In August 1982, Petti McClellan took her 15-month-old daughter, Chelsea, to the family doctor’s office in Kerrville where Genene Jones worked as a nurse.

Based on a timeline of the case in The Death Shift by Peter Elkind, they met Jones on just the second day the clinic was open.

Petti said she wanted the new pediatrician in town, Dr. Kathleen Holland, to give her daughter a checkup.

Listen to VILE Podcast on SoundCloud and download on iTunes. Also search "VILE" and subscribe through the Apple Podcast app.

As Petti recalls, the first time Chelsea went into the exam room under Jones' care, the baby girl suddenly seemed to have suffered a seizure.

"They took her to the hospital. She was there for five days. Nothing ever happened. They couldn't find any reason for her to arrest and stop breathing," Petti said.

Chelsea was rushed to Sid Peterson Hospital in Kerrville, about an hour outside of San Antonio, and later recovered.

"The only reason I took Chelsea there is (that) at the time, we didn't have a pediatrician. We had family practice. My doctor that took care of her was fabulous. I loved him. But we were raised that if you're a child, you go to a pediatrician. In my generation, I never went to any doctor but a pediatrician until I was 19 years old. That's the only reason I switched," Petti said.

After that first incident, Petti said her daughter was afraid of Genene Jones.

“When we were in the hospital and they made rounds, Jones always came with Holland, which was strange in itself," Petti said.

"Every time that she would walk in a room, Chelsea would lose her mind. She would just start crying and screaming. She would want me to pick her up, and I mean, this was every time she saw [Jones]. I'm like, 'OK, she sees a nurse, she doesn't know. Then there were the other nurses that worked on the floor. They came and got her all the time. They would just come in."

"You didn't see a lot of babies in the Kerrville hospital. At that time, Kerrville was mostly a town of retired people. You know, you saw mostly elderly people or middle-aged people. There weren't a lot of kids. The other nurses would come in the room and say, ‘I'll get you some coffee, or go take a nap. We're taking Chelsea to the nurses' station.'"

"Chelsea would be all over them, saying 'bye bye.' She was just starting to talk. She said those one-syllable words. They spoiled her rotten, and you know, she would sit up at the nurses' desk with them."

"I didn't put it together then, but the second time, I knew as soon as she gave her a shot, something was wrong. Something was way wrong," Petti said.

The second time Chelsea went into the Kerrville doctor’s office, Petti said her daughter wasn’t even sick. She only brought Chelsea along because her older son, Cameron, was sick.

“The day that Chelsea went in, she didn't even have an appointment to be seen. My son, Cameron, did. Cameron had the flu. He was sick. They said, 'We're going to go ahead and give Chelsea her immunizations because she's behind.' Jones said, 'I'll go ahead and take her.' They had a sick room [where Cameron was] because he had fever."

Petti said she ended up leaving Cameron for what she thought would only be a few minutes while Chelsea received her shots.

"I think the receptionist said she would come in and sit with Cameron. I thank God every day that Cameron did not go in that room with me."

"I've just always felt that was something that came from upstairs, because I would have never left Cameron by himself either. When I think about the fact that he could have been in that room when Chelsea started crashing... I don't know, I'm just thankful that it didn't happen," Petti said.

She went into the exam room with Chelsea, where Genene Jones was waiting.

"She already had the syringes ready. They were on the cabinet. As soon as she gave her that first shot, [Chelsea] started having trouble. I was holding her. She was across my lap, because when they're a baby, they give them their immunizations in their thighs. That's where they have the most fat and muscle."

"Immediately, she started having trouble. Something's wrong. Chelsea was looking at me, and she was crying. She was trying to say my name. Jones said, 'She's just mad because I gave her a shot.' I was like 'No, she's not mad. Something is wrong.' As I was saying that, [Jones] gave [Chelsea] another [injection], and she arrested."

"There is nobody in my life I have ever disliked enough that I would wish losing a child on. The only people that understand that is if they lose one. I wish nobody would ever have to go through that. It's a living hell, no matter how it happens," Petti said.

Test results later would show that Chelsea did not get a booster shot. Jones had injected Chelsea with succinylcholine, a powerful muscle relaxant.

“She had an IV going, but once succinylcholine wears off, it's gone. It's like you never had it, but you go through that trauma because it's not even a fast death. It's a paralytic. It just slowly shuts down every organ in your body, but the whole time it's going on, you're awake. You can hear. You can see. You can't let anybody know what's happening to you. So it's not like it's even a slow death. It's a torturous death," Petti said.

In The Death Shift, Elkind writes that Holland made the decision to transfer Chelsea to a hospital in San Antonio to help figure out what was going on with her medical care and determine the cause of what appeared to be a seizure.

Chelsea was headed there in an ambulance when she started crashing.

Petti said Genene Jones was in the ambulance, too. They ended up having to pull over in the town of Comfort, about a quarter of the way to San Antonio, without much hope of saving Chelsea.

“Somehow, [Jones] ended up getting to the ambulance, which we weren't even aware of, until the ambulance started pulling over to the side of the road between Kerrville and San Antonio. That's when we realized Holland was behind us. She jumped out of the car and Jones jumped out of the back of the ambulance."

"We're like, 'What the hell,' and they just said, 'She's crashing, she's crashing.' Jones knew she couldn't get to San Antonio," Petti said.

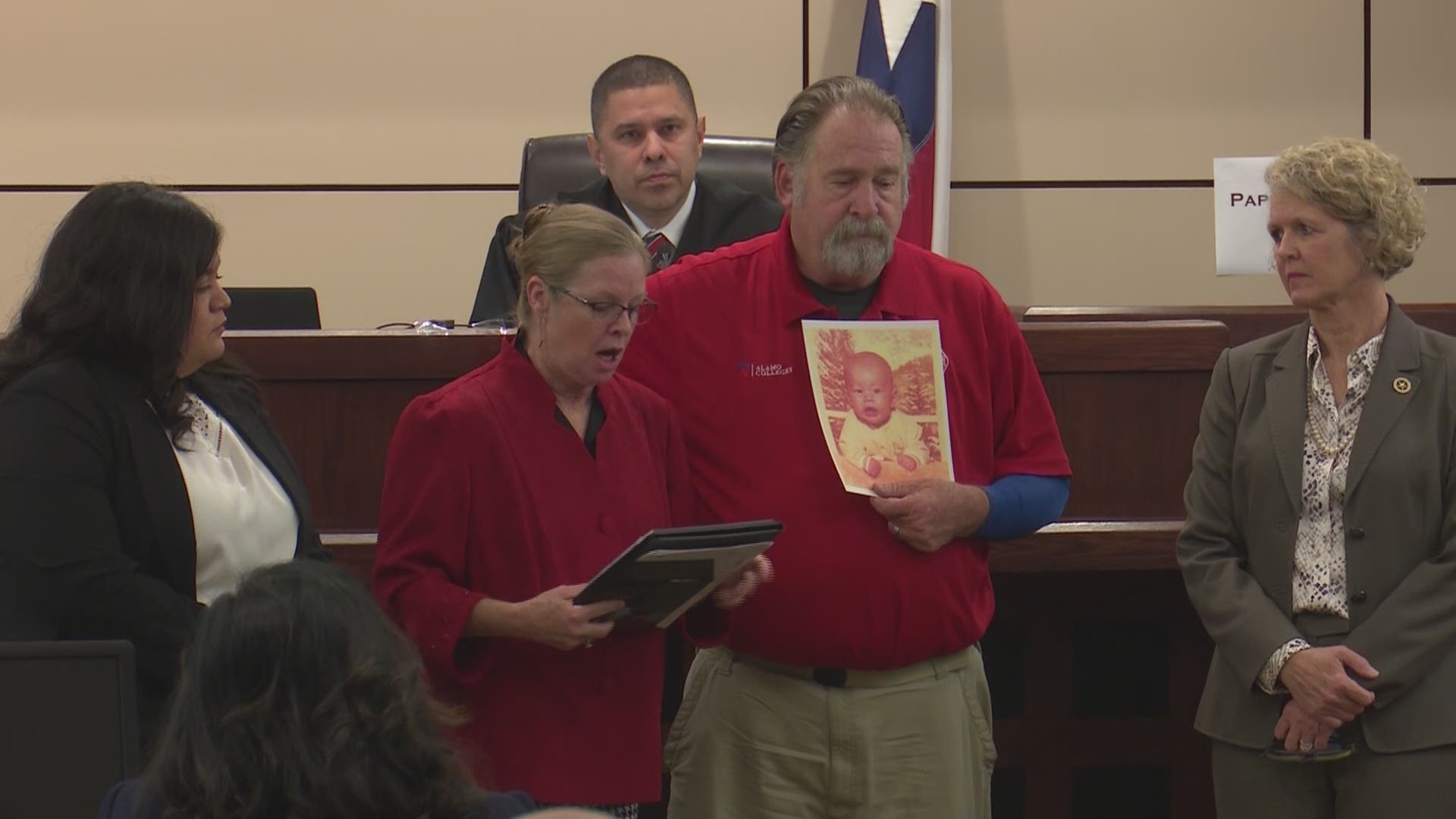

Chelsea died on Sept. 17, 1982. Petti said she immediately suspected something was wrong.

“When they brought Chelsea to us after she had passed, I was rocking her. They were letting us say goodbye to her. I said something right then, but then when we got in the car and we had to drive back home to Kerrville, I was telling my husband, 'You know, Reid, they did something to her.' He said 'No, Petti, something just had to be wrong. They're going to do an autopsy.' I said, 'I'm telling you, they did something to her.'”

As it turned out, Petti's instincts were correct. Genene Jones was later charged with and convicted of Chelsea's murder in 1984.

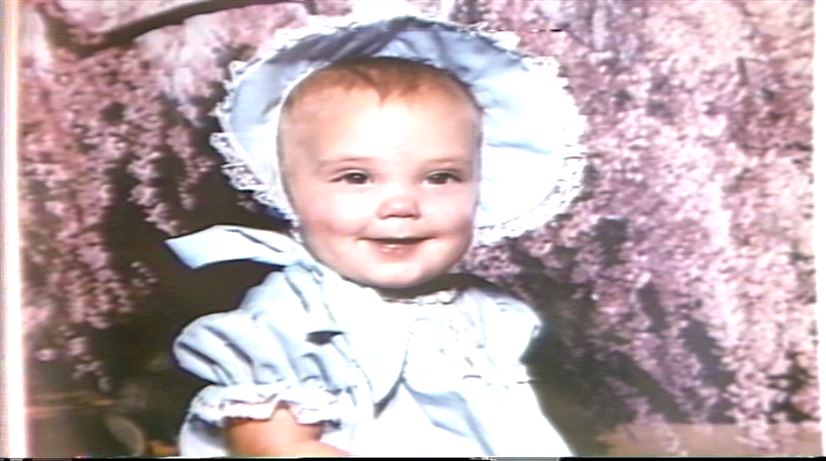

"I think the best thing about Chelsea was she was a pill. She was very strong-willed. She was little, but she was strong-willed," Petti said.

She said she also remembers her daughter's big, round eyes.

"They were almost a violet color. Those eyes, they kind of transcend you. After she was born, anywhere we ever went, it was always like, 'Oh my God, that child's eyes, they're gorgeous eyes. They're incredible."

"My sister told me this ... probably three or four years after, maybe it was after the trial was over. I was struggling, and she told me, 'Chelsea's job is done.' She said Chelsea wasn't meant to stay here for a long time. Her goal in this short life was to stop this person. Nobody else had been able to do it, but she did. Once she was done, it was time for her to go home."

"I was so mad at my sister. It hurt my feelings so bad. Now, looking back, it pretty much is what happened," Petti said.

She said she had to go through the seven steps of grieving after Chelsea's death.

"I got to the part where I was just damn mad. That's when I was able to say, 'Wait a minute.' It just became, this is what I have to do in life. I cannot let her out to hurt another baby."

"Some of the responses have been, 'That's just a mom not being able to let go or not being able to cope with the death of her child, living in the past.' That's not the case at all. I've had a great life. I had a great career, and my family is awesome.”

Petti later moved to the Houston area, about four hours east from where this all happened. Even after everything she went through, she went on to become a nurse.

"I was a nurse for 34 years. I wanted to be a nurse before any of this happened. [For a time] I didn't want any part of that, but I was told by a very wise person once that, you know, 'You're still letting [Jones] win by not being a nurse because of her. Why are you letting her do that?' So anyway, I went back to school, finished school and I loved it."

"I'm not one of these people that's going to work until they're 70. I'm going to retire and do volunteer work with kids. I'd also like to work with Alzheimer’s patients and spend time with my precious grandson. He's growing up way too fast. He is the love of my life," Petti said.

Next time on the VILE Podcast, we reach out to Dr. Holland about the past case and reaction to current charges against Jones.

KENS 5 is taking a look back at the history of the Genene Jones case and following new developments in the Vile podcast. This is an ongoing project. If you are connected to the case, and you would like to speak with us, email swelsh@kens5.com.

Stick with KENS5.com/Vile for the latest updates in our podcast series, plus photos, videos and audio recordings related to the story.