SAN ANTONIO — The photo of a daughter clinging onto her father as their lifeless bodies float in the Rio Grande captured the nation this week while casting a light on the crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The father was traveling from El Salvador with his wife and toddler when he and his daughter were swept away by the river's current.

Incidents like this are not rare.

Since the beginning of this year, the Webb County Medical Examiner has recovered 74 bodies. County Medical Examiner Dr. Corinne Stern said she’s at capacity following an increase of deaths in her area, adding it's a challenge at time seeking out the loved ones of migrants found dead.

Thousands are gambling their lives annually on the southern border desert or the Rio Grande in search of a better life.

“Unfortunately, far too often, we do find people that have drowned,” said Felix Chavez, chief Border Patrol agent in the Laredo Sector.

The bodies are usually found on private proprieties or federal land.

“We see a large number of border crossing deaths,” Stern said.

In less than a week this month, Webb County recovered 11 migrant bodies. “It takes up about 40% of our practice here,” Stern said. She said over the years she has seen an increase in woman and children found dead crossing the border.

“These are Jane Does and John Does and Child Does," Stern said. "They could be one of 7.5 billion people and we don’t know who they are."

It’s why she examines every shred of evidence and takes photographs.

“We are looking for scars, marks, tattoos,” she said. “We do full dental charts and we have a full X-ray system, so we can do full dental radiographs as well.”

She said she will often find names written on the bottom of a shoe or inside a belt, but says phone numbers and cell phones are the most reliable piece of evidence.

Stern calls the phone numbers found, often the starting point to piecing together an identity. “We start asking them where they are from, and then we start asking them (about) scars, marks, tattoos,” she said.

If the family can prove, with fingerprints and documents, it’s their relative, they become part of a lucky group.

“They are eventually going to make it back home,” Stern said.

She acknowledged it can be an expensive and time-consuming process for families to recover the bodies of their loved ones. If Stern can’t find a lead, she enters the migrant into a database compiled of missing people reported to the medical examiner, Border Patrol or consulates in hopes of a match.

Cecilia Garcia Pena with the Mexican Consulate said they receive about five phone calls a day from people desperately searching for their relatives. She said while some families may know their family member is already dead, others have no idea.

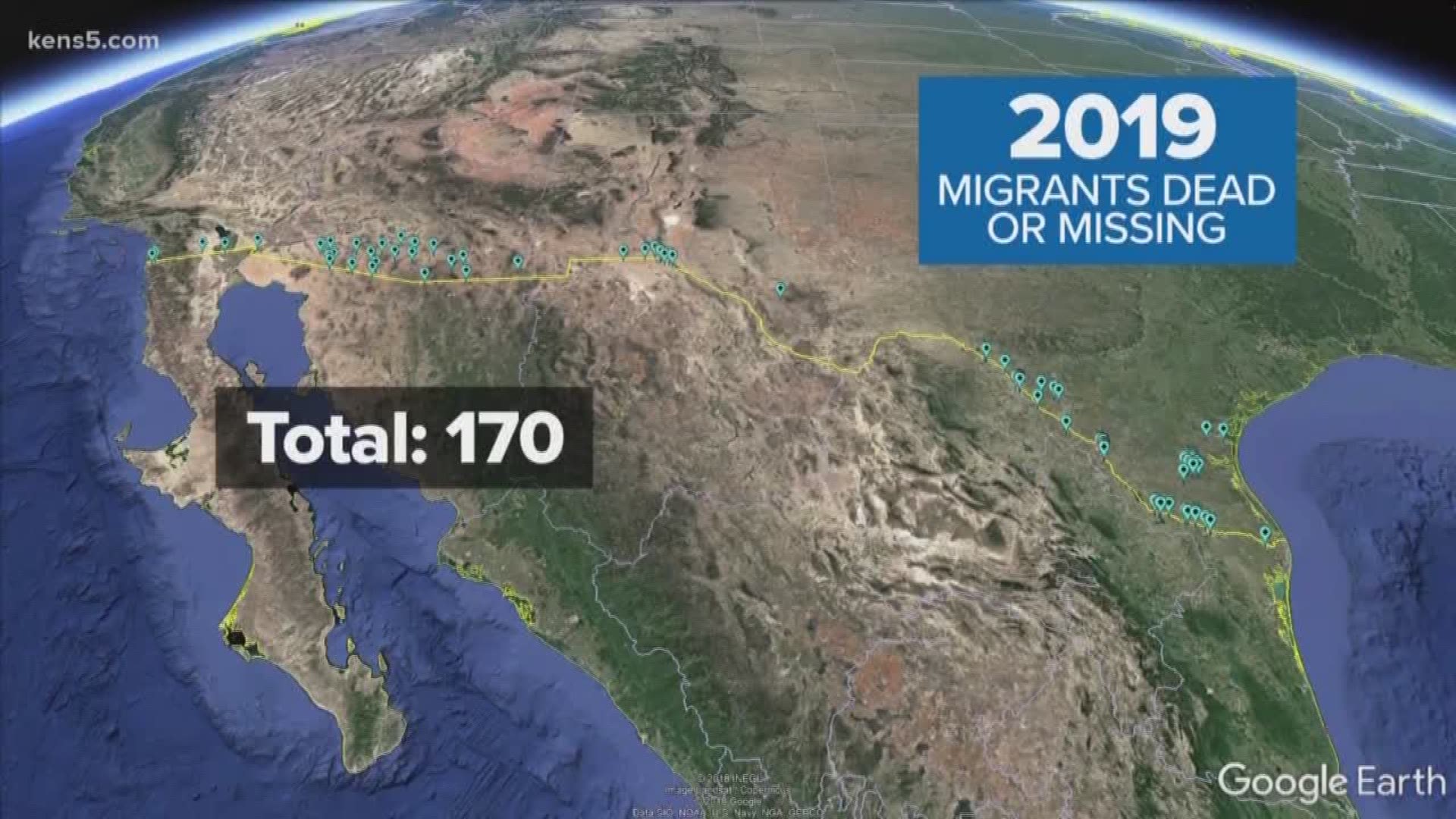

According to the Missing Migrant Project, about 170 people have died or gone missing along the U.S. Mexico border so far in 2019.

The biggest causes of death:

- 41 from drownings

- 15 in vehicle accidents

- 53 are unknown remains

Stern said bone DNA samples can be submitted to labs, which will upload the results on the combined DNA Index System. It can take up to eight months to find out if he person has a record or if a family member is searching for them.

Meanwhile, migrants who can’t be traced after exhausting a DNA test will be buried in the county where they were found, their identity remaining ambiguous.

It’s where they become just another number, nameless, tucked away in a cemetery far from home.

Tracking down a family member can be an expensive process for families in other countries. It’s why the consulate said there are programs available to help families cover a percentage of the expense to bring their loved ones home.

POPULAR ON KENS5.COM: