cattle that wanders across or local animals that have been exposed.

“It's either gonna get sick or it's gonna die,” Vela said about livestock on the U.S. side of the river. “It's very costly, very costly to the industry.”

The cattle that wanders into the country is checked, treated and can be returned to its owner. If not, it’s liquidated.

Since the riders work by themselves, the job might seem lonely.

But Romo sees himself as a part of something bigger. So he’s never alone.

“I have my friend,” he said, pointing to Smoky.

“He’s always with you,” Romo said, pointing to the sky. “If you care to take him with you.”

Romo’s been out here for 45 years. He grew into the job, after watching his dad do the work. He’s the oldest of six. His baby brother David is a tick rider as well.

“I did grow up with it, and watching him (Tony), yes, I can say he’s a big part of it,” David said. “When you love your job, that's not work, you know.”