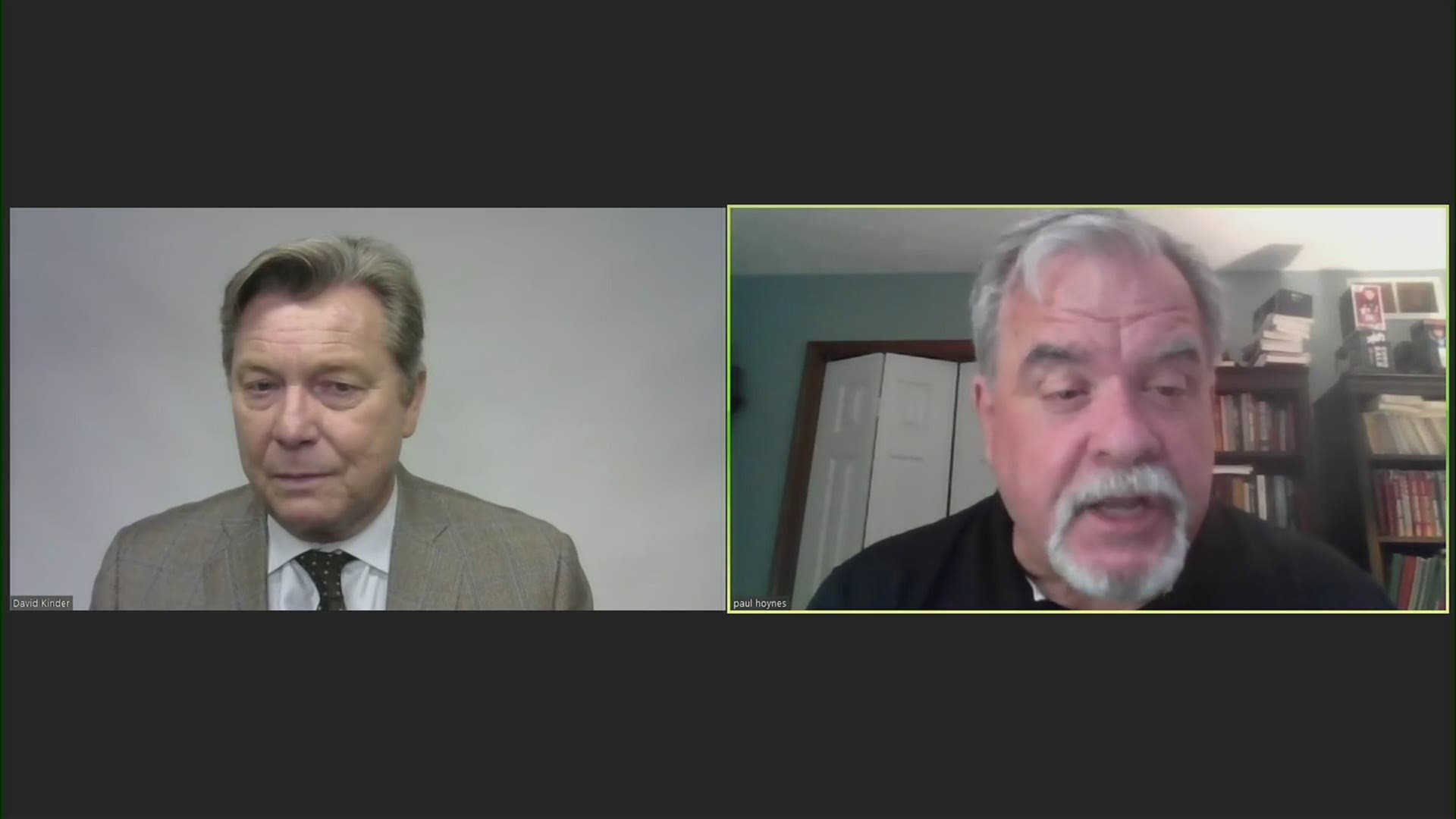

CLEVELAND — In a move most thought the club would never make, the Cleveland Indians have decided to get rid of the name they have held for the last 105 years.

It's a step that has polarized commentators and fans, with many remembering their fond memories of the Tribe over the preceding decades while also wondering if the moniker is offensive to Native Americans and therefore inappropriate to continue.

After months of suggestions for possible new identities came flowing in (Buckeyes, Spiders, Rockers, etc.), the team announced on July 23 that it will become the Guardians after this season.

Unless they move to a different city, major league sports teams rarely change to their names, and the process in the era of social media can often be rife with twists and turns of vocal opinions. However, it does beg the question: How did Cleveland's MLB franchise adopt the nickname "Indians" more than a century ago?

Chances are, you think you know the full story: On the suggestion of fans, the club chose the name in honor of Louis Francis Sockalexis, a Cleveland professional ballplayer who was one of the first Native Americans in the game's history. The team's official media guide carried this claim as recently as this decade, and a plaque honoring Sockalexis even resides at Progressive Field's Heritage Park.

While there is some truth to this, the actual story is far from simple, with a lot of moving parts that eventually led to where we are today.

Who was Louis Sockalexis?

The son of a Penobscot Indian chief, Sockalexis was born on his tribe's Maine reservation in 1871. He was a gifted athlete and wound up playing baseball as well as football and track at Massachusetts' College of the Holy Cross. After two seasons and a .444 batting average, he transferred to the University of Notre Dame, but it was there that his off-field demons truly began to creep up on him.

Not long after arriving in South Bend, Sockalexis was expelled from school due to continued problems with alcohol. Longtime Cleveland sportswriter Terry Pluto detailed what was apparently the final straw in his 1998 book "Our Tribe":

"Sockalexis and one of his buddies busted up a South Bend watering hole called Pop Corn Jenie. They were drinking Old Oscar McGroggins, which apparently was strong enough to remove two coats of paint from a boiler. It also got Sockalexis' blood boiling as he began to break chairs over his knee, throwing sticks of wood out the window. He was carted off to the pokey, where the South Bend Tribune found out that Notre Dame's star player was behind bars for assaulting policemen and other indiscretions."

Sockalexis' college career was over, but in a surprise twist, baseball would be what got him out of jail: According to Pluto, Sockalexis' friend Doc Powers had connections with the Cleveland Spiders of the National League, and told the team of the now-inmate's potential on the diamond. The Spiders brass then bailed Sockalexis out, and signed him for $1,500 (more than $46,000 today).

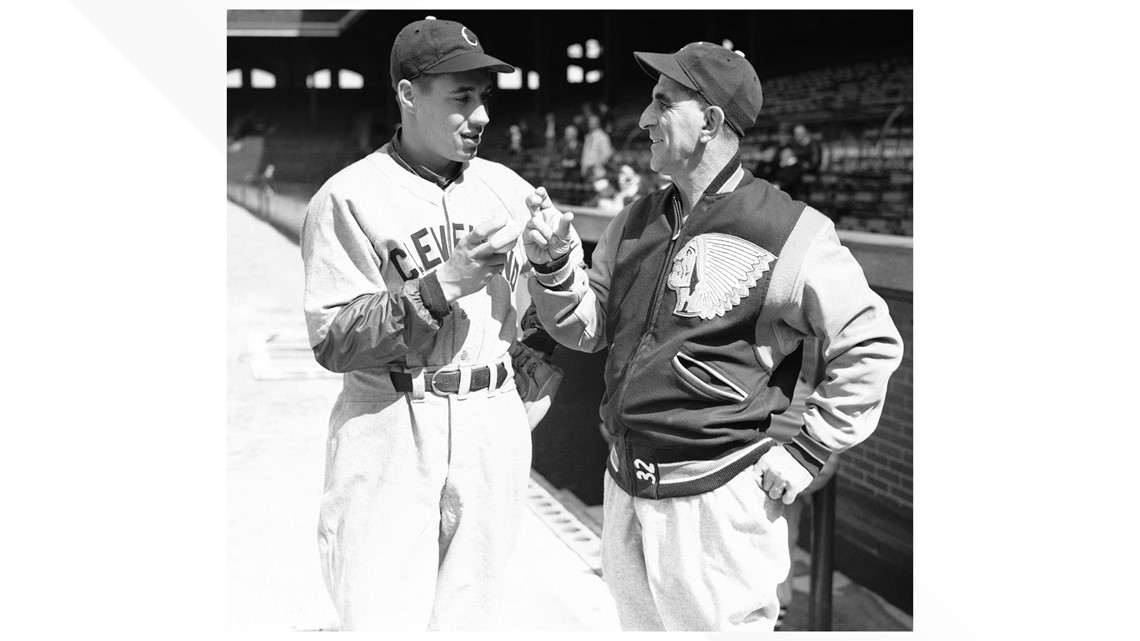

Sockalexis made his professional debut in April of that year, with Northeast Ohioans buzzing about the Native American ballplayer they had heard so much about. He quickly wowed with his powerful bat and rocket throwing arm (it was once said he threw a base runner out from 414 feet away on the fly) and soon gained national recognition, with the publication Sporting Life even declaring of the team, "THEY'RE INDIANS NOW."

"There is no feature of the signing of Sockalexis more gratifying than the fact that his presence on the team will result in relegating to obscurity the title of 'Spiders' by which the team has been handicapped for several reasons, to give place to the more significant name 'Indians,'" the report read, indicating fans' disgust with the club's "official" nickname.

Sadly, the glow around Sockalexis would soon fade and his drinking again played a role: On July 4 of that first season, Pluto writes that the 25-year-old was drunk while running along a second-story hallway of a bar-brothel. Whether he did so purposefully or by accident remains unclear, but he ended up going through a window and badly injuring his ankle. Sockalexis would play just eight more games that season.

Even in glory, Sockalexis had already dealt with racism at the ballpark, with insensitive fans yelling things like "Scalp 'em!" or doing rain dances in the stands. Unfortunately, the taunts got worse as his play declined, and The Plain Dealer went so far as to refer to him as "A Wooden Indian" and "a broken idol."

"[Sockalexis] acted as if [he] had disposed of too many mint juleps previous to the game," the paper stereotypically wrote following a particularly tough loss to Boston. "A lame foot is the Indian's excuse, but a Turkish bath and a good rest might be an excellent remedy."

Sockalexis would still bat .338 with 94 hits and 16 stolen bases in 66 games, but was never the same again. After averaging only .224 in 1898, he was released just seven games into the 1899 season, a year that would see the Spiders—ransacked by crooked owners—finish a still-MLB-record-worst 20-134 before folding altogether.

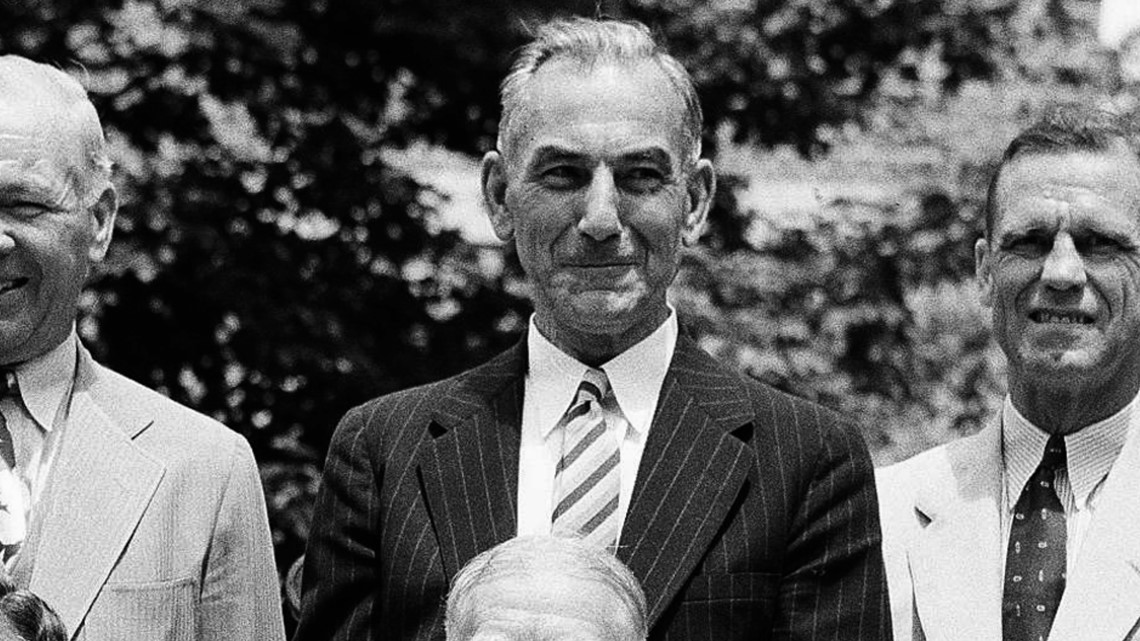

His Major League career over after 94 games, Sockalexis would find some success coaching children before his health rapidly declined. He died in 1913 at the age of just 42; for his efforts in baseball, he was later posthumously inducted into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame.

'Naps': Honoring a legend

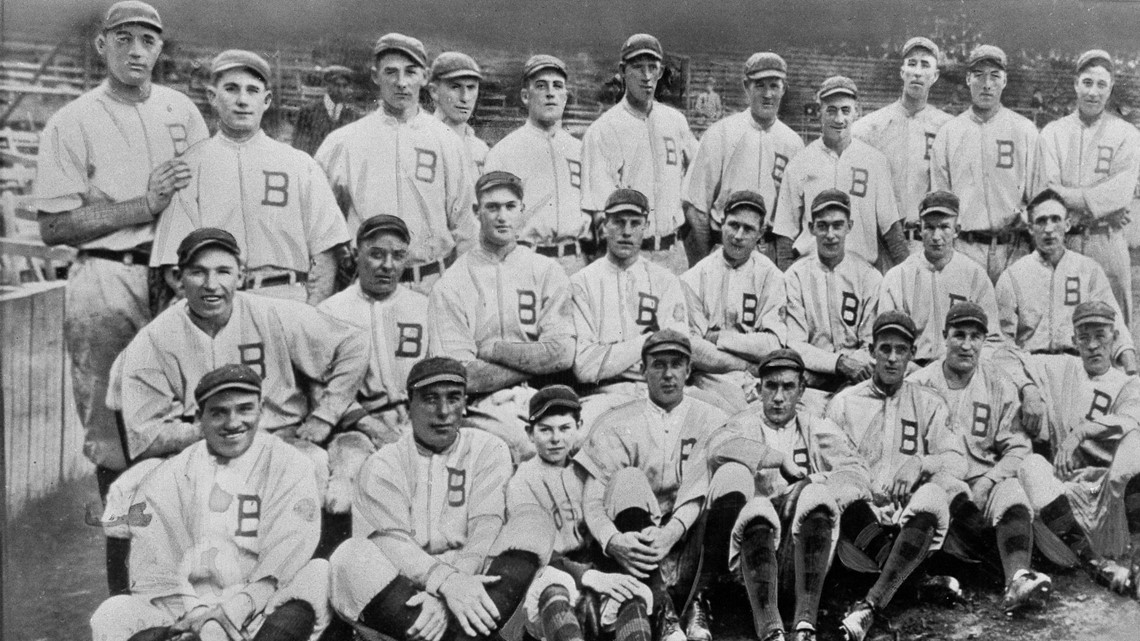

Two years after the Spiders went bust, Cleveland got itself a new team as a charter member of Ban Johnson's American League. The startup circuit would soon equal the NL for baseball supremacy, but when it came to naming the squad on the lakefront, Sockalexis' exploits had all but been forgotten.

Cleveland went by the "Blues" in 1901 in reference to the color of their uniforms, followed by a brief stint as the "Bronchos" (good luck getting away with that name in Cleveland today). However, it would be another player who finally gave the club an identity that stuck: Napoleon Lajoie.

A towering second baseman with a mighty bat, Lajoie gave the AL the credibility it needed when he shockingly jumped the NL's Philadelphia Phillies during that inaugural campaign for the city's new Athletics team. He was a star for the A's and won the league's Triple Crown with an astonishing .426 average, but the legal fallout over his leaving the Phillies continued all the way to a decision from the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. To avoid any more liability, the A's were forced to release him in April of 1902, and just over a month later, he signed with the Cleveland Bronchos.

Lajoie's legend only grew in Northeast Ohio, and prior to the 1903 season, the team again decided to change its name. In a poll conducted by the Cleveland Press, fans overwhelmingly chose "Naps" in honor of their beloved new leader (strangely, historical accounts say Lajoie actually often went by "Larry"). He more than lived up to the hype: In 13 seasons in Cleveland, Lajoie set franchise records for hits (2,047) and Wins Above Replacement (79.8) that stand to this day, while also batting .338 with 240 steals and an impressive glove at second. He even served as player-manager from 1905-09, and just missed guiding the team to the AL pennant in 1908.

"The Frenchman" finished his career with 3,243 hits and was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937, with his plaque being adorned with the "Block C" cap he wore with the team that bared his name. It was almost the perfect story, but for one minor problem: Lajoie did not finish his career in Cleveland.

Following a subpar 1914 season that saw the Naps finish dead last and Lajoie hit just .258, the 40-year-old was dealt back to the A's as a means of getting him on a contender while slashing payroll. The Cleveland club felt it could not continue to name itself after a now-opposing player, so it decided to go back to the drawing board. Owner Charles Somers once again solicited the help of the city's sportswriters, hoping to settle on a brand once and for all.

What's in a name?

Unlike the process that selected "Naps," the new moniker was to still be solicited from fan suggestions, but this time it would be the team and the writers who made the final decision. The publications received hundreds of ideas, ranging from staying with the old nickname to things like "Foresters," "Tornadoes," "Commodores," "Rangers," "Sixers," and "Harmonics." Yet, as Pluto writes, none of the papers mentioned "Indians" as a published suggestion.

This is where things get tricky, and where the signs of the times likely come into play. The 1914 season had been an historic one for baseball, as the Boston Braves had stormed back from last place and 12.5 games down to swipe the National League pennant before stunning the Philadelphia A's in the World Series. The "Miracle Braves" captured the hearts of fans in New England and around the country, and when it came to what made them so popular, many began to point (whether it was morally right or wrong) at their Native American-themed nickname.

Historians seem to agree Somers and the writers saw this as a dream brand opportunity, and it's quite possible at least some actively remembered the Sockalexis era with the Spiders. Obviously, an exact ripoff of the Braves would've been impossible, so the group went with what they saw at the next-best thing: "The Cleveland Indians."

As Pluto recounts, The Plain Dealer and The Sporting News correctly mentioned that the new moniker was one carried by the Spiders for a time, while The Cleveland News even directly mentioned the Braves in hoping Cleveland's hapless team could "show just as much reversal of form" as the unlikely champs. Yet when the announcement of the change was made, none of the papers mentioned Sockalexis until The Plain Dealer did so in a small January 1915 write up, after the fact.

Most felt the new name would be temporary, and team Vice President Barney Barnard even said he liked the name because, "They won't be able to poke fun at the Indians." Well, several subsequent shots from the press like "squaws" and "featherbrains" would unfortunately prove Barnard wrong, but as well all know, the "Indians" were here to stay.

What comes next?

From here, you know how things go: From also-rans to Hall of Famers, from cellar-dwellers to pennant winners, from decrepit stadiums to beautiful downtown ballparks, and even from caricatures to "Block C's," the nickname "Indians" has been the one constant of baseball in Cleveland for more than a century.

Now we know the franchise will become the "Cleveland Guardians" beginning in 2022.

“We are excited to usher in the next era of the deep history of baseball in Cleveland,” team owner and chairman Paul Dolan said in a statement announcing the Guardians. “Cleveland has and always will be the most important part of our identity. Therefore, we wanted a name that strongly represents the pride, resiliency and loyalty of Clevelanders. ‘Guardians’ reflects those attributes that define us while drawing on the iconic Guardians of Traffic just outside the ballpark on the Hope Memorial Bridge. It brings to life the pride Clevelanders take in our city and the way we fight together for all who choose to be part of the Cleveland baseball family. While ‘Indians’ will always be a part of our history, our new name will help unify our fans and city as we are all Cleveland Guardians.”

In the video, narrated by Tom Hanks and featuring the Black Keys, the team also released its new logos, which will maintain the Indians' red and navy blue color scheme. One logo features a new, stylized 'C', while the other features a 'G' with guardians wings. The team also has new fonts for both a block 'Cleveland' and script 'Guardians," reminiscent of the current wordmarks worn on the team's uniforms.

You can watch the Indians' announcement video below:

Information from Terry Pluto's "Our Tribe" and the Society of American Baseball Research contributed to this story.