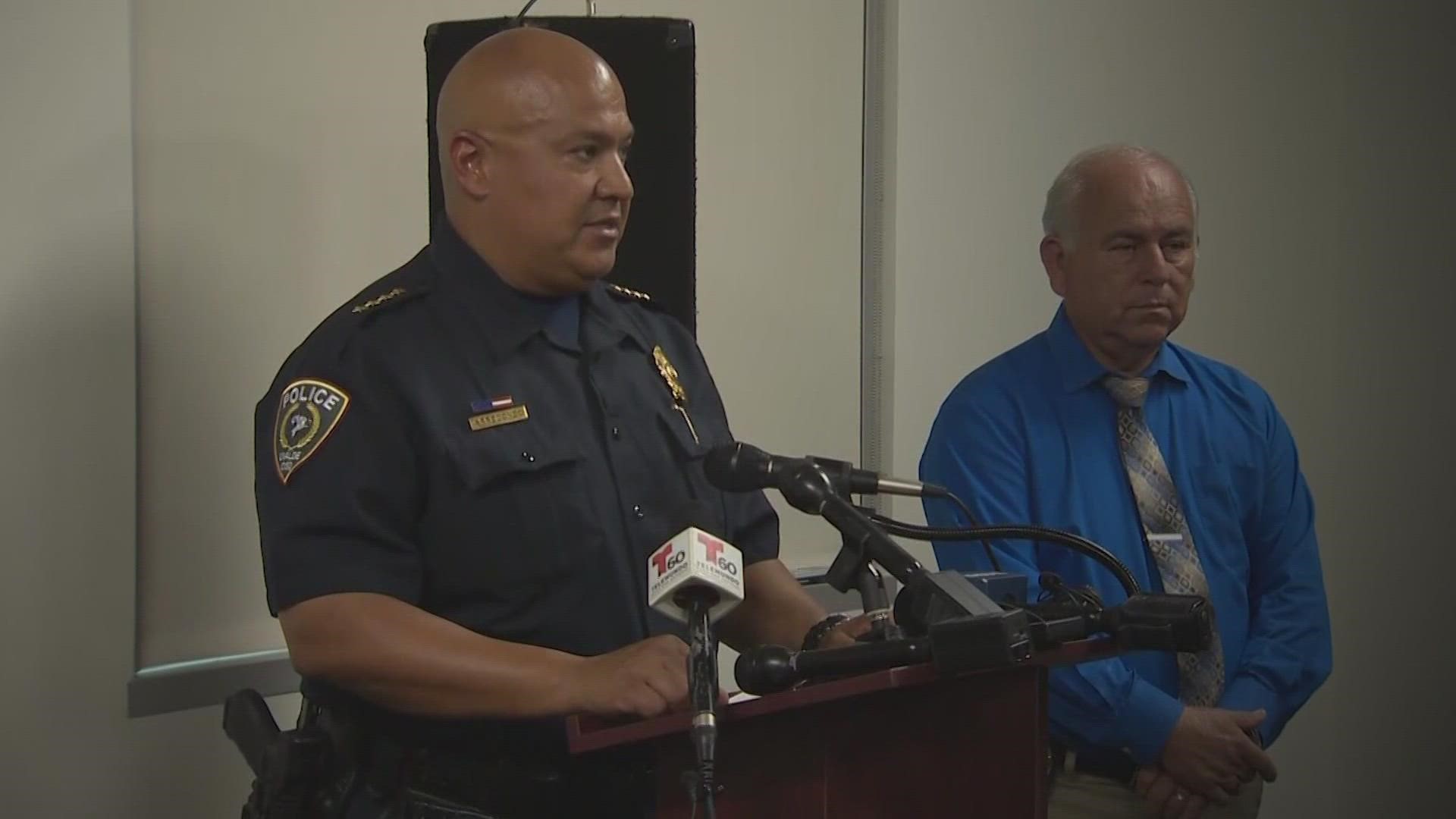

UVALDE, Texas — In the weeks since officers in Uvalde waited more than an hour to confront a gunman who killed 19 children and two adults at an elementary school, police departments across the state have asked themselves a crucial question: If they faced a similar situation, would they be able to quickly stop the gunman?

The images of parents and students pleading with officers to take action at Robb Elementary School on May 24 before a tactical team of federal agents finally breached a classroom and fatally shot the 18-year-old gunman deeply disturbed Marfa police Chief Estevan Marquez.

“I keep telling my officers, ‘I don't want to ever have to go through that,’” Marquez said. “‘I don't want you guys to ever just be standing around when innocent children are being shot in the school, in the classroom.”

Police departments across Texas now find themselves trying to reassure communities that their officers are prepared to handle mass shooters — and reminding officers of their training. Since the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado left 12 students and a teacher dead, active-shooter training instructs officers to immediately confront shooters, even if an officer is alone at the scene.

Active-shooter training is a part of the state’s core curriculum for officers when they receive basic training. The state also requires police officers stationed at schools to receive active-shooter training — a mandate that’s been in place only since 2019. But there’s no agreed-upon standard or state requirement for how regularly an officer should train for an active shooter.

Police officials and law enforcement experts also admit a stark reality: No matter how much training they have, there’s no guarantee that officers will follow their training and confront a shooter at the crucial moment.

Donna police Chief Gilbert Guerrero, who oversees a force of 30 patrol officers in a border town of some 16,000 people, said he told his officers that they should consider changing jobs if they were “not willing to make that sacrifice” by facing down a gunman and risking their lives.

Uvalde’s school police had trained repeatedly for a mass shooting, including a drill in March at Uvalde High School. Guerrero said he hopes his officers would remember their training in the moment — but he’s not sure they would.

“It’s up to the individual officer’s courage and the state of mind if they can do it,” Guerrero said.

This week, Gov. Greg Abbott directed the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training program at Texas State University in San Marcos — a program considered the nationwide gold standard for active shooter training — to put Texas school district police officers at the front of the line for additional training — and to provide training before the start of the next school year this fall.

The program, known as ALERRT, was founded three years after the Columbine massacre. It trains officers from across the nation to deal with mass shooters and already has seen an uptick in requests for active-shooter training in the wake of the Uvalde shooting, said Pete Blair, ALERRT’s executive director.

The program trains hundreds of law enforcement officers each year but isn’t able to handle the demand in a typical year, Blair said. The program receives $2 million a year in state funding and also receives federal grants like a $9.8 million award last year from the U.S. Department of Justice.

Abbott did not say whether the program would receive additional state funds to train more school police officers. His office did not immediately return a request for comment.

The point of active-shooter training is “to increase the probability that you perform well during a crisis,” Blair said, adding that the more training an officer has, the better prepared they will be to face down a rampaging gunman.

“The hope is, even if initially it’s a shock to you and you freeze up, that you fall back on your training,” Blair said. “The best we can do is give you training to try to prepare you mentally and physically for the situation.”

At the same time, Blair said, training “doesn’t guarantee” that officers will perform well when they’re under fire.

“Only so much time and money”

After the Uvalde shooting, police departments told The Texas Tribune they plan to do more active-shooter training. For example, the Dallas Police Department said in a statement that additional training “will take place not only in our schools, but also critical infrastructure like malls, places of worship, and movie theaters.”

In the absence of any state requirement for how often Texas officers get active-shooter training, ALERRT is considering recommending that they train every two years, Blair said.

Although ALERRT offers free active-shooter training to officers from anywhere in the country, many smaller departments don’t have the resources to continually train for active shooters the way big urban departments can, said Jimmy Perdue, head of the Texas Police Chiefs Association.

Departments have to find officers to cover shifts for those in training and pay for costs like travel, lodging and meals if training doesn’t take place nearby — which can be more difficult for smaller departments with fewer officers and slimmer budgets, Perdue said.

“It doesn’t make them any less professional, it doesn’t make them any less prepared,” Perdue said. “It just means that they don’t have the ability to maybe do it to the levels that are the expectation that we have in the major urban centers.”

Marfa’s police department — reestablished in 2017 with four patrol officers for a town of fewer than 2,000 people — hosted an ALERRT training session for neighboring law enforcement agencies in March at Marfa High School. Before that, Marfa officers hadn’t received formal ALERRT training since 2018, according to records from the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement — which Marquez blames in part on the pandemic.

The department otherwise drills for active shooters twice a year, Marquez said, and it’s possible it could add a third training session.

In the meantime, the department is looking for ways to shore up its stock of tactical equipment, Marquez said. Marfa police have bullet-proof vests and rifle-resistant armor the force received through grants that would be helpful when encountering a shooter, Marquez said, but the agency still needs equipment like helmets and shields and may need to make cuts elsewhere in its budget to afford them.

Another thing that worries Marquez in the event of a mass shooting: Marfa has one ambulance, and the nearest hospital is 30 minutes away in Alpine.

Police departments have to balance mass-shooter preparation with other demands, experts said. They also must train in areas like de-escalation tactics and spotting human traffickers while maintaining enough staffing to do their regular patrol work. Although mass shootings are more common in the United States than in other parts of the world, they’re still fairly rare and account for a small percentage of crimes that involve firearms.

“There’s only so much time and money that it makes sense for an individual agency to invest in something,” said Phillip Lyons, dean of Sam Houston State University’s College of Criminal Justice. “This is a very high-consequence event, but has an extremely low probability of happening to the vast majority of agencies out there. So with precious limited resources, what do we invest them in?”

Disclosure: Texas State University and Sam Houston State University have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This story was originally published by The Texas Tribune.